Main content

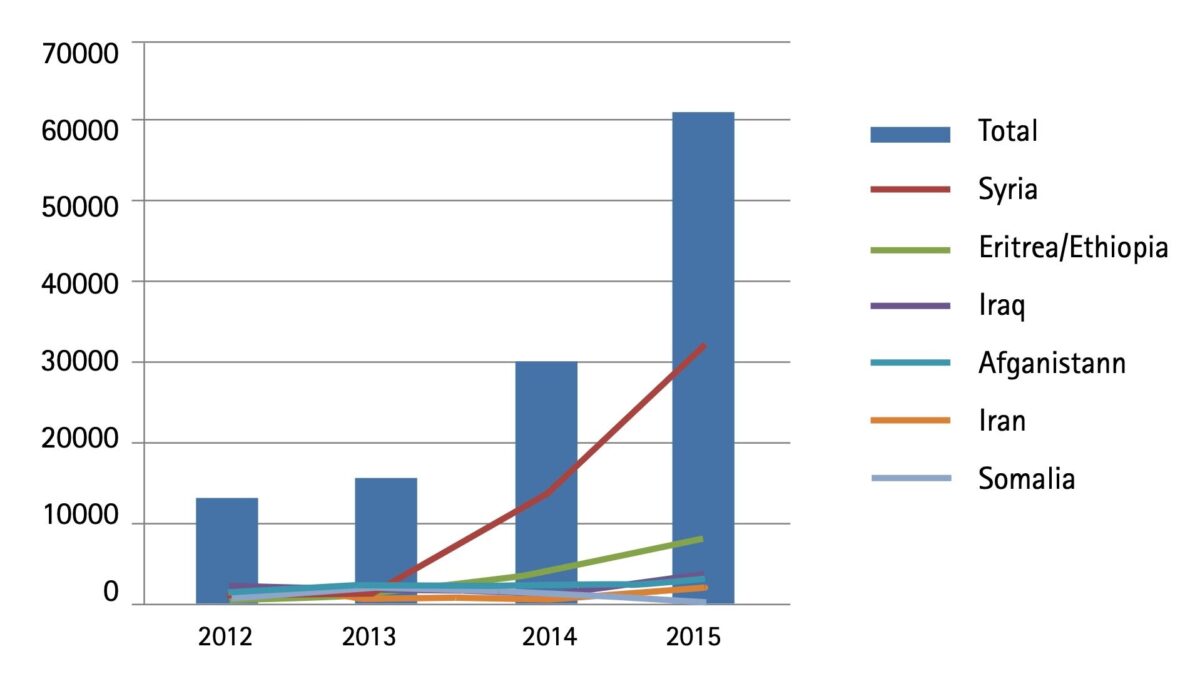

In 2015, the influx of refugees into Europe more than tripled, with over a million refugees arriving in 2015. Syria, Iraq and Afghanistan account for approximately 80% of the refugees. Poverty, human rights abuses, and deteriorating security are also prompting people to leave countries such as Eritrea, Somalia, Morocco, Iran and Pakistan. In 2015, the number of asylum applications in the Netherlands was twice as high compared to the previous year (Figure 1). The increase in the Netherlands was mainly attributable to the increase of Syrian asylum seekers. Since 2012, notifiable infectious diseases in asylum seekers in the Netherlands have been monitored using Osiris, the Dutch notifiable infectious diseases database. Data on notifiable infectious diseases are collected by the municipal health services.

Overview of notifiable infectious diseases

In this article, we provide an overview of notifiable infectious diseases reported in asylum seekers living in accommodation provided by the Central Agency for the Reception of Asylum Seekers (COA) in the Netherlands. Table 1 shows the number of notifications of infectious diseases in this group by year of disease onset in the period 2012-2015. When interpreting the number of notifications, the increase in the number of asylum seekers arriving in the Netherlands has to be taken into account. We will discuss the most frequently reported infectious diseases in asylum seekers: tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis B and malaria.

We have used the occupancy figures at the COA to calculate the incidence of notifications of notifiable diseases. For the occupancy per year, we calculated the mean of the occupancy on the first of each month from January of the given year up until January of the year after.

| Group** | Disease | 2012*** (%) | 2013 (%) | 2014 (%) | 2015 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group A1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Group B12 | Tuberculosis5 | N/A | N/A | 79 (9.2) | 106 (11.8) |

| Group B23 | Hepatitis A | 0 | 2 (< 1.0) | 2 (1.9) | 9 (11.4) |

| Hepatitis B Acute | 1 (< 1.0) | 3 (2.1) | 2 (1.4) | 1 (< 1.0) | |

| Hepatitis B Chronic | 61 (4.6) | 69 (6.1) | 91 (8.5) | 106 (10.6) | |

| Invasive group A streptococcal disease | 0 | 0 | 2 (1.3) | 1 (< 1.0) | |

| Measles | 0 | 1 (< 1.0) | 0 | 1 (14.3) | |

| Paratyphi C | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (25.0) | |

| Pertussis | 49 (< 1.0) | 8 (< 1.0) | 19 (< 1.0) | 8 (< 1.0) | |

| STEC/enterohemorragic E.coli infection | 2 (< 1.0) | 0 | 1 (< 1.0) | 1 (< 1.0) | |

| Shigellosis | 0 | 0 | 3 (< 1.0) | 4 (< 1.0) | |

| Typhoid fever | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 (11.8) | |

| Brucellosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (11.1) | |

| Group C4 | Hantavirus infection | 0 | 1 (2.7) | 0 | 0 |

| Invasive pneumococcal disease (in children 5 years or younger) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.3) | |

| Legionellosis | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (< 1.0) | |

| Malaria | 4 (2.0) | 6 (4.2) | 106 (37.2) | 126 (36.3) | |

| Meningococcal disease | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 | |

| Mumps | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.1) | |

| Psittacosis | 0 | 0 | 1 (2.4) | 0 |

*The Table was sourced from the Dutch notifiable infectious diseases database ‘Osiris’ on 02 May 2016. The number of reported cases is subject to change as cases may be entered at a later date or retracted on further investigation. The longer the time between the period of interest and the date this Table was sourced, the more likely it is that the data are complete and the less likely they are to change.

**Notifiable infectious diseases in the Netherlands are grouped depending on the legal measures that may be imposed.

***It was not until 2012 that the question ‘if a person is living in an asylum center’ was added to Osiris. Therefore, it could be that notifications in 2012 are an under-reporting of the actual number of disease notifications in asylum seekers in 2012.

1. 0 cases for MERS-CoV, polio, SARS, smallpox and viral hemorrhagic fever.

2. 0 cases for diphtheria, human infection with zoonotic influenza virus, plague and rabies.

3. 0 cases for cholera, clusters of foodborne infection, hepatitis c acute, paratyphi a, paratyphi b and rubella.

4. 0 cases for anthrax, botulism, chikungunya, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease -variant, dengue, invasive hemophilus influenza type b infection, leptospirosis, listeriosis, MRSA-infection (clusters outside hospitals), q fever, tetanus, trichinosis, West Nile virus and yellow fever.

5. It was not until 2014 that the question ‘if the patient is living in an asylum center’ was added to the tuberculosis questionnaire.

N/A: not available

Tuberculosis

In 2015, 106 cases of tuberculosis (TB) in asylum seekers were notified, accounting for 12% of all TB notifications in the Netherlands. This is a slight increase compared to 2014 (Table 1). The largest group accounting for TB cases in asylum seekers originated from Eritrea/Ethiopia (Table 2). In the last two years, most asylum seekers originated from Syria and among them TB is relatively uncommon. The incidence of TB notifications in asylum seekers in 2014 and 2015 was 0.4 per 100 persons. In 2015, the incidence of TB notifications in asylum seekers from Eritrea/Ethiopia and Somalia decreased compared to 2014 (Table 2). In 2015, cases of TB were only reported in asylum seekers in the age groups 5-17 and 18-50 years. The incidence of TB notifications per 100 asylum seekers in those age groups decreased slightly compared to 2014 (Table 3). In 2015, 25% of asylum seekers with TB were diagnosed with infectious pulmonary TB against 16% the previous year. Between 2010-2015, the proportion of infectious pulmonary TB of the total number of TB patients in the Netherlands varied between 23% and 26%. Asylum seekers and immigrants from countries with an estimated WHO-incidence of more than 200 per 100,000 populations and from specified other high-risk countries, such as Eritrea, are invited for a six monthly follow-up CXR screening for a period of two years [3].

Chronic hepatitis B

In 2015, 106 chronic hepatitis B cases in asylum seekers were notified, accounting for 11% of all notified chronic hepatitis B cases in the Netherlands. This is an increase compared to 2014, with 9% of all cases (Table 1).

Over the last two years, most notified chronic hepatitis B cases originated from Syria and Eritrea (Table 4). In the years prior to that, most cases originated from Somalia, Syria and Sierra Leone. The incidence of chronic hepatitis B notifications in asylum seekers staying in 2015 was 0.5 per 100 persons, which is comparable to the years prior to that. The incidence of chronic hepatitis B notifications in asylum seekers from Sierra Leone has decreased over the past few years. In 2015, a slight increase was observed in the incidence of chronic hepatitis B notifications in asylum seekers from Eritrea/Ethiopia and Somalia compared to 2014 (Table 4). In 2015 and 2014, the incidence of chronic hepatitis B notifications per 100 asylum seekers was highest in the age group 18-50 years (Table 5). In 2015 and 2014, the incidence of chronic hepatitis B notifications in asylum seekers in the age group 5-17 was substantially lower than in 2013.

Asylum seekers in the Netherlands are not systematically screened for chronic hepatitis B. The incidence of acute hepatitis B infection in the general population in the Netherlands has been declining for more than 10 years, and has been below 1 per 100,000 since 2013. This suggests that the increasing influx of refugees from higher prevalence countries is not associated with an increasing transmission of hepatitis B within the Dutch population.

| 2014 | 2015 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of birth | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons |

| Eritrea/Ethiopia | 45 | 2,957 | 1.5 | 68 | 5,205 | 1.3 |

| Syria | 2 | 5,398 | 0.0 | 9 | 12,861 | 0.1 |

| Afghanistan | 0 | 1,321 | 0.0 | 7 | 1,399 | 0.5 |

| Somalia | 14 | 1,568 | 0.9 | 7 | 853 | 0.8 |

| Other | 18 | 8,308 | 0.2 | 15 | 9,680 | 0.2 |

| Total | 79 | 19,552 | 0.4 | 106 | 29,998 | 0.4 |

| 2014 | 2015 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons |

| 0-4 | 1 | 1,821 | 0.1 | 0 | 2,337 | 0.0 |

| 5-17 | 15 | 4,115 | 0.4 | 21 | 6,037 | 0.3 |

| 18-50 | 63 | 12,530 | 0.5 | 85 | 20,132 | 0.4 |

| 50+ | 0 | 1,087 | 0.0 | 0 | 1,492 | 0.0 |

| Total | 79 | 19,552 | 0.4 | 106 | 29,998 | 0.4 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of birth | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons |

| Syria | 6 | 517 | 1.2 | 7 | 1,089 | 0.6 | 14 | 5,398 | 0.3 | 26 | 12,861 | 0.2 |

| Eritrea/Ethiopia | 2 | 498 | 0.4 | 6 | 721 | 0.8 | 11 | 2,957 | 0.4 | 24 | 5,205 | 0.5 |

| Somalia | 6 | 1,764 | 0.3 | 11 | 1,840 | 0.6 | 3 | 1,568 | 0.2 | 4 | 853 | 0.5 |

| Sierra Leone | 7 | 242 | 2.9 | 6 | 250 | 2.4 | 3 | 277 | 1.1 | 2 | 257 | 0.8 |

| Afghanistan | 6 | 2,244 | 0.3 | 3 | 1,868 | 0.2 | 2 | 1,321 | 0.2 | 5 | 1,399 | 0.4 |

| Unknown/Other | 34 | 9,124 | 0.4 | 36 | 8,937 | 0.4 | 57 | 8,031 | 0.7 | 45 | 9,423 | 0.5 |

| Total | 61 | 14,389 | 0.4 | 69 | 14,705 | 0.5 | 91 | 19,552 | 0.5 | 106 | 29,998 | 0.4 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons |

| 0-4 | 0 | 1,560 | 0.0 | 0 | 1,593 | 0.0 | 1 | 1,821 | 0.1 | 0 | 2,337 | 0.0 |

| 5-17 | 13 | 2,816 | 0.5 | 18 | 3,281 | 0.5 | 7 | 4,115 | 0.2 | 5 | 6,037 | 0.1 |

| 18-50 | 46 | 9,071 | 0.5 | 50 | 8,910 | 0.6 | 75 | 12,530 | 0.6 | 98 | 20,132 | 0.5 |

| 50+ | 2 | 942 | 0.2 | 1 | 921 | 0.1 | 8 | 1,087 | 0.7 | 3 | 1,492 | 0.2 |

| Total | 61 | 14,389 | 0.4 | 69 | 14,705 | 0.5 | 91 | 19,552 | 0.5 | 106 | 29,998 | 0.4 |

Malaria

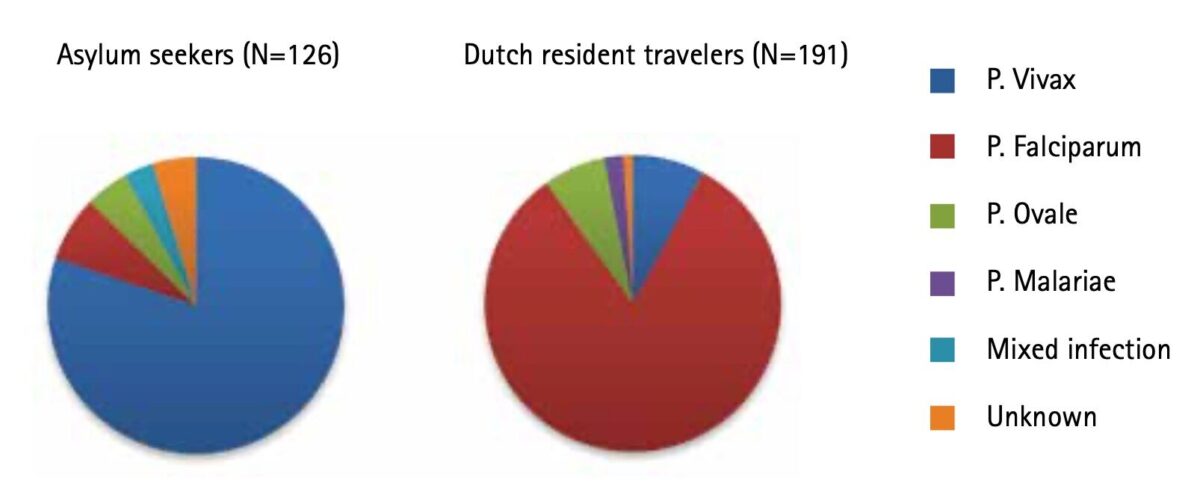

Over the last 2 years, an increase in malaria cases has been observed in the Netherlands. This increase is largely explained by the increase of malaria cases in asylum seekers. In 2015, 126 malaria cases in asylum seekers were notified, accounting for 36% of all malaria cases in the Netherlands (Table 1). In the years prior to that, only a few malaria cases were reported in asylum seekers. In 2014 and 2015, over 90% of asylum seekers with malaria were born in Eritrea or Ethiopia (Table 6). The total incidence of malaria notifications in asylum seekers slightly decreased in 2015. This decrease was also observed in the incidence of malaria notifications in asylum seekers from Eritrea/Ethiopia (Table 6). In 2015, the incidence of malaria notifications was highest in the age groups 5-17 and 18-50 (Table 7). This is comparable to previous years.

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country of birth | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons |

| Eritrea/Ethiopia | 1 | 498 | 0.2 | 4 | 721 | 0.6 | 96 | 2,957 | 3.2 | 118 | 5,205 | 2.3 |

| Unknown/Other | 3 | 13,891 | 0.0 | 2 | 13,984 | 0.0 | 10 | 16,595 | 0.1 | 8 | 24,793 | 0.0 |

| Total | 4 | 14,389 | 0.0 | 6 | 14,705 | 0.0 | 106 | 19,552 | 0.5 | 126 | 29,998 | 0.4 |

| 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age groups | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons | Notifications | Occupancy COA | Notifications per 100 persons |

| 0-4 | 0 | 1,560 | 0.0 | 0 | 1,593 | 0.0 | 0 | 1,821 | 0.0 | 0 | 2,337 | 0.0 |

| 5-17 | 0 | 2,816 | 0.0 | 0 | 3,281 | 0.0 | 39 | 4,115 | 0.9 | 36 | 6,037 | 0.6 |

| 18-50 | 4 | 9,071 | 0.0 | 6 | 8,910 | 0.1 | 67 | 12,530 | 0.5 | 89 | 20,132 | 0.4 |

| 50+ | 0 | 942 | 0.0 | 0 | 921 | 0.0 | 0 | 1,087 | 0.0 | 1 | 1,492 | 0.1 |

| Total | 4 | 14,389 | 0.0 | 6 | 14,705 | 0.0 | 106 | 19,552 | 0.5 | 126 | 29,998 | 0.4 |

The parasite mostly responsible for the malaria cases in asylum seekers was Plasmodium vivax. In Dutch resident travellers (including work related travel), P. falciparum is the parasite that most often causes malaria (Figure 2).

Drawbacks

The surveillance of notifiable infectious diseases in asylum seekers as described in this article is based on disease notifications of asylum seekers living in asylum centres and collective reception centres of COA. Infectious diseases data on asylum seekers not living in COA centres (e.g. municipal emergency shelters) and refugees with a residence permit living in the community (including family reunification) cannot be obtained as such from the surveillance system. Furthermore, the surveillance of notifiable infectious diseases does not provide insight in the occurrence of infectious diseases in asylum seekers that are not notifiable, e.g. scabies. There are indications that non-notifiable infectious diseases constitute the main disease burden in asylum seekers. The RIVM-CIb, in collaboration with NIVEL, the Asylum Seekers Health Centre (GCA) and others, has therefore initiated a pilot primary care syndromic surveillance project for non-notifiable infectious diseases in asylum seekers.

Conclusions

The influx of asylum seekers into the Netherlands doubled in 2015. Even though the large influx of asylum seekers was mainly attributed to the increase of Syrian asylum seekers, most infectious diseases reported in asylum seekers are in people originating from the Horn of Africa. The most frequently reported notifiable infectious diseases in asylum seekers in the Netherlands were tuberculosis, chronic hepatitis B and malaria. The incidence of notified infectious diseases varies by country of origin, and depends also on the countries visited en route and conditions there. There is a low risk of transmission of infectious diseases from asylum seekers to the Dutch population. [4]

Note

This article will also appear in Dutch in a special issue on asylum seekers of the RIVM-publication Infectieziekten Bulletin, November 2016, www.rivm.nl/Onderwerpen/I/Infectieziekten_Bulletin

References

- COA. Grenzen – Jaarverslag 2015. COA, 2016.

- IND. Asieltrends 2016 [cited 2016 6 June]. Available from: https://ind.nl/organisatie/jaarresultaten-rapportages/rapportages/Asieltrends/Paginas/default.aspx.

- de Vries G, Gerritsen RF, van Burg JL, Erkens CG, van Hest NA, Schimmel HJ, et al. [Tuberculosis among asylum-seekers in the Netherlands: a descriptive study among the two largest groups of asylum-seekers]. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde. 2015;160(0):D51.

- ECDC. Communicable disease risks associated with the movement of refugees in Europe during the winter season. Rapid Risk Assessment. ECDC, 2015.