Main content

The emergence and spread of bacteria resistant to existing antibiotics is of growing global concern. Recent national and international actions have raised the political profile of Antimicrobial Resistance (AMR), such as; the adoption of the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Global Action Plan on AMR in May 2015, the White House Forum on Antibiotic Stewardship and the G7’s communiqué in June 2015, and the ongoing O’Neill Review on AMR in the United Kingdom. High rates of AMR have been noted in all regions of the globe. (1) At a minimum, the gradual loss of effective antibiotics will undermine our ability to fight infectious diseases. According to the O’Neill Review on AMR, up to 10 million people per year could die by 2050 due to resistance, compared to an estimated 700,000 deaths annually at present. (2) Furthermore, this figure does not capture the indirect impacts of AMR beyond the risk to mortality, such as the effects on animal health, food security and environmental risks. Antibiotic resistant bacteria spread through the environment and from individuals to populations and across countries as people and animals move around; the complexity of this issue is impacted by the broad and multi-sector drivers that are believed to be exacerbating resistance across the human, animal and agricultural/ environmental sectors. It is universally recognized that an effective response needs to simultaneously address both the development of new therapies and measures to slow the emergence of resistance. To be truly effective, these efforts have to recognize the considerable differences in the risks and challenges faced by governments and populations across the world. Low and Middle Income Countries (LMICs), where the majority of the world’s population live, not only pose a particular challenge in addressing antibiotic resistance but also will face a disproportionate burden. (3) It is in these countries that the issue of access and excess reveals the complexity of tackling AMR.

Access and excess: a particular challenge for LMICs

Access to antibiotics is a major concern in many LMICs, as seen with the high cost of the most recent and efficacious antibiotics or the unaffordability of appropriate doses and the increasing availability of counterfeit and low-quality antibiotics. (4) A common feature of health services in LMICs is the emergence of mixed or pluralistic health systems, where households use a vast range of public and private health care providers, many of whom are not controlled by national health authorities. These providers span a spectrum from medical specialists to informal providers, often combining both Western and local medical systems. There is evidence that these markets have widened the access to antibiotics and enabled people to treat many infections and reduce mortality. However, they also encourage excess use of antibiotics (self-medication, non-compliance, inappropriate use) and behaviour likely to encourage the emergence of resistance. (5)

The ways antibiotics are used are deeply embedded in meanings, networks, markets and norms. Some pervasive beliefs and meanings have been attached to antibiotics which influence how they are used. (6) Several factors influence deviations from what would be considered best practice for both providers and users, such as financial incentives, poverty, conflicting advice, peer influences, advertising pressures, perceived demands of patients, lack of education, inaccessibility to health care and diagnostic facilities, and ineffective law enforcement. (7)

One suggestion for addressing the challenge of antibiotic resistance would be to enact and enforce laws that restrict the right to prescribe antibiotics to licensed health workers. In the short-term, this may not be realistic in many pluralistic health systems, where people seek treatment from more informal providers as their only available access to medicines. This presents a hard choice to governments: denying many people access to life-saving drugs or turning a blind eye to nominally illegal practices which can exacerbate resistance. The alternative is to find ways to engage with these markets to improve antibiotic use. Tackling the access versus excess issue requires deeper understanding of the factors that influence providers and users and developing the role of government as regulator and steward of the health sector. (8)

A complex adaptive system

Ensuring universal appropriate access to antimicrobials is not only a critical part of realizing the right to health, it is necessary for mobilizing effective collective action against the development and spread of AMR. The issue to tackle is understanding how the flow of antibiotics should be controlled in a system. When patients need drug therapy, how do we ensure that the appropriate, effective, safe drug is prescribed for them, that it is available at the right time at a price they can afford, that it is dispensed correctly, and that it is taken in the right dose and for the right length of time. (9) This issue clearly involves a complex system of interacting components such as behaviours, financing, regulation and effective monitoring, whilst simultaneously involving a number of actors, organizational levels and possible outcomes. (10) Strategies to ensure access to and rational use of antibiotics will need to be designed with this complexity in mind.

There are indeed many strategic points of intervention; a realignment of incentives to providers, prescribers, dispensers, and users is important to encourage correct use of antimicrobial treatment. However, In order to be effective, these strategies must be sustainable, focus on reorientation of social norms, multidisciplinary, and multitier (pharmaceuticals, food and agriculture, human resources, financing, and information systems), linking science to practicality. These measures need to be informed by proven interventions built on effective surveillance systems. Although regulation is crucial to safeguard access to antibiotics, a transition towards such regulation needs governmental commitment and improvements in health systems that are not possible in many countries. Hence, antibiotic stewardship programs need to be adjusted to local conditions.

The wider context

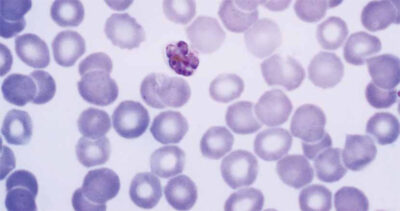

In LMICs, the spread of resistant bacteria is facilitated by poor hygiene, contaminated food, polluted water, overcrowding, direct cross-species transmission from animals, and increased susceptibility to infection because of malnutrition or chronic illness and/or infections causing immunosuppression such as HIV. Strategies to tackle access and excess also need to focus on these deeper facilitators of resistance. Similarly, the number of possible interventions may appear to be straightforward, but in fact they influence complex human, animal and environmental landscapes, especially when used in combination, and can result in many other effects, variable in different places and sometimes unwanted. Being cognizant of this wider context is paramount to creating a sustainable outcome, hence the calls to view resistance through the lens of a holistic, ecological, unified approach to health. (11)

The wider commitment

Bridging the divide between individual and collective action is key when it comes to tackling AMR. The implementation of a sustained effort to achieve system-wide changes in the use of current and future antibiotics requires informed and committed collaboration at both national and global levels. In May 2015, the WHO released a Global Action Plan on antibiotic resistance, but it remains to be seen whether effective global governance institutions can be created. The need for political commitments, frameworks and institutions at the national level is also recognized. (12) Countries that have implemented comprehensive national strategies and contextualized, targeted and prioritized approaches have been the most successful in controlling resistance. (13) However, these programs need time and patience to be set up and need to be backed by visionary governments with adequate funding. In resource-poor countries, there has been much less progress. The bottlenecks for implementing programs are largely a result of insufficient leadership, commitment, and funding. (14) Involving the key players, such as global health donors, pharmaceutical companies, technical agencies, NGOs, governments, patients, and physicians, in partnership arrangements while protecting the interests of the relatively poor and powerless will be key to creating sustainable approaches to tackle AMR.

Outlook

To ensure that a global strategy will effectively address AMR, measures need to tackle the appropriate use of antibiotics whilst ensuring just and sustainable access to antibiotics in LMICs. Finding the right balance between access and excess will require knowledge of the wider complex system of interacting components including behaviour, financing, and regulation and monitoring at the various organizational levels and in the human, animal and environmental landscapes involved. Solutions need to focus on multifaceted and multilevel interventions supported by active participation of a variety of actors that define local barriers and beliefs, which can vary widely between cultures, countries, and regions. A single approach is unlikely to suit all settings; sustainable change will require mutually reinforcing strategies at local, national and global levels.

References

- WHO. Antimicrobial Resistance: Global Report on Surveillance. Available at: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/112642/1/9789241564748_eng.pdf?ua=1 [Accessed 17 August 2015].

- O’Neil J. Antimicrobial Resistance: Tackling a crisis for the health and wealth of nations. Available at: review http://amr-review.org/sites/default/files/AMR%20Review%20Paper%20-%20Tackling%20a%20crisis%20for%20the%20health%20and%20wealth%20of%20nations_1.pdf [Accessed 19th August 2015].

- Okeke I. Poverty and root causes of resistance in developing countries. In Sosa A, Byarugabal D, Amabile-Cuevas C, Hsueh P, Kariuki S and Okeke N. (eds.) Antimicrobial resistance in developing countries. Springer, New York/ Dordrecht/Heidelberg/London; 2010. p. 27-35.

- Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, et al. Antibiotic resistance – the need for global solutions. The Lancet. 2013; 13: 1057-1098.

- Peters D, Bloom G. Developing world: bring order to unregulated health markets. Nature. 2012; 487: 163-165.

- Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, Zaidi A, et al. Dynamic Sustainabilities: Technology, Environment, Social Justice. London: Routledge (Earthscan); 2011.

- Haak H. Improving antibiotic use in low-income countries: an overview of evidence on determinants. Social Science and Medicine. 2003; 57:733-744.

- Ahmed S, Evans T, Standing H, Mahmud S. Harnessing Pluralism for Better Health in Bangladesh. The Lancet. 2013; 382.9906: 1746-1755.

- Tomson G, Vlad I. The need to look at antibiotic resistance from a health systems perspective. Uppsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 2013; 119: 117-124.

- Grundmann H. Towards a global antibiotic resistance surveillance system: a primer for a roadmap. Uppsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 2014; 119(2): 87-95.

- Laxminarayan R, Duse A, Wattal C, et al. Antibiotic resistance – the need for global solutions. The Lancet. 2013; 13: 1057-1098

- Stålsby Lundborg C, Tamhankar AJ. Understanding and changing human behaviour – antibiotic mainstreaming as an approach to facilitate modification of provider and consumer behaviour. Uppsala Journal of Medical Sciences. 2014; 119: 125-133.

- WHO. Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available at: http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA68/A68_20-en.pdf [Accessed 16th August 2015].

- Daulaire N, Bang A, Tomson G, et al. Universal access to effective antibiotics is essential for tackling antibiotic resistance. The Journal of Law, Medicine and Ethics. 2015; 43(3): 17-21.