Main content

In Western Europe and the Middle East, we have been confronted with a refugee crisis of huge proportions during the past two years. The number of refugees is steadily increasing, and many of them are reaching Europe. Providing humanitarian assistance to refugees has up to now been carried out by NGOs and other agencies, but the current situation demands the engagement of a wider section of the medical profession to assist and to advocate for people who have been forcibly displaced.

Global trends

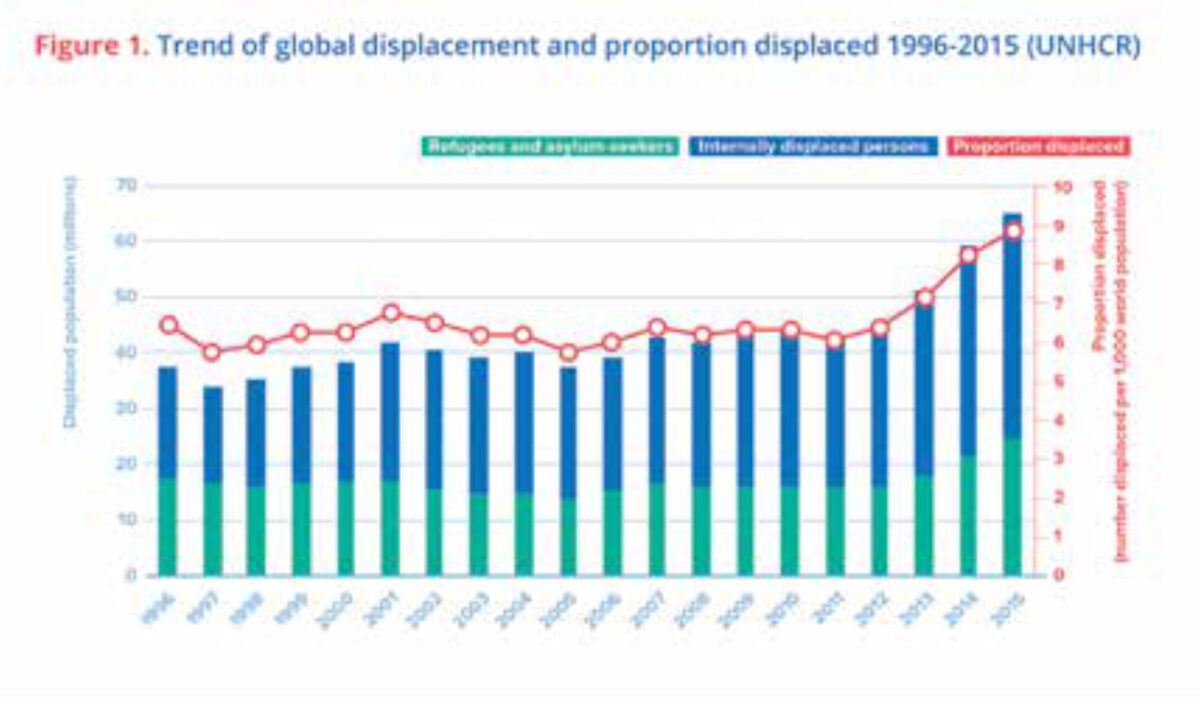

A recent report by the Office of the High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) shows that, in 2015, 65.3 million people were forcibly displaced. This marks a historic high and about a 20 million increase in less than four years [1].

Of that number, just over a third are refugees and asylum seekers while nearly 41 million people are displaced within their own country (Internally Displaced or IDPs). This is significant because, while refugees are more visible, extensive research conducted by the Centre for Research on the Epidemiology of Disasters (CRED) in 2013 showed that adult crude mortality rate (CMR) for IDPs is double that of refugees and also 75% higher in children. It also showed that acute malnutrition is 60% higher in IDPs compared to refugees [2].

Three countries in 2015 (Syria, Afghanistan, and Somalia) were the source of over half the forcibly displaced population. On the other hand, the list of major host countries of refugees included Turkey, Pakistan, Lebanon, Iran, Ethiopia, Jordan, Kenya, Uganda, The Democratic Republic of Congo, and Chad. Despite the media frenzy, European countries didn’t make it to this list in 2015, while a small country like Lebanon, for example, hosted 183 refugees for each 1000 inhabitants (compared to the highest European proportion of 17/1000 inhabitants in Sweden and Malta).

Changing situation and changing needs

In 1997, after having worked through conflicts and crises, MSF compiled its knowledge and experience on working with refugees in a book that has become a major reference to humanitarians in responding to the needs of refugees [3]. What survives, nearly twenty years later, is its insightful list of priorities (Box 1).

| Box 1 MSF Refugee Health Priorities 1997

|

However, the past twenty years have seen many changes besides the sharp increase in forced displacement. The nineties saw most refugees settling in camps such as the massive camps in Congo that followed the Rwandan genocide and were a turning point in providing medical humanitarian assistance to refugees for MSF and others. Some such camps still stand today such as Dadaab, the Somali refugee camp in Kenya, which still hosts tens of thousands of displaced people including a generation that was born there. Camps, however, are no longer the rule. Many refugees today do not settle in contained and reasonably serviceable camps. Also, due to the extreme violence and rapid changes in the conflict, IDPs such as those in Syria and Afghanistan have to move frequently and have no chance to settle at all.

Today, while many of the forcibly displaced are still in camps, many others are not. They are dispersed within host communities who suffer themselves in many cases from poverty and lack of access to essential services. Many are also on the move through precarious conditions that add to the suffering and despair that pushed them into displacement in the first place. A recent study by MSF Epicentre found that, of 425 refugees studied in Calais/France, the average period needed to reach their interim destination was 100 days. 61% of the refugees reported having health problems and over 65% encountered violent events during their trips [4].

What is being done?

As a medical humanitarian organisation, MSF addresses the medical and public health of people affected by crises. This has taken us to treat patients in a wide variety of situations. These include conflicts where we operate and support hospitals and provide basic services in places like Syria, Yemen, Central African Republic and South Sudan, as well as chronic crises such as in the Democratic Republic of Congo. We also help in managing epidemics and outbreaks, for example by operating Ebola treatment centres in West Africa and by carrying out mass vaccination campaigns for cholera in South Sudan and Zambia and for measles in Democratic Republic of Congo. MSF operated in 64 countries in 2015 and saw more than 8.6 million patients. We managed 340,000 HIV patients, vaccinated more than 1.5 million for measles, and assisted in the birth of nearly a quarter of a million babies [5].

The provision of medical care for forcibly displaced populations is an activity we have been involved in for decades, but much of what we face today is different and can be challenging in ways that force us to adapt and change our activities [6]. First, the scale of displacement is one that goes beyond the capacity and willingness of the traditional humanitarian system (in itself not homogenous or in agreement on its goals and methods) to provide help. Moreover, as the conflicts in Syria, Yemen, Central African Republic, and other places have shown us, we have little ability to gain safe and guaranteed access to the people we strive to serve.

Second, the state of displaced persons is different in terms of where they settle. Today, as we face the wave of displacement, we are far from dealing almost exclusively with refugee encampments that provide an opportunity to quantify and logistically reach persons with the services needed. Open settings, host communities, and people on the move add different dimensions to the required response, which need to be understood and addressed [7].

Third, there is the changing legal and political framework. This ranges from the evolving politics and exercise of regulation and power by “traditional host” developing countries to the rapidly changing reaction and regulations of European states over the past two years.

MSF and other actors have reacted in a multitude of ways ranging from providing humanitarian assistance inside Europe, previously unimagined as a necessity, to providing search and rescue in the Mediterranean Sea. Many of MSF’s experiences and reflections have been collected and analysed recently, for example in the Refugee Survey Quarterly [8]. In the meanwhile, humanitarian assistance continues its “traditional” work, ranging from medical care to providing water and sanitation and shelter in refugee camps, including those that have stood for over twenty years such as Dadaab and more acute centres such as the refugee camps of the Burundians in Tanzania.

The change in the situation is forcing a change in reflection in MSF as well as in other humanitarian actors, which impacts our technical, political, and ethical perspective. On the technical side, we are compiling our knowledge and experience to update our list of priorities. The twenty-year-old list that has served us and others well requires an update that addresses the changing circumstances and does not only take camps into account in order to enable us to serve the medical humanitarian needs of today’s forcibly displaced people. On the political side, we will speak out about the situation and about the needs of displaced people and advocate for sustained and active humanitarian assistance in the shadow of a lack of political will and dwindling resources.

And finally, on the ethical side, as humanitarian actors we must continue to examine our ethical obligation and position vis-à-vis the displaced people we are serving and the powers that control their fate. How does this drive us to act, where do we stand, and how should we advocate?

What should be done?

Besides the work of medical humanitarian actors globally, medical professionals in host countries, including Europe, have an obligation towards people who arrive in their countries. There are the sick who need treatment, children who haven’t got their vaccination, and traumatised persons who need psychological and social support. We have a medical as well as a humanitarian obligation, imposed on us by medical ethics, to providing impartial care to those who need it most. This is taking place in many cases. We have seen it on the Austrian-Hungarian border as well as in Greece, where refugees were crossing en masse. Many volunteers, including medics, provided food, care, medicine, and guidance to people who were exhausted and in despair. Yet, physician and nurses are not merely about diagnosis and treatment protocols. In my native Levantine Arabic, a physician used to be called “Hakeem” in the old days, a word that translates as “wise man”. This is because, decades ago, physicians were perceived to have the education and knowledge that allowed them to treat people but also defend the defenceless and arbitrate disagreements.

Conclusion

Hannah Arendt wrote her article We Refugees in 1943; much of it still applies today [9]. She told us ‘a refugee used to be a person driven to seek refuge because of some act committed or some political opinion held. Well, it is true we have had to seek refuge; but we committed no acts and most of us never dreamt of having any radical opinions’.

Today, we have people who need safe passage, access to health care, and all the help they can get to survive. They are, after all, fleeing conflicts fuelled by many of the very states refusing to provide them with shelter. MSF and other humanitarian actors are doing a part of what needs to be done, but this is no longer only the duty of medical humanitarian actors. The medical profession as a whole should be actively involved in treating refugees, supporting them, and speaking out on their behalf.

References

- UNHCR, 2016, Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2015 (https://s3.amazonaws.com/unhcrsharedmedia/2016/2016-06-20-global-trends/2016-06-14-Global-Trends-2015.pdf)

- CRED, 2013, People Affected by Conflict 2013: Humanitarian Needs in Numbers (file:///D:/Users/tal/Downloads/PAC2013%20(11).pdf)

- MSF, 1997, Refugee Health: An Approach to Emergency Situations (http://refbooks.msf.org/msf_docs/en/refugee_health/rh.pdf)

- MSF Epicentre, 2016, Evaluation de l’état sanitaire des réfugiés durant leurs parcours et à Calais, Région Nord Pas de Calais Picardie, France (http://epicentre.msf.org/sites/preprod.epicentre.actency.fr/files/1073_%20Rapport%20Calais_%20version%20finale_0.pdf)

- 2016, MSF, Internal Activity Report 2015 (http://www.msf.org/sites/msf.org/files/international_activity_report_2015_en.pdf)

- 2013, Abu-Sada and Serafini, Forced Migration Review, Humanitarian and Medical Challenges of Assisting New Refugees in Lebanon and Iraq (http://www.fmreview.org/sites/fmr/files/FMRdownloads/en/detention/abusada-serafini.pdf)

- UNHCR, Policy on Alternative to Camps (http://www.unhcr.org/5422b8f09.html)

- Oxford, 2016, Refugee Survey Quarterly: Humanitarianism and the Migration Crisis. Volume 35, Number 2. (http://www.msf.org/en/article/20160811-humanitarianism-and-migration-crisis)

- 1943, Hannah Arendt, We Refugees (http://www-leland.stanford.edu/dept/DLCL/pdf/hannah_arendt_we_refugees.pdf)