Main content

Even those without sight can see a haunting phantom drifting through our world called autocracy. Our work field is under siege; the World Food Programme and USAID have been erased by dictatorial authority. In the past, justice used to be a strong check on the abuses of power, but today, in the daily dazzle of distorted logic, we see autocracy dismantling justice at high speed. It’s not just the future of our own work field, as international law and the most basic moral principles are at stake. Despite the Dutch government slashing 50% of the Development Cooperation budget, our work remains crucial: poverty, maternal mortality, tuberculosis, and HIV will not disappear by ignoring them. After critically assessing this onslaught, I anticipate that non-governmental organisations will soon develop significant new forms and modus operandi. Moreover, resilience is our trademark.

In these gloomy days, I want to boost your morale and tickle your curiosity by arguing that it’s never too late to do a PhD. Perhaps this is the right moment to deepen or redirect your career and start an academic adventure tour. Before delving deeper into my own research journey’s why, how, and substance, I will first take you through some pivotal experiences in my 35-year international health career that prepared the ground for my recent PhD.

Infected

In 1990, I began my international health career at the Queen Elizabeth Central Hospital in Blantyre, Malawi. To become a competent ‘tropical doctor’, I completed an extensive 18-month rotation under the guidance of dedicated Dutch and international specialists. During this time, Prof. Anthony Harries introduced me to the clinical aspects of tuberculosis and HIV. He infected me with a lifelong scientific mindset through a joint study on the cost of antibiotic treatment. [1]

Later, as a district health officer in several Malawian district hospitals, I found myself overwhelmed by hospital management issues and especially by the tsunami of patients with HIV infection. We also had no treatment available yet in those days. This demanding environment left little room for research activities, but an inquisitive mindset helped win a big EU grant for the new Thyolo District Hospital.

Curiosity

In 2000, after nearly a decade in Malawi, I accepted the technical lead to revise and integrate the Indonesian national leprosy and tuberculosis specialist curricula in Makassar, Sulawesi. The Makassar National Leprosy and Tuberculosis Training Centre (PLKN) played a vital role in training young doctors, postgraduate specialists, and nurses. The diversity of training backgrounds highlighted the need to identify each professional’s specific training requirements. In response, our curriculum team established several problem-based learning modules based on a strong set of core competencies. However, this top-down approach resulted in a relatively rigid, one-size-fits-all training structure.

During this traditional curriculum development process, I became curious whether building a training from the ground up using self-assessment and asking professionals about their actual learning needs would result in a more flexible training and learning process, better tailored to the specific context and needs of the various medical cadres.

Training 15,000 midwives and being thrown under the bus

To enhance family planning and lower maternal mortality, I worked from 2003 to 2006 for Johns Hopkins University as a senior quality & performance improvement advisor for the Indonesian USAID-funded reproductive & maternal health programme. Our training team proved that a self-assessment questionnaire could be particularly valuable in helping individual midwives, who often provide service without a supervisor or colleague to guide their performance, to define areas where they felt the need to improve their service quality. Self-assessment also assisted the training team in determining, organising, and prioritising medical competences and customising training and learning to enhance the quality and performance of midwives’ services.

In partnership with the Indonesian Midwifery Association and the Ministry of Health, this programme trained 15,000 private midwives and created a sustainable quality assurance system for “Quality Private Midwives” using a peer review approach based on self-assessment scales After this fruitful programme, it was evident that self-evaluation contributed to the qualified midwives’ improved performance and quality in the “Bidan Delima”. [2]

Nevertheless, we also found that some midwives produced inaccurate self-assessments, which raised the critical question of how accurate our self-assessment tools were. In 2005, US Republican politics kept liberal contractors like Johns Hopkins University out of the highly polarised reproductive health field (sounds familiar?). So, I never researched the validity and reliability of our self-assessment instruments for midwife competencies. In the end, I was thrown under the bus and needed to get a new job.

Unexpected opportunities

From 2006 to 2011, Padjadjaran University in Bandung, Indonesia (UNPAD), Antwerp University (Belgium), Maastricht University, Radboud University, the Nijmegen Institute for Scientific Practitioners in Addiction (NISPA), and CORDAID formed an international consortium called IMPACT (Integrated Management for Prevention and Control and Treatment of HIV/AIDS). This consortium received a 5-year European Commission grant (Grand: Santé/2005/105-033) for the prevention, control, and treatment of HIV/AIDS and battling the combined HIV/IDU epidemic among intravenous drug users in West Java province (population: 40 million). Being the general manager (COP) of this academic partnership was an enormous honour and the capstone of my international health career.

Evidence of injected drug use, addiction treatment, and the resulting HIV issues was scarce in Indonesia and unavailable in Bandung, West Java. IMPACT aimed to establish an Addiction & HIV centre of excellence. As a result, we started baseline epidemiological studies and needs assessments to study and develop multidisciplinary approaches for tailoring evidence-based prevention to the development of combined HIV and Addiction prevention, care, and treatment programmes. My task was “getting the job done”: facilitating multi-disciplinary research and implementing evidence-based treatment. This effort resulted in an additional spin-off of over 20 PhDs of young Indonesian (and some Dutch) scientists. At the end of the IMPACT programme, this new scientific knowledge formed the brick-and-mortar for the Indonesian postgraduate short course in addiction medicine (ISCAN), which, together with the construction of the addiction medicine training needs assessment self-assessment scale (AM-TNA), measuring self-perceived training needs in addiction medicine, offered an unexpected opportunity to start my PhD journey.

Why

By the end of the IMPACT programme in 2011, the Indonesian addiction workforce was still too small and poorly trained, leading to a significant substance use disorder (SUD) treatment gap. We developed the Indonesian evidence-and-competence-based short course in addiction medicine (ISCAN) to address this treatment gap. From the health care provider’s perspective, I explored a self-assessment approach (AM-TNA) during the training needs assessment process.

The AM-TNA scale can only be used as a valuable instrument for addiction medicine curriculum development and the assessment of training needs, training gaps or training progress if an evaluation of reliability and validity – critical requirements for any psychometric instrument – is well established. As a result, my research aim was focused and modest: to develop a valid and reliable self-assessment instrument to measure training needs, gaps, and progress in addiction competencies. My dissertation’s primary focus is on the internal validity of the AM-TNA, and it leaves external validity and the effect of the combination of the AM-TNA with objective external assessment wide open for future exploration and discovery.

How

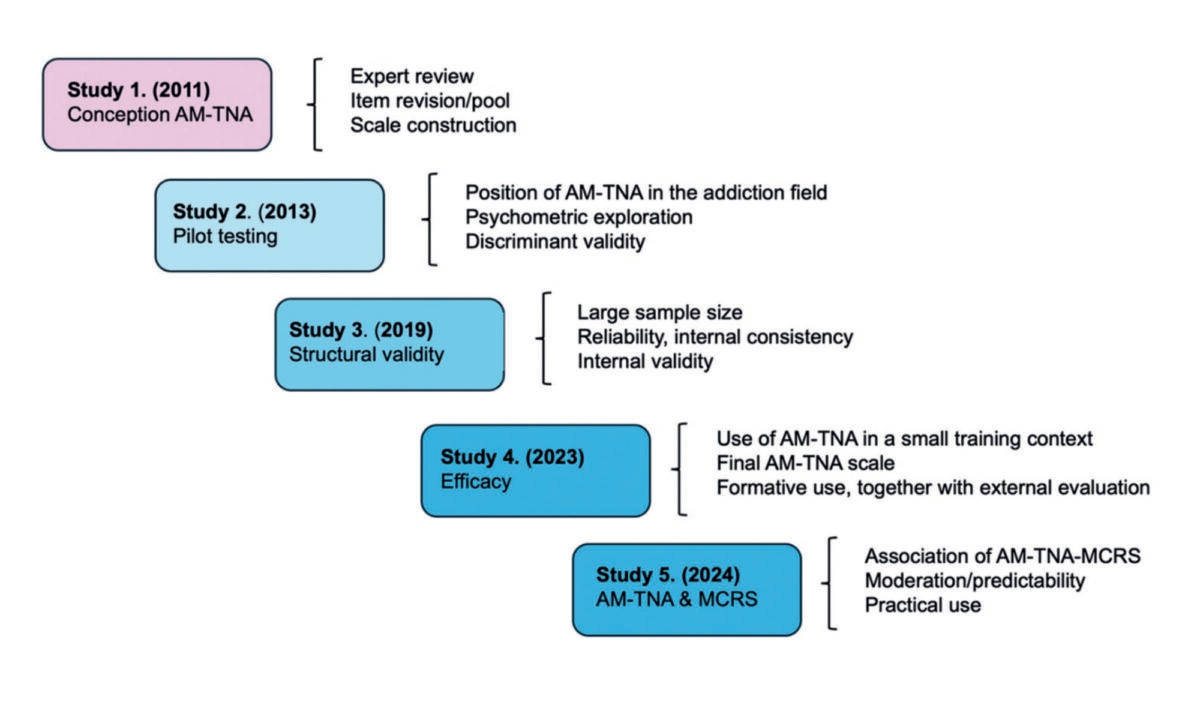

The psychometric and practical value of the AM-TNA was gradually established in five studies, which evolved from each other. The first four studies have been published, and the last one has been approved but not yet published (April 2025). The first study showed that the AM-TNA could guide the ISCAN curriculum design. To our delight, the instrument also proved to have some initial psychometric value, despite the small sample size. This result was only indicative though, given the small sample size (N=27). But it was a strong motivator for the following study. [3]

The second study tried to define the position of the AM-TNA scale in the bigger picture of the changing addiction paradigm shift. In this study, we could confirm the initial psychometric value. These first psychometric details of the AM-TNA scale were promising, but we considered the assessment scale still in its infancy. At that moment, we acknowledged that sample size was one of the biggest challenges in establishing the psychometric value of the AM-TNA scale. [4]

This issue was tackled in the third study by pooling data from four countries (Indonesia, Lithuania, Ireland and the Netherlands), resulting in a larger sample size (N=428) for the final in-depth validity and reliability study of the AM-TNA scale. Having now a well-established AM-TNA scale with excellent internal validity and reliability, curiosity took over again. Subsequently, we studied the efficacy of the scale in a small local training setting. [5]

In study number four, the AM-TNA measured increased addiction competence over four years in groups of psychiatry specialists in training; in our eyes, the instrument had matured. During this study, our focus turned to more practical assessment aspects, and we concluded the study with the advice to use the AM-TNA from the learning experience perspective and triangulate its results. [6]

In the final study, global ambitions took over, and we studied the association of physicians’ stigmatising attitudes to people having SUD (as measured by the MCRS) and perceived training needs (as measured by the AM-TNA). We were able to confirm that the attitude of addiction professionals predicts training needs. Addiction knowledge, attitudes, and skills are intimately related, and our study confirmed that attitudes predict self-perceived SUD knowledge and skills training needs. [7]

Looking back

“Life is what happens when planning other things”, said John Lennon. This proverb also applies to my PhD trajectory. I had abandoned the idea of ever getting a PhD for a long time – as I never found a good match between a challenging subject, a professor and me – until my conversation with Prof. Cornelis de Jong, visiting the IMPACT programme in Bandung Indonesia as a technical advisor for the development of an Indonesian short course in addiction medicine on 24 April 2010. That specific moment kicked off a decade-long journey of curiosity and learning.

First, conducting research on the validity of the self-assessment AM-TNA Scale by a free exploration of a topic in-depth, gaining a deeper understanding, answering questions that have not yet been asked and answered, and making a small but meaningful contribution to this specific though small part of medical education, was a great way to improve medical training practice and at the same time satisfy my curiosity and desire to learn.

Getting articles on medical training published in addiction journals proved challenging, especially during the COVID crisis. One article took over two years to get published: it took one editor 51 weeks to reject our submitted article, and another journal required over a year to start the review process. As a result, I learned to be patient, deal with rejection and frustration, and be persistent. I also learned that publishing my research in a specialised medical education journal was easier than in addiction journals.

As an external researcher (‘buiten promovendus’ in Dutch), I did everything to avoid becoming a lone maverick working in isolation. The technical-scientific and social support from my supervisors, colleagues, and peers in the Netherlands and abroad was essential during my PhD journey. The feedback from other ‘struggling’ PhD candidates during retreats, especially for improving academic writing and reasoning, proved very supportive. I love teaching, but this PhD journey, which ended on April 24 last year with a PhD thesis defence [8], added a lot of purpose and passion to my final career: training psychiatrists and addiction physicians in public health and medical leadership at the Dutch Addiction Medicine Specialists Course (MIAM/NOVA) in Nijmegen.

I loved this protracted research track and strongly advise my international health colleagues to consider a PhD track. For some, the passion will outweigh the struggle; for others, though, the challenges will overshadow the excitement. Discover for yourself if it’s more fun or more of a burden for you. Give it a go, and start with a rough plan. Find a supportive senior professional, and try ONE article! If I can do it, you can do it as well!

Recent developments

Last year, the Training Committee of the International Society of Addiction Medicine accepted the AM-TNA scale as the global benchmark to assess training gaps in over 44 countries: a memorable milestone in a decade-long research trajectory. [9]

References

- Harries, A. D., Willems, H., Pinxten, L., & Kumwenda, J. (1993). Use and costs of antimicrobial drugs in medical wards of a central hospital in Malawi. Journal of Infection, 27(2), 137-142.

- Bidan Delima: https://www.bidan-delima.id/

- Pinxten WJL, De Jong C, Hidayat T, Istiqomah AN, Achmad YM, Raya RP et al. Developing a competence-based addiction medicine curriculum in Indonesia: the training needs assessment. Substance Abuse. 2011;32(2):101-7.

- Pinxten WJL, Jokubonis D, Mazaliaukiene R, Achmad TH, De Jong CAJ. (2013). Comparing the training needs assessments for a competence-based addiction medicine curriculum in Lithuania and Indonesia: Strengthening the new addiction medicine paradigm. International perspectives on training in addiction medicine (97-113). New York, Routledge.

- Pinxten WL, Fitriana E, De Jong C, Klimas J, Tobin H, Barry T et al. Excellent reliability and validity of the Addiction Medicine Training Need Assessment Scale across four countries. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019;99:61-6.

- Pinxten L, Jokubonis D, Adomaitiene V, Leskauskas D, Cornelis AJ, De Jong. Self-Assessment of Addiction Medicine Core Competencies in Four-Year Groups of Psychiatrists in Training: Efficacy of the Addiction Medicine Training Needs Assessment Scale in a Local Training Context. European Addiction Research. Accepted for publication on November 24, 2022. DOI: 10.1159/000528409.

- Pinxten, W. L., Fitriana, E., Jokūbonis, D., Adomaitiene, V., Leskauskas, D., Jong, C. A., & Hutschemaekers, G. J. (2023). Physicians’ attitudes towards patients with substance-related disorders predict training needs in addiction medicine: challenges and opportunities for strengthening the global addiction medicine workforce. Accepted for publication by BMC Medical Education.

- Mind The Gap: Validation of the Addiction Medicine Training Needs Assessment Scale https://lnkd.in/ebUpS7Ez

- DeJong, C. A., Welle-Strand, G., Hanafi, E., Pinxten, L., Bhad, R., & Arunogiri, S. (2025). Global assessment of training needs in addiction medicine. European Addiction Research, 31(1), 75-85.