Main content

Esther Jurgens serves as editor-in-chief (in the period between 2020 and 2023: ad interim, together with Ed Zijlstra).

This edition of MTb centres around saying goodbye and reflecting. At the same time, we have a forward-looking perspective. That is also the spirit I want to bring to my contribution to the Speaker’s Corner – a space reserved for the voices of recent editors-in-chief in this final edition of MTb. In my piece, I want to reflect on the sources of my inspiration and what continues to drive me: a deep belief in taking an interdisciplinary approach to tackle the complex issues and dilemmas we face in global health.

My academic background in medical sociology laid the foundations for the way I approach global health. From the very beginning of my studies and career, I realised how social scientists and medical professionals can – or rather need to – complement each other when it comes to addressing the concrete realities of global health. The solution is not the proverbial magical bullet – a vaccine, a new drug or a breakthrough treatment – as sometimes (ineffective) global responses to combatting the HIV/AIDS epidemic and the COVID-19 pandemic have shown. Medical innovations alone are not sufficient, as successful implementation equally depends on addressing the wider context and broader social and structural determinants, including discrimination, financial limitations or treatment adherence, and active engagement of communities in shaping sustainable health solutions.

In this column I want to tell the story of how these insights matured and developed throughout my professional work – working for UNICEF in Latin America and the Caribbean, consultancy work in global health, with Maastricht University and the NVTG. I chose three examples from my work over the past three decades of working in development assistance, with a particular focus on sexual and reproductive health and rights (SRHR). The three examples reflect my inspiration and approach – grounded in the firm belief in cross-fertilisation between disciplines, allowing quantitative and qualitative research to complement each other.

First example: ‘Men at risk’

In the early 1990s, a year after world leaders endorsed the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC: a political charter, comparable with today’s Sustainable Development Goals) – with the notable exception of the United States – I began working with UNICEF in Belize, Central America. At the time, our guiding principle was “Health for All by the Year 2000”, a slogan that captured a somewhat hopeful momentum of the era because of increased immunisation from 10% in the early 1980s to nearly 70% by the decade’s end – almost eradicating polio and decreasing infant mortality levels, partly as a result of increased access to safe water and sanitation.

Due to the small size of the UNICEF office – mirroring the country’s population of less than 200,000 – I was fortunate to be involved in a wide range of areas. As a recently graduated medical sociologist, I worked with the Medical Statistics Bureau to strengthen Belize’s vital registration systems, from remote rural villages to the capital, by collecting data for UNICEF’s situation analysis of children and women, and contributing to surveys on infant mortality and diarrhoeal diseases. It was also a time when the focus of international health began to shift toward adolescents – an age group long overlooked in health programmes. Another approach that took root in the early 1990s was the introduction of gender mainstreaming as a tool to promote gender equality across all levels. [1] Although the concept was already introduced at the 1985 Nairobi World Conference on Women, it took more than a decade to be formally adopted as a universal strategy for policy and programming. [2] This was no different for UNICEF. As a children’s fund, its early perspective on women’s needs was primarily shaped by their reproductive role – the “R” in Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights (SRHR).

My work with the Women in Development Department within UNICEF, collaborating with NGOs and the Government Department of Women’s Affairs, taught me many lessons, amongst others the persistent and far-reaching implications of gender imbalances in society. For example, addressing violence against women required a multi-faceted package of interventions. This included support for the passing of the Domestic Violence Bill, the provision of legal assistance and medical care to victims of violence (now referred to as ‘survivors’), and the establishment of safe spaces for girls and women in need of protection. Yet I felt something was missing. If we are truly committed to breaking the cycle of violence, we must examine the underlying conditions that give rise to or sustain structural power imbalances and abuse. This means acknowledging and addressing the toll that gender inequality takes not only on women and girls, but also on boys and men—particularly through rigid stereotypes that uphold harmful forms of masculinity. Understanding gender equality merely as women’s empowerment, or mentioning ‘women and men’ without considering their different lived realities is simply not enough. In addition, women and men are not homogenous groups. Addressing their needs meaningfully requires looking beyond and considering characteristics such as age, ethnicity, sexual orientation, and social status. From then on, my understanding of gender equality as an inclusive and multidimensional concept has only deepened. Yet we can’t afford to become complacent. This holistic gender approach – carefully built up since the mid-1980s – is at risk. In the current political climate, marked by the Trump administration’s ban on terms of gender, gender identity and any reference to gender ideology – is systematically being dismantled.

… back to the early 1990s, where I had the opportunity to meet Errol Miller, the Jamaican author of Men at risk, during his book tour in Belize. In this book, he explores changing gender dynamics in American and Caribbean societies, and addresses the often-contradictory nature of patriarchy and the ways in which masculinity and femininity are socially constructed and shaped over time within the Caribbean context. Insights like these, combined with my research and programming experience in the country, reaffirmed earlier notions on what it takes to develop effective programmes and policies – whether in health, education or beyond. What is required is a phase zero, in which we take time to genuinely try to look at the root, underlying, causes of health problems, and the context in which they occur. Failing to understand them makes our efforts superficial and, at worst, counterproductive.

In an effort to challenge traditional gender roles and expand employment opportunities for young girls in Belize, I proposed supporting a vocational training programme that would enable adolescent girls to enter non-traditional professions – such as mechanics and air-conditioning repair. It nearly failed, as UNICEF policies required funds to be channelled through government ministries, and stand-alone or so-called “isolated projects” were discouraged. Of course, I understood the rationale for this, though I doubted whether the Ministry of Education at the time would have prioritised such a progressive gender-equity initiative. Luckily, the programme got implemented.

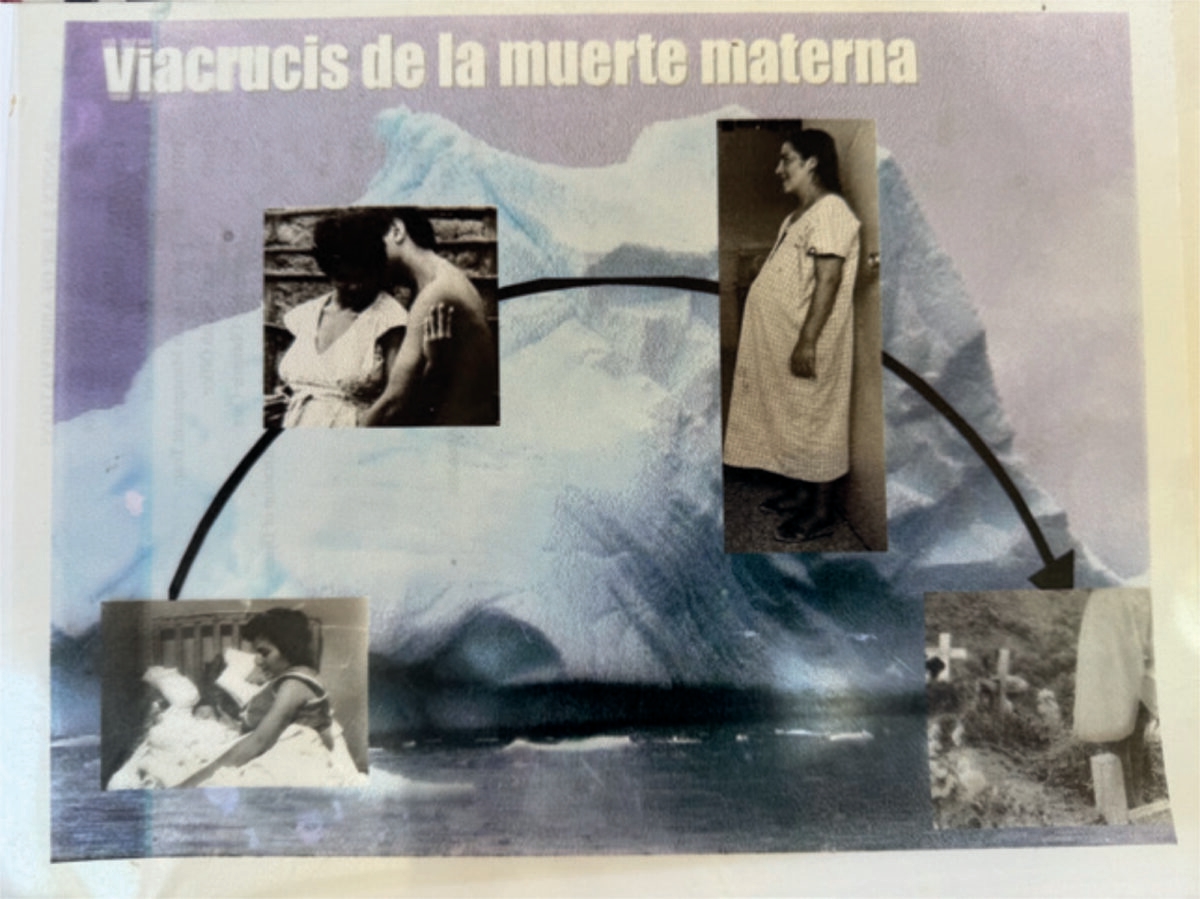

Second example: Viacrucis de la muerte materna

Despite my earlier idea to leave the UN behind, I found myself returning to UNICEF in 1999 – this time with the Regional Office for Latin America and Caribbean (TACRO). Once again, I worked within Social Monitoring and Evaluation, and what is now called the “Gender Unit”. Assignments that reinforced my belief in cross-sectional and interdisciplinary approaches were the development of two regional position papers: one to adapt the globally formulated goals on the reduction of maternal mortality (MM) to the Latin American and Caribbean (LAC) context, and the other to shape a regional stance on adolescent health.

I’ll focus here on the regional maternal mortality strategy, as it is a perfect example that shows the importance of combining medical and sociocultural perspectives when addressing the persistent reality of preventable maternal death. While regional maternal mortality averages in LAC were lower than in parts of Africa [3], they masked stark disparities between countries and within countries. My co-researcher on this project was a Cuban gynaecologist, and together we conducted fieldwork in several countries in the region. In Lima, Peru, she started with examining the state of the blood bank. While driving in our four-wheel drive to a remote health post in the Andean highlands of the country, I asked myself how on earth a pregnant woman would be able to walk to the centre for the recommended prenatal controls, let alone get there in time in case of an emergency. That the health centre lacked a quality-controlled stock of blood when in need of emergency obstetric care came as no surprise.

Still in the highlands, but in more urban areas, we encountered a different problem: the near-empty waiting rooms of a well-equipped maternal ward. Through discussions with local women, we learned that women were hesitant to use these services – not so much because of presumed medical care, but mostly because of cultural barriers: the white coats of the doctors, the birthing position, and the exclusion of traditional birth attendants (TBAs) [4] – who to them played an important role in emotional support. These were not just medical issues, but rather issues of cultural awareness and receiving culturally appropriate maternal health care.

These insights formed the foundation of a comprehensive regional strategy that recognised the full spectrum of factors influencing maternal health. Too often, the discourse around maternal mortality has focused exclusively on failures within the health care system—such as inadequate emergency obstetric care. As we wrote in the strategy: “There is no doubt that a great number of maternal deaths could have been prevented if these women had reached a health service in time and received obstetric care of respectable quality. But an analysis focused solely on the immediate, clinical causes of maternal mortality ignores the broader web of responsibility—one that includes not only the state, but also families, communities, and everyone involved in supporting a woman through pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period.” [5]

In the strategy, we proposed an integrated approach and outlined the barriers to accessing at least the basic minimal standards of health care services: economic, geographical, and cultural barriers. [6] Through this lens, we presented case study analyses – including the illustrative “viacrucis” (cross-bearing) of Mrs. X – demonstrating how her death could have been prevented. It showed the need for action at all levels: emergency clinical responses, targeted interventions for high-risk groups, and, importantly, integrated and rights-based policies to address the fundamental causes of poor maternal health outcomes. Avoidable maternal deaths are not just failures of care; they are violations of human rights.

Third example: Mutual learning, collaboration, and curriculum development

The final set of examples reflects three curriculum development initiatives – one in maternal health in Georgia, and the other two in climate change and health in Bangladesh. These projects reaffirmed the importance of mutual learning and interdisciplinary collaboration.

Central to our work in Georgia – a former Soviet republic, eager to reform its health care system, as it was still predominantly hospital-based and curative in orientation – was the repositioning of midwives within the maternal health system. The goal was to enhance their competences (by designing a midwifery curriculum at the University in Tbilisi) and to work on more systemic changes by granting them a more central role in prenatal and delivery care. [7] “You can write a curriculum in an evening”, remarked our partner at Tbilisi State Medical University at the beginning of our three-year collaboration on designing a midwifery training programme. While drafting a curriculum may indeed be relatively quick, the transformation of the institutional, cultural, and professional context in which midwives operate – and enabling them to take on this central role – is a far more complex process, which takes much, much longer. In this programme, we also collaborated with a gynaecologist who had bought a previously state-owned hospital – taking advantage of the country’s shift to market liberalisation and the introduction of private health care. This allowed him to introduce a new model of maternal care – elevating the role of midwives – and to implement a cross-subsidisation scheme that guaranteed access to quality care for pregnant women regardless of their financial means. The restructuring of professional roles, education and interprofessional collaboration – particularly across traditionally rigid boundaries between gynaecologists, midwives and nurses – were crucial elements to the success of the initiative.

Maastricht University, a pioneer in Problem Based Learning (PBL), was invited to serve as a technical partner in two Erasmus + programmes. [8] The first, the TRANS4M-PH programme [9] supported three universities in Dhaka, Bangladesh in redesigning nine (public) health courses. The second, the ongoing ACCESS4ALL programme, focuses on climate change & health education. It encourages students and young professionals to understand both the immediate and the root causes of climate change and to analyse how structural factors worsen its impact. In these curricula, the PBL approach enables students to develop a critical lens in order to dive deeper and to question dominant narratives and the myths, misconceptions and simplifications in many public debates on climate change. Students are invited to embrace complexity – to unravel the multi-causal nature of current day challenges in global health, like understanding the impact of climate change on health. This is the precursor to developing more nuanced and interdisciplinary approaches to address contemporary global health problems.

As with the midwifery initiative, implementing such change requires more than enthusiasm from a core group of colleagues. While the participating faculty quickly saw the benefits of the new approach, embedding these innovations into the wider academic ecosystem proves more challenging. Many institutions are still rooted in traditional modes of instruction and knowledge transmission. Transforming these mindsets will take time.

Epilogue

Finally, I return to my longstanding involvement with Medicus Tropicus, later MT, MTb, and now Global Health Perspectives. From the early days of my work with the NVTG, I contributed to the journal – first as an editor, later as editor-in-chief. In the early days, editorial work was relatively straightforward. The journal, then in Dutch, was a combination of news from the Society and articles. Over the years, and because of my work as policy advisor, I became a more and more stable factor in the editorial team, as I had been part of the journal’s transformations over the past decades.

An essential theme throughout this journey has been, and still is, my commitment to bridging the gap between clinical medicine and public health, between the biomedical and the social sciences. The 2007 edition of the ECTMIH – hosted in the Netherlands by NVTG and partners – was illustrative, as we explicitly articulated the importance of cross-fertilisation between disciplines and professions. It’s a spirit that continues to guide my work and thinking up to today.

Lastly, but certainly not least, I would like to thank all the colleagues with whom I’ve had the privilege of working. Not only was it fun and enjoyable to work with you, I also learned a lot.

References

- Gender mainstreaming, basically an approach that takes into account both women’s and men’s interests and concerns. “Mainstreaming a gender perspective is the process of assessing the implications for women and men of any planned action, including legislation, policies or programmes, in all areas and at all levels. It is a strategy for making women’s as well as men’s concerns and experiences an integral dimension of the design, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of policies and programmes in all political, economic and societal spheres so that women and men benefit equally and inequality is not perpetuated. The ultimate goal is to achieve gender equality.” United Nations. “Report of the Economic and Social Council for 1997”. A/52/3.18 September 1997.

- Known as the Beijing Platform for Action, an agenda for women’s empowerment, declared at the Fourth United Nations World Conference on Women in Beijing (1995). https://www.un.org/womenwatch/daw/beijing/platform/plat1.htm

- At that time the average rates in LAC were 189/100,000 live births, and the risk of death during pregnancy and live birth was 1 in 130 – with the highest rates in Bolivia, the Dominican Republic, Haiti, Honduras and Peru.

- See the shifts in considering the role of TBAs during pregnancy and childbirth, which at that time was subject to highly debated policy discussions.

- TACRO: health / women and gender equity areas / Maternal mortality – strategy for its reduction in Latin America and the Caribbean. Regional Position Paper. 1999. The subtitle we chose for the paper was ‘Viacrucis de la muerte materna’.

- The proposed framework for assessing and analysing maternal health included the need to address underlying factors (status of girls and women in society and women’s vulnerability to poverty, among others); the intermediate causes (health and nutritional status of women, reproductive and maternal health rights, and knowledge, attitudes and behaviour that influence female health); and immediate causes (medical complications during pregnancy, childbirth, or postpartum).

- Enhancing quality of care: Upgrading the knowledge and skills of midwives in Georgia (2008-2011). Implementing partners in Georgia: HERA XXI; Tbilisi State Medical University; Georgian Obstetricians and Gynaecologists Association. Implementing partners in the Netherlands: ETC Foundation; Rotterdam Academy of Midwifery; International Confederation of Midwives.

- The Adapting Climate Change Education Skills and Sustainability for Advancing Locally-led Solutions (Access4All) Programme. Partners: James P Grant School of Public Health, BRAC University, Bangladesh; Independent University of Bangladesh; University of Liberal Arts, Bangladesh; Maastricht University, The Netherlands; Heidelberg Institute of Global Health, Heidelberg University, Germany. See: https://www.access4allhub.com.

- The Transformative Competency-Based Public Health Education for Professional Employability in Bangladesh’s Health Sector (TRANS4M-PH) Programme, running from 2019 – 2021. See: https://trans4mph.org