Main content

The Covid-19 pandemic is hitting low- and middle-income countries, where health care resources are already stretched. This article describes the spread of a Covid-19-like illness in M20 (a pseudonym), an isolated village without medical facilities in Indonesia. M20 is situated at an altitude of 6,700 feet in the central mountain range of Indonesia’s easternmost province, Papua. It is typically served on request by a small six to eight-seat aircraft, or reached by trekking on foot from other villages. The village consists of seven hamlets of two to six huts, separated by five to ten-minute walks. Villagers are closely related to inhabitants of other villages in the area, and visit each other often. In the villages of the Papuan highland, men and/or families sleep together in one hut, and children sleep with their mothers or families (sometimes up to 30 people in one hut). The closest neighbouring village to M20 is about 1.5 hour by foot, with people visiting multiple times a week. The actual population varies with these interactions and ranges from 150 to 200 people. M20’s gender distribution is estimated at 60% women, and 40% men, due to a combination of a higher life expectancy of women (66.8 years compared to 63.0 years for men) and men spending most of their time in towns.[1] Approximately half of the population is under twelve years of age. There are four to six matriarchs, and others are teenagers, young adults and adults in their thirties to fifties. Most men smoke, and most people live in huts with central fire pits, which are used throughout the day for cooking and during the evening and night for heating.[2] The closest government health centre is about three hours by foot, but trained health workers are typically absent, as is common in this region.[3] In M20, lay health workers hold daily clinics where they perform primary health care and dispense medication.

Methods

This account of an outbreak in a remote village in Papua is compiled from patient care records kept by lay healthcare workers in M20 during and after an outbreak, as well as medical doctors responding to online requests for help. We use a pseudonym to conceal the name of the village and protect its population; patient data were analysed anonymously. Symptoms of villagers seeking medical help were recorded by lay health workers, so initial mild symptoms were not systematically recorded. In most cases with infectious diseases the exact onset of infection is not clear. A major caveat is that polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for Covid-19 was not possible due to the lack of tests and test facilities. Our team repeatedly contacted the government health services, but PCR testing, or testing using reliable antibody tests, was not possible until the time of submission of this report (as of end of June). To collect information on Covid-19 symptoms of all villagers present during the outbreak, the lay medical workers also asked individuals who did not seek medical help about Covid-19 symptoms.

Epidemiologic timeline

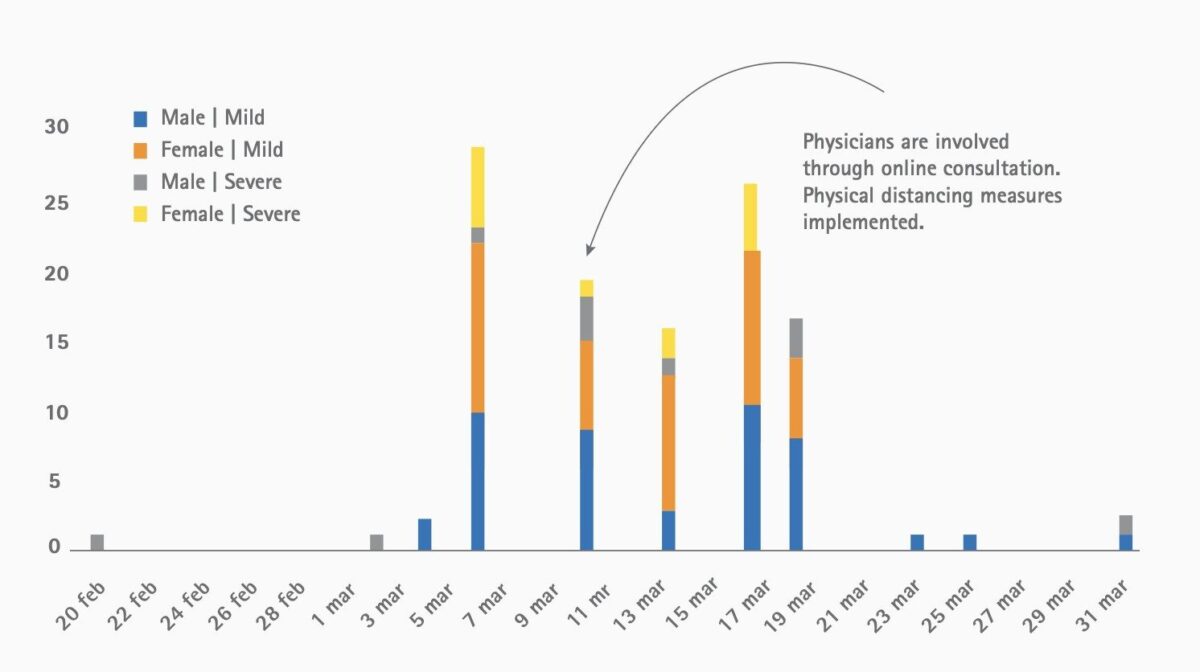

On 22 March 2020, the first case of confirmed Covid-19 was reported in Indonesia. However, suspected cases with links to Wuhan China were reported earlier in Jakarta in February 2020. On 20 February 2020, the first suspected Covid-19 patient reported in M20 for care with symptoms of fever, sore throat, cough and stomach complaints although at that time Indonesia had no official Covid-19 cases. Two weeks after the index case in M20, the number of cases rose steeply with 26 patients on one day (Figure 1). Covid-19 had become the top of the differential diagnosis list, as symptoms were in line with the WHO definition of Covid-19, and the index case had been in contact, prior to symptom onset, with a person who had travelled to Jakarta where probable Covid-19 cases were reported.[4] On 3 June 2020, Papua had 862 cases of Covid-19, while all of Indonesia counted 28,233 cases.[5]

Clinic records showed symptoms as summarized in Table 1. Table 2 presents the characteristics of the 101 suspected Covid-19 patients in M20. The illness started with several days of sore throat, followed by stomach complaints, and fever within 24 hours of stomach complaints. Fever and fatigue were constant, lasting 3-5 days. In severe cases (Table 2), fevers above 40°C often accompanied shortness of breath and chest pain, starting after day five of illness. Two villagers died after 48 hours of extreme shortness of breath. Both were male, over 40 years of age, and had underlying chronic illness (most likely chronic kidney disease). The lay healthcare workers treated patients with the limited resources available to them; those with moderate symptoms mainly received paracetamol, up to four times a day. Severely ill patients were given empiric amoxicillin treatment (49% of 101 patients) to prevent and/or treat a possible secondary bacterial pneumonia. Those with fevers over 40°C received a different antibiotic: amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (2% of the patients) or azithromycin (3% of the patients). The actual effect of antibiotics on recovery is not evident. Based upon advice early on in the worldwide epidemic to use chloroquine as a possible treatment for Covid-19, severely ill and high-risk patients (aged above 40), were given 150 mg chloroquine twice a day for seven days (14% of the patients).[6] Except for the two patients who died, all patients recovered. The effect of chloroquine and antibiotics on recovery is unknown.

As Figure 1 shows, the entire epidemic curve involved 101 patients (about half of the population of the village) over a period of four weeks. Informal questioning in the community revealed that only about ten villagers denied having had any symptoms yielding a presumptive infection rate of 90-95% of all residents. Of the twelve patients over age 40, five were severely sick (41%), and two died (17%). Approximately 50% had mild or no symptoms (Table 2). The median patient age is low (17 years), which might explain the unexpectedly low mortality of 1% given minimal health facilities and no mitigating measures.[7] The high proportion of females in the population may explain that more women (51.5% of the patients) were affected than men. Physical distancing measures were implemented, but their effect was unclear.

| AGE | MILD TO MODERATE SYMPTOMS | SEVERE SYMPTOMS | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALE | FEMALE | MALE | FEMALE | |||||

| 0-5 | 7 | 6.9% | 5 | 5.0% | 2 | 2.0% | 2 | 2.0% |

| 6-10 | 7 | 6.9% | 15 | 14.9% | 1 | 1.0% | 1 | 1.0% |

| 11-15 | 2 | 2.0% | 2 | 2.0% | 0 | 1 | 1.0% | |

| 16-20 | 8 | 7.9% | 1 | 1.0% | 0 | 0 | ||

| 21-25 | 2 | 2.0% | 2 | 2.0% | 1 | 1.0% | 0 | |

| 26-30 | 4 | 4.0% | 3 | 3.0% | 1 | 1.0% | 3 | 3.0% |

| 31-35 | 3 | 3.0% | 6 | 5.9% | 1 | 1.0% | 0 | |

| 36-40 | 3 | 3.0% | 5 | 5.0% | 1 | 1.0% | 0 | |

| 41-45 | 1 | 1.0% | 3 | 3.0% | 0 | 0 | ||

| 46-50 | 2 | 2.0% | 1 | 1.0% | 3 | 3.0% | 1 | 1.0% |

| 50+ | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1.0% | |||

| (median = 17) | ||||||||

| Total | 39 | 38.6% | 43 | 42.6% | 10 | 10.1% | 9 | 8.9% |

| SEVERE SYMPTOMS | APPROXIMATE PERCENTAGE OF PATIENTS REPORTING |

| Fever (either mild 37-38.5°C or high <38.5) | 80% |

| Shortness of breath | 70% |

| MILD SYMPTOMS | |

| Sore or dry throat | 90-95% adults. 60-70% children |

| Coughing (usually at night) | 80% |

| Fatigue | 90% |

| Lethargy (most of the children) | 80-90% children |

| Headache (late in the illness) | 60% |

| Muscle and joint pain | 10-20% |

| Diarrhoea | 20-30% |

| Vomiting | 10% |

Conclusion

This outbreak pattern of suspected SARS-CoV-2 in a village in the highlands of Papua (Indonesia) presents a unique report of the course of infection in an entire village population. The dense social structure of the village resulted in the rapid infection of 90-95% of the population within four weeks. Physical distancing and isolation measures were used, but probably not implemented optimally and too late. An effect on the illness course could not be observed.

The M20 population is young, which partially may explain the impact of the suspected Covid-19 outbreak and the relatively low case fatality rate (CFR) and overall death rate (1%), given the scarcity of direct health facilities and the difficulty of complying with mitigating measures like physical distancing. Treatment was provided in the form of chloroquine phosphate and azithromycin for severely ill and high-risk patients. However, no unequivocal conclusions regarding their efficacy can be drawn, something which requires further studies.[8]

References

- Badan Pusat Statistik Provinsi Papua [Internet]. Jayapura: Statistics Indonesia; 2020. Informasi terbaru; [cited 2020 Apr 23]. Available from: https://papua.bps.go.id

- Anderson B. Dying for nothing [Internet]. Inside Indonesia. 2014 Feb 11;115:1-16

- Vriend WH. Smoky fires: The merits of development co-operation for inculturation of health improvements [dissertation]. Amsterdam: Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; 2003.

- World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. 9 p. Report No.: 49

- World Health Organization Indonesia. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. 20 p. Report No.: 10

- Wang M, Cao R, Zhang L, et al. Remdesivir and chloroquine effectively inhibit the recently emerged novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in vitro. Cell Res. 2020 Mar;30(3):269-71

- Guan W, Ni Z, Hu Y, et al. Clinical characteristics of coronavirus disease 2019 in China. N Engl J Med. 2020 Apr 30;382(18):1708-20

- Wong YK, Yang J, He Y. Caution and clarity required in the use of chloroquine for COVID-19. Lancet Rheumatol. 2020 May; 2(5):e255