Main content

Short review on migration and mental health

The first studies on migration and mental health focused primarily on immigration in the Unites States in the beginning of the 20th century. Higher levels of mental health problems or “insanity” were observed among migrants as compared to host populations [1]. Selective migration of mentally ill people was understood to explain this difference. Although hypomanic traits such as impulsiveness, extraversion and risk seeking behaviour may seem to predispose individuals to emigrate, the so-called selective migration hypothesis has never been empirically supported [2, 3]. Furthermore, selective migration is a far less plausible explanation for the higher prevalence rates of psychopathology among individuals with a history of forced migration, such as internally displaced individuals and international refugees as well as stateless and undocumented immigrants [4].

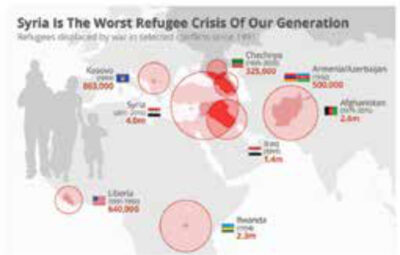

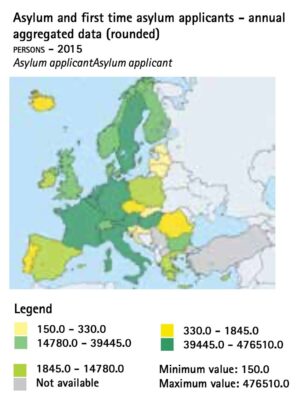

Currently, with conflicts and insecurity in different parts of the world, most attention is given to refugees who are forced to leave their homes as a result of war and violence. It is estimated that in 2015 around 244 million people fled their homes in search of security [5]. In 2015, the United Nations Higher Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) reported that the number of people fleeing Syria because of the war was more than 4 million, far more than the 2.3 million fleeing the Rwandan genocide in 1994 or the chronic conflict in Afghanistan since 1979 [6]. This makes Syria the worst refugee crisis of our generation (Figure 1). In the European Union, almost 1.5 million refugees applied for asylum in 2015 (Figure 2). Refugees typically face multiple challenges during different stages of their migration process, with each stage having a specific impact on their mental health [7].

Pre-migration mental health

Push and Pull factors have been described to explain migration from rural to urban areas as well as international migration. Adverse local conditions will push populations in case of war and violence. In such cases, specific attention should be given to traumas that refugees experience before departure, such as loss of family and friends, physical and sexual violence, and detention and torture. There is, moreover, a loss of social, personal and material resources. Political, societal, educational and/or religious institutions will fail to function, and people will therefore be less able to retain and regain resources. This loss of resources causes loss of social capital of individuals and can traumatize communities. One such resource is the local health care system, the failure of which is reflected in refugees’ pre-departure health status [8].

Transit mental health

The mental health of refugees is often affected during transit from the country of origin to the country of destination. Multiple modes of transport may be used and are often not safe. Accidents on roads or at sea may result in traumatic experiences as well as forced loss or separation from family. Uncertainty about the route and borders, cultural and language differences, and hostile reception in the transit countries may cause stress and anxiety symptoms.

Victims of human trafficking are often exposed to criminal acts in transit, varying from illegal border crossing and forced commitment of illegal acts to physical and sexual violence [4]. Older persons and children form specifically vulnerable groups in transit.

Post-migration mental health

Upon arrival, an initial period of restored hope and peace may be found. However, the post-migration mental health of refugees will eventually depend on a host of different factors. Family problems, poor socioeconomic conditions, lack of opportunities for employment, language problems, uncertain asylum procedures, and discrimination are described as the major stressors experienced by asylum-seekers [9]. Longer asylum procedures were associated with higher levels of mental health problems as well as family and work problems. Prevalence of mental disorders in asylum seekers in the Netherlands was found to be 42% upon arrival. This number increases to 66% at 2 years following arrival, with depression and anxiety being more prevalent. About one-third of the asylum seeker population was found to have posttraumatic stress disorder [9].

For many refugees, resettlement in a new country may ignite a process of “cultural bereavement” [10], a state of grief due to a permanent loss of previously familiar social structures and cultural institutions. The process of adapting to a new culture may also lead to acculturation stress if previously successful coping strategies are no longer available or effective. Moreover, loss of social and economic status and the experience of discrimination and exclusion may have a significant negative impact on the mental health of refugees. The presence of a supportive social network in the host country and a hybrid form of identity, norms and values, consisting of elements of both the “original” as well as the “new” culture [11], are thought to be most beneficial for mental health.

Repatriation mental health

Many refugees that fled their country of origin because of war and violence will continue to feel a state of “permanent transit” and alienation, missing their loved ones and culture left behind. Repatriation is always in their mind, even during ongoing conflict in the country of origin. Few data are available on repatriated refugees. In a retrospective German study of refugees that participated in a state-sponsored repatriation programme, increased levels of psychopathology were found after return. Living and working conditions were mostly unstable [12].

Conclusion

The mental health of refugees is affected by a host of social and cultural factors that may be at play before, during, and following migration [7], as can be seen in Figure 2. Adequate assessment and management of psychiatric problems among refugees should, ideally, incorporate the many ways in which refugees’ social and cultural contexts during each stage of migration may have affected their current experience. This requires a fundamental departure from the purely symptom-oriented approach to mental health assessment and treatment, in favour of an ecological perspective. On the political and social levels, consistent efforts are required to fight discrimination and exclusion, to ensure early participation of refugees in the host communities, and to create employment opportunities during and after the asylum procedure.

Mr. C.

was born in the capital of Syria in 1986 as part of a well-off family with 7 children. After finishing secondary school, he worked as a barber for several years in Syria as well as in Abu Dhabi. In 2012 and 2013, he was arrested for political reasons and held in detention for 3 and 7 months respectively. He was tortured numerous times with a variety of methods. In 2014, he fled to Lebanon were he later heard his father had been killed. He visited psychiatric services on a regular basis in Lebanon for sleeping problems and depressive moods, having been medicated. He decided to look for safety in Europe and fled to the Netherlands via Turkey and Greece. The boat he travelled in capsized in the Mediterranean Sea, but he managed to survive the trip. Once he got to the Netherlands, in September 2015, Mr. C. applied for asylum. He then stayed in different asylum centres in the country until June 2016, when he got an apartment. During the period of applying for asylum, he sought help for psychological complaints several times. He was seen by a general practitioner (GP) and got medication but was not referred to mental health services. Once Mr. C. was able to move to his apartment, he sought help with a new GP and was immediately referred to a specialised mental health institution.

Upon intake, Mr. C. presented with severe psychological suffering. We diagnosed a posttraumatic stress disorder, a depressive episode, and a nicotine addiction. Anxiety and stress had caused severe underweight symptoms (BMI 16.4). He had been previously medicated with a cocktail of tranquilizer, opiates, antidepressants and antipsychotics. His low BMI combined with his medication also caused him equilibrium problems. Severe dental problems and torture-induced scars were found on physical examination. Financial debts were an additional stress factor. After intake, Mr. C. was hospitalized for specialized psychiatric treatment.

Ms. B.

was born in a small village in Sierra Leone in 1989, having lost her mother at the age of 6. During her adolescence, she became aware of her homosexual orientation which put her in danger in the local community. At the age of 20, Ms. B. had to leave school to stay with an uncle following her father’s death. While living with her uncle, she was psychologically and physically abused. She was “sold” to a 75 year-old man as a 3rd bride and became a victim of sexual violence. The threat of a second female circumcision (she underwent the first at the age of 11) made her flee to the capital. Trying to survive without family or other resources, she became the victim of human trafficking until she reached the Netherlands and was forced to work as a sex worker in 2012. Her asylum claim was denied because her story was not considered consistent. Therefore, during her outpatient treatment in a specialized mental health service for traumatized victims of human trafficking, she was undocumented and trying to survive with the help of a local religious organization. After 4 years of juridical procedures, she was recently granted asylum and is currently under psychotherapeutic treatment, trying to deal with the multiple traumatic events she has gone through.

References

- Odegard O. Emigration and insanity. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 1932;4:1-206.

- Giovanni CM, Francesca Mm Fau – Viviane K, Viviane K Fau – Brasesco MV, Brasesco Mv Fau – Bhat KM, Bhat Km Fau – Matthias AC, Matthias Ac Fau – Akiskal HS, et al. Could hypomanic traits explain selective migration? Verifying the hypothesis by the surveys on sardinian migrants. (1745-0179 (Electronic)).

- Swinnen SG, Selten JP. Mood disorders and migration: meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;190:6-10.

- Zimmerman C, Kiss L, Hossain M. Migration and health: a framework for 21st century policy-making. PLoS Med. 2011;8(5):21001034.

- Hall BJ, Olff M. Global mental health: trauma and adversity among populations in transition. European journal of psychotraumatology. 2016;7:10.3402/ejpt.v7.31140.

- Statista. Syria is The Worst Refugee Crisis of Our Generation 2015 [cited 2016 2 Sep]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/chart/3632/syria-is-the-worst-refugee-crisis-of-our-generation/.

- Bhugra D, Jones P. Migration and mental illness. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2001;7(3):216-22.

- Hobfoll S. Resource caravans and resource caravan passageways: a new paradigm for trauma responding. Intervention. 2014;12:21-32 10.1097/WTF.0000000000000067.

- Laban CJ, Gernaat HB, Komproe IH, van der Tweel I, De Jong JT. Postmigration living problems and common psychiatric disorders in Iraqi asylum seekers in the Netherlands. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2005;193(12):825-32.

- Eisenbruch M. From post-traumatic stress disorder to cultural bereavement: diagnosis of Southeast Asian refugees. Soc Sci Med. 1991;33(6):673-80.

- Berry JW. Acculturation: Living successfully in two cultures. International journal of intercultural relations. 2005;29(6):697-712.

- von Lersner U, Elbert T, Neuner F. Mental health of refugees following state-sponsored repatriation from Germany. BMC Psychiatry. 2008;8:88