Main content

Tropical cyclone Idai hit three provinces in northern Mozambique in early March 2019. One week later, the WHO Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network (GOARN) [1] issued a request for assistance to its partners around the world to identify field epidemiologists and other technical specialists for immediate deployment to Mozambique. The tasks outlined for field epidemiologists included: leading the development of an information repository on core public health indicators (e.g. crude and under-five mortality rates, prevalence of malnutrition, vaccination coverage) for Mozambique; working with other team members to analyse outbreak intelligence in real-time for epidemic forecasting and detection; and conducting health needs assessments. In addition, field epidemiologists were needed to collate and verify data on reported outbreaks, including rumours, received from multiple sources, and assess the efficiency of the verification mechanisms. They were expected to analyse reported incidents and determine trends and distribution patterns. Immediately after the cyclone, residents of the Mozambique Field Epidemiology and Laboratory Training Program [2] were deployed to Beira province for surveillance and early outbreak detection, gathering information to support other health professionals, ‘acute watery diarrhoea’ surveillance, case finding, and monitoring and communication. On 27 March 2019, one day after the GOARN request for assistance to international partners, the first cases of cholera were confirmed in Mozambique.[3]

Source: https://www.tephinet.org/training-programs

What is field epidemiology?

Field epidemiology is the practical application of epidemiologic methods and tools to public health problems. It can mean working in difficult situations with incomplete information, and limited resources, but the focus is on timely intervention and using available data to support public health action.

Disease surveillance

An important component of field epidemiology involves working with surveillance systems for detection of disease outbreaks, monitoring disease trends, identifying risk groups, and evaluating interventions. While most countries have national surveillance systems to monitor a set of notifiable diseases, humanitarian response can necessitate rapid implementation of surveillance in challenging conditions. Early warning syndromic surveillance systems can be set up in order to promptly detect outbreaks that may occur, given the local circumstances. This could include surveillance for acute watery diarrhoea to detect cholera following floods, or surveillance for clusters of fever and rash to detect vaccine-preventable diseases in crowded refugee settings, such as the crowded Rohingya camps in Bangladesh.[4-6]

Outbreak investigations

The main objective of an outbreak investigation is to identify the cause of the outbreak and to implement control measures to prevent the occurrence of more cases. In a foodborne outbreak, it is critical to identify the source in order to prevent further illness and to intervene in the food chain or food service setting to prevent similar outbreaks in future. When a sudden increase of a vaccine-preventable disease is observed in an area with high vaccine coverage, a key question is whether the cause is vaccine failure or a failure to vaccinate. In the 2014/2015 Ebola outbreak in West Africa, field epidemiologist played an important role in detecting and describing the geographical spread of the outbreak in the affected countries.[7]

Operational research

Another core activity in field epidemiology is operational research, which can have various objectives such as evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention or the performance of a surveillance system or the distribution of risk factors for a communicable disease, with the aim of informing public health policy and programme resource decisions.

Field epidemiology training programmes (FETPS)

Field epidemiology training programmes are a practical solution to building skills among public health professionals in the basic concepts of outbreak investigations, disease surveillance, and the evaluation of public health interventions, in order to strengthen the local, national, and international public health infrastructure.

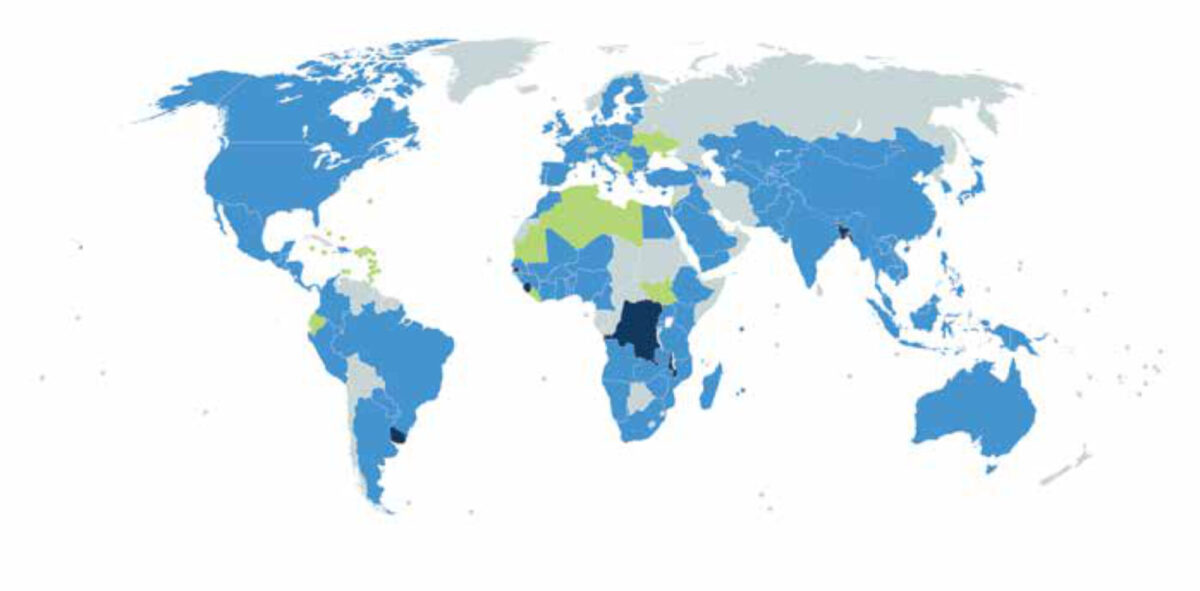

The first FETP was the Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS), which started in 1951 at the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (USCDC).[8] Since then, more than 70 programmes have been established in over 100 countries (Fig. 1). Many national and regional FETPs now incorporate a laboratory and/or veterinary track to encourage collaboration, build capacity through the entire health sector, and strengthen laboratory networks.

In 1995, the European Commission funded European Programme for Intervention Epidemiology Training (EPIET) welcomed its first cohort of fellows to a two-year competency-based training scheme. The Fellowship Programme is now managed by the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and comprises two paths, EPIET for field epidemiology and EUPHEM for public health microbiology.[9] During the programme, while working in public health agencies across Europe, fellows learn to apply epidemiological or microbiological methods to provide evidence to guide public health interventions for communicable disease prevention and control.

Field epidemiology networks are important. Having a network of professionals that know each other, speak the same ‘language’ (professionally), and can easily access each other’s expertise represents an important resource for global public health (see Table 1). TEPHINET is a worldwide professional network of FETPs that provides a global platform for scientific and practical information exchange, and accreditation of newly established FETPs.[10]

| Textbooks |

|

| Epidemiologic Case studies |

|

Other networks include the African Field Epidemiology Training Network (AFENET), the South Asia Field Epidemiology Training Network (SAFETYNET), the Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Network (EMPHNET), the South American Field Epidemiology Network (REDSUR), and the European EPIET Alumni Network (EAN).[11-14]

Curriculum

FETP trainees, residents, or fellows take part in a two-year fulltime FETP programme. The training is a learning-by-doing, which means working at a public health agency on a national or regional level. The curriculum is based on the target competencies for public health professionals, as defined by national or regional bodies.[15-17] The classroom-based training supports fellows in putting their learning into practice and demonstrating their ‘competency’. FETP requirements vary but can include: investigating an outbreak; designing, evaluating or coordinating a surveillance system; designing and implementing an applied epidemiological field study; producing oral and written scientific communication; and developing and delivering training to others. Field epidemiologists are often required to build and work with ad hoc teams during field investigations, and to train team members for the tasks required for the investigation. In addition to their technical learning, FETP students develop excellent communication skills and competencies in teaching.

Frontline (or short) FETPS

The 2013-2015 West Africa Ebola epidemic, which primarily affected Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, demonstrated a lack of field epidemiologists at local levels, where detection and response could have happened earlier in the outbreak. In 2015, the USCDC launched the so-called FETP-Frontline, a 3-month field training programme targeting local Ministry of Health staff in 24 countries to strengthen local public health capacity.[18] The programme enhances global health security by training local public health staff to improve surveillance quality in their jurisdictions, as part of a strategy to help countries to detect, respond to, and contain public health emergencies more rapidly.

FETP-Frontline participants have used their training to identify gaps and promote change in the public health systems in which they work. For example, Guinea-Bissau FETP-Frontline participants made policy recommendations to improve the way in which dog bites are tracked, in terms of follow-up with rabies testing, and to improve data confidentiality and protection for patients. In The Gambia, under the resident advisor’s guidance, members of the first cohort came up with recommendations for improving the surveillance system such as: appointing district surveillance officers where there were none previously, training new staff in basic epidemiology, and including private health clinics in the national surveillance strategy. In Côte d’Ivoire, Senegal, and Togo, where training has included participants from both the human and animal health sectors, trainees have worked together to conduct coordinated joint investigations to combat rabies.

Conclusion

People working in health programmes or facilities in low or middle-income countries can suddenly find themselves on the frontline of an epidemic. Every healthcare worker in these settings can benefit from familiarization with some basic principles of field epidemiology in order to enhance readiness to deal with a public health crisis. There is a lot of free online training material available (see Table 1) to review and practice concepts of field epidemiology.

Ongoing capacity building in the core field epidemiology functions of disease surveillance and outbreak response is essential in an era with ongoing threats and potential emerging infections. Investing in training local health experts in field epidemiology will therefore contribute to a sustainable increase in the much-needed public health global workforce.

References

- World Health Organization, Global Outbreak Alert and Response Network. www.who.int/ihr/alert_and_response/outbreak-network/en

- Baltazar CS, Taibo C, Sacarlal J, et al. Mozambique field epidemiology and laboratory training program: a pathway for strengthening human resources in applied epidemiology. Pan Afr Med J. 2017 Jul 31; 27:233. doi: 10.11604/pamj.2017.27.233.13183.

- Mozambique: Cyclone Idai & Floods Flash Update No. 11, 27 March 2019. Report from UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs. https://reliefweb.int/report/mozambique/mozambique-cyclone-idai-floods-flash-update-no-11-27-march-2019

- Early Warning, Alert and Response System (EWARS). World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/emergencies/kits/ewars/en/

- Karo B, Haskew C, Khan AS, et al. World Health Organization Early Warning, Alert and Response System in the Rohingya Crisis, Bangladesh, 2017-2018. Emerg Infect Dis. 2018 Nov; 24(11):2074-2076. doi: 10.3201/eid2411.181237. Epub 2018 Nov 17.

- Hussain-Alkhateeb L, Kroeger A, Olliaro P, et al. Early warning and response system (EWARS) for dengue outbreaks: Recent advancements towards widespread applications in critical settings. PLoS One 2018 May 4; 13(5):20196811. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0196811.

- Lubogo M, Donewell B, Godbless L, et al. Ebola virus disease outbreak; the role of field epidemiology training programme in the fight against the epidemic, Liberia, 2014. Pan Afr Med J. 2015;22(Suppl 1):5. doi: 10.11694/pamj.supp.2015.22.1.6053

- Epidemic Intelligence Service. US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/eis/index.html

- Fellowship programme: EPIET/EUPHEM. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/epiet-euphem

- Training Programs in Epidemiology and Public Health Interventions Network (TEPHINET). https://www.tephinet.org

- The African Field Epidemiology Training Network (AFENET). http://afenet.net/

- The South Asia Field Epidemiology Training Network (SAFETYNET). https://www.safetynet-web.org/

- The Eastern Mediterranean Public Health Network (EMPHNET). http://emphnet.net/

- EPIET Alumni Network. https://epietalumni.net

- Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/public-health-practice/skills-online/core-competencies-public-health-canada.html

- CSTE Applied epidemiology Core Competencies. https://www.cste.org/page/CoreCompetencies

- Core competencies of ECDC training programmes and instructional design. https://ecdc.europa.eu/en/training-programmes/training-public-health-professionals/core-competencies

- André AM, Lopez A, Perkins S, et al. Frontline Field Epidemiology Training Programs as a Strategy to Improve Disease Surveillance and Response. Emerg Infect Dis. 2017 Dec; 23(13). doi: 10.3201/eid2313.170803.