Migrant Health 2

Editorial

Health of people on the move

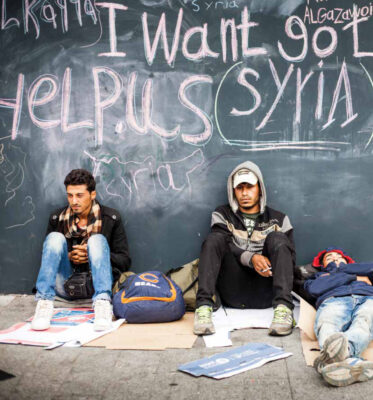

“A refugee used to be a person driven to seek refuge because of some act committed or some opinion held. Well, it is true we had to seek refuge, but we committed no acts and most of us never dreamt of having any radical opinions”. In his article, Tammam Aloudat from MSF Switzerland quotes the philosopher Hannah Arendt in her article on refugees in 1943. Today, millions of people are again seeking refuge. According to UNHCR, nearly 34,000 people are forcibly displaced each day as a result of conflict or persecution.(1) An unprecedented 65.3 million people around the world have been forced from home. That means that 1 in every 113 people on earth is either an asylum-seeker, internally displaced, or a refugee. The vast majority of the world’s refugees – nine out of ten – are hosted in countries close to their home country, led by Turkey, Pakistan, Lebanon and Jordan. Some 6% are hosted in Europe. These are staggering numbers, with staggering stories behind the numbers. The theme of this MTb is migrant health. Interestingly enough, as Muijsenbergh points out in her article, most migrants start their journey in relatively good health – ironically called ‘the healthy migrant effect’. You simply have to be healthy to travel the long and windy roads and seas to get here. The sad reality is that their health status gets worse along the way. It’s often a very, very long way, and some travel up to 100 days according to an MSF study among Eritrean refugees in Calais. Not all migrants have a healthy start though, as many leave situations of poverty or failing health services. The sexual and reproductive health rights of people ‘on the move’ are often violated, not only while on the move but already in their countries of origin, as Okur illustrates in her article. Ploem addresses gender bias in humanitarian aid and how we can avoid falling into the gender-stereotyping trap. Once safe ground is reached, the health services can do their work. Two articles discuss the health status of asylum seekers, with Nijsten providing a general overview of the common diseases they present and Curvers et al. introducing a study on infectious diseases, a study which potentially can form the basis for a vaccination policy for adult asylum seekers. Aarts et al. first take us on a historical journey to the early days of the 20th century when millions of Europeans migrated to the United States. The rather high rate of psychopathology found among the newly arrived immigrants was not well understood. Most of them left their homes voluntary, so how could this have affected their mental state? In the case of people who are forced to flee an unsafe and violent environment and have to withstand the many dangers en route, this is much easier to understand. The article on mental health concludes with two stories told by people who suffered from trauma and were able to find their way to a mental health institution in the Netherlands. Sherally explores ways in which the doctors currently being trained in international health and tropical medicine – the ‘new’ IHTM (AIGT in Dutch) doctors – can become proactively involved in migrant health. Her cry from the heart “not using this potential would be a pity” is valid. In the end, these doctors are trained to work on ‘international health issues’, whether in the Netherlands or elsewhere. WE WELCOME YOU TO JOIN US AT THE SYMPOSIUM ABOUT MIGRANT HEALTH ON OCTOBER 28TH, 2016.

Esther Jurgens

Jan Auke Dijkstra