Main content

Patrick Adonga* is a 45-year-old farmer living in a small village in Northern Uganda. He is married with four teenage children. Recently he has been in a traffic accident with his motorcycle. He sustained only minor bruises, but became anxious after the incident. For as long as he can remember he has recurrent nightmares of drowning and while drowning, the water turns into blood. He believes he is cursed. As a teenager he was abducted by a rebel army and forced to become a child soldier. During his time with the rebel army he was forced to loot, rape and kill people, including some of his friends. At the moment, however, he hardly remembers anything about his time with the rebel army. He never talks about his experiences. In the beginning of his married life he often had ‘attacks’ when he would become very aggressive towards his wife. Afterwards he would not remember anything about the events. Since the motorcycle accident these attacks have come back and his recurring nightmares have become more frequent and intense. He is unable to work on his land during the day, because he is too exhausted from the nights.

When working in a (post) conflict setting, as a doctor, nurse, psychiatrist, researcher or project coordinator, one often encounters people who have experienced several adversities and are dealing with numerous mental health and psychosocial challenges. Especially after war, conflict, violence and natural disasters mental health symptoms (distress, anxiety, worrying, intrusive memories, grief, sadness, sleeping problems and aggression) are widely prevalent. People who have experienced adverse events (e.g. witnessing or experiencing violence or forced migration) can feel easily scared, irritable, or have intrusive memories, flashbacks or nightmares. In some cases these difficulties can result in a posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). People avoid to talk or think about past adverse experiences, it is simply too painful and difficult to talk about. How can you find the words to verbalize such horrible and inhumane experiences?

The current evidence based practice states that PTSD can best be treated with trauma-focused exposure treatment. This means that the best way to overcome adverse experiences is to actively remember and re-experience these events. In Europe and the US academically schooled and highly trained counsellors and therapists offer individual psychotherapy such as Eye Movement Desensitization Reprocessing (EMDR) or Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT) to people with PTSD. However, in (post) conflict areas the expertise and human resources to offer such specialised treatments are often absent. Furthermore, long-term treatments are not feasible because people are often on the move and are unable to commit to regular appointments due to other obligations (e.g. working on the land, logistical issues, taking care of family members). When working in these contexts professionals are often faced with people like Patrick Adonga: people who have experienced several adverse events and are possibly suffering from PTSD, but with no or limited treatment methods available.

To tackle the challenge of offering appropriate treatment to people suffering from PTSD with limited resources available, Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) was developed by the international NGO Victim’s Voice (Schauer, Neuner & Elbert, 2011). NET is an individual, culturally sensitive and short-term psychological treatment aimed at recovery from adverse/ traumatic experiences and associated symptoms of PTSD. This alternative trauma focused therapy was especially created for professionals working in (post) conflict settings. It has been developed, designed and tested in several countries (Uganda, Sri Lanka), where it proved to be an effective method to reduce PTSD symptoms, both for children and adults (Catani et al., 2009, Neuner et al., 2008a, 2008b, 2004, Ruf et al., 2010, Schaal, Elbert & Neuner, 2009).

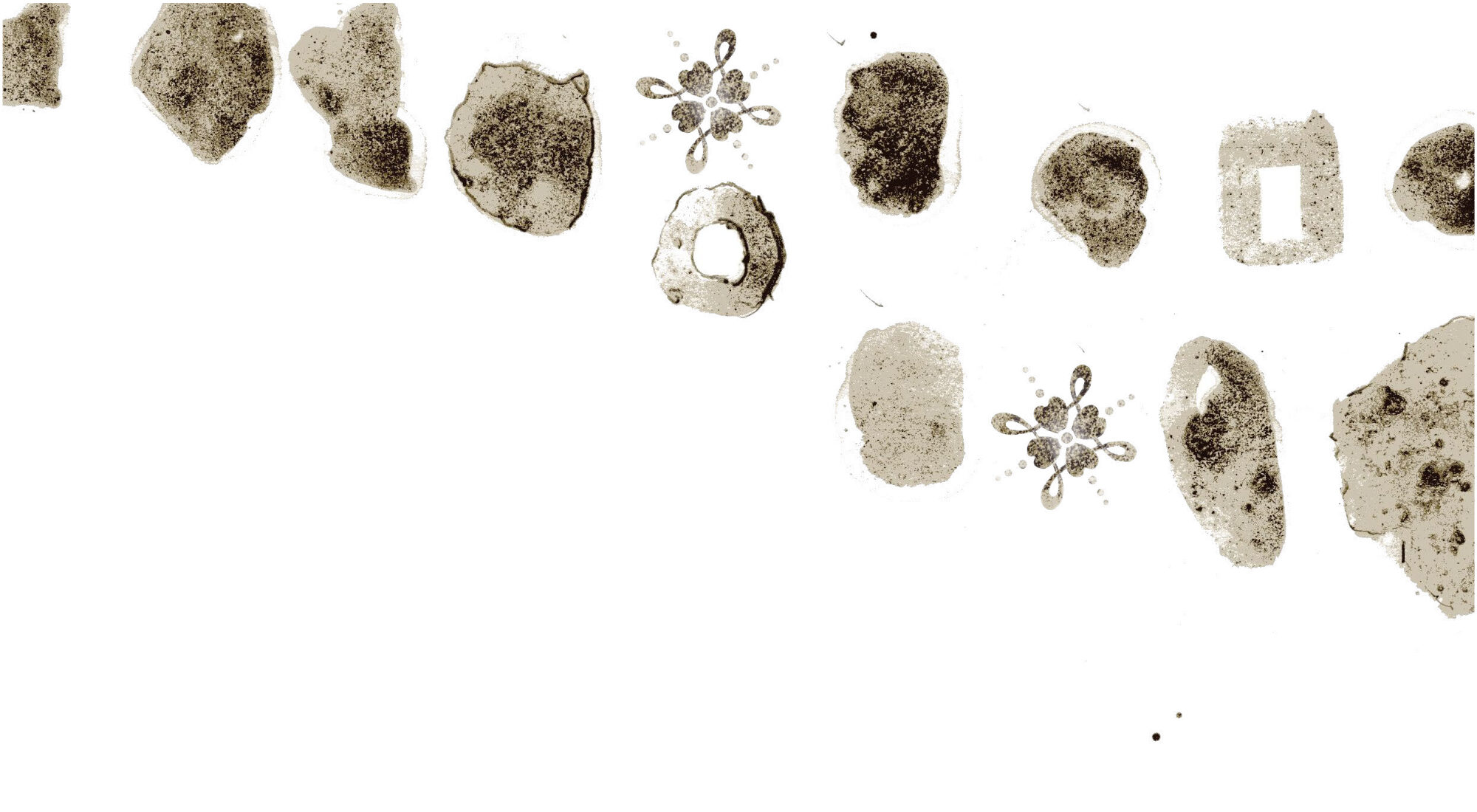

NET aims to put the traumatic experiences in the context and chronology of a person’s life. All that is needed is a rope, flowers and rocks in different shapes and sizes. During NET the patient, together with the counsellor/therapist, uses the rope to symbolize the lifeline of the individual, starting with the day he or she was born and ending at the present day. The end of the rope is rolled up representing the future of the individual. Alongside the lifeline the patient places flowers and rocks. The flowers symbolize positive or happy events in one’s life and the rocks symbolize distressing or traumatic events. Each event is given a title and date of occurrence. Taken together, this lifeline with the flowers and rocks gives a clear symbolic overview of what a person has experienced in his or her life.

This method offers the patient an overview of the chronology and the context which is helpful in overcoming upsetting memories. The first session is dedicated to putting down the lifeline, with in the following sessions the detailed discussion of the identified rocks and flowers. Especially the traumatic events are discussed in detail, such as the emotions, thoughts, physical reactions and details of the context in which the events happened. This trauma-exposure helps the person to overcome his/her fears that are part of the memories and over time helps the client to overcome his/her current traumatic symptoms. All events are written down by the counsellor which offers the client a full story of what he/she has been through. This creates a narrative of a person’s life, matching the cultural values of storytelling or oral traditions.

The NET treatment lasts between 8-12 sessions depending on the number of traumatic events a person has experienced. A session lasts around 90 minutes and can be done with a trained translator. This trauma focused therapy can result in a temporary increase in memories and fears during the treatment as part of the recovery process. In most cases, people report a reduction in PTSD symptoms during or immediately after the NET. The full recovery of PTSD symptoms happens in the period after therapy, where improvements of mental health issues can be observed 6-12 months after therapy (Neuner et al., 2010 & 2008b).

In Northern Uganda we as expat psychologists offered a 4-week training course to local lay counsellors in NET (Ghafoerkhan R & Hoogstad M, 2014; Neuner et al., 2008b). After this training they received further on-the-job-training and regular clinical supervision on the NET treatment they offered.

In our work we followed the international guidelines on mental health and psychosocial support services in emergency setting (IASC, 2007). In order to build adequate and long-term mental health resources in a post-conflict setting these guidelines also emphasize the importance of working closely with other organizations and local government within a referral structure.

Based on our experience in the field we have seen that Narrative Exposure Therapy is an effective and valuable tool. NET has proven to be a useful method for newly trained counsellors in treating people suffering from psycho-trauma related symptoms by reducing their PTSD symptoms and improving their overall mental health status.

* Name has been adjusted to ensure client’s privacy

References

- Catani C, Kohiladevy M, Ruf M, Schauer E, Elbert T & Neuner F (2009). Treating children traumatized by war and tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation relaxation in north-east Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 9, 22.

- Ghafoerkhan R & Hoogstad M. NET vanuit de bakermat: Uganda. Ervaringen uit de praktijk. In: Jongedijk R A. Levensverhalen en psychotrauma. Narratieve Exposure Therapie in theorie en praktijk. Uitgeverij Boom, Amsterdam (2014).

- Neuner F, Catani C, Ruf M, Schauer E, Schauer M, & Elbert T (2008a). Narrative exposure therapy for the treatment of traumatized children and adolescents. (KIDNET): From neurocognitive theory to field intervention. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 17, 641-664.

- Neuner F, Kurreck S, Ruf M, Odenwald M, Elbert T, & Schauer M (2010). Can asylum-seekers with posttraumatic stress disorder be succesfully treated? A randomized controlled pilot study. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 39, 81-91.

- Neuner F, Onyut P, Ertl V, Schauer E, Odenwald M & Elbert T (2008b). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder by trained lay counsellors in an African refugee settlement: A randomized control trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 76, 686-694.

- Neuner F, Schauer M, Klaschik C, Karunakara U & Elbert T (2004). A comparison of narrative exposure therapy, supportive counselling, and psychoeducation for treating posttraumatic stress disorder in an African refugee settlement. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72, 579-587.

- Ruf M, Schauer M, Neuner F, Catani C, Schauer E & Elbert T (2010). Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year olds: A randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23, 437-445.

- Schaal S, Elbert T & Schauer M (2011). Narrative exposure therapy versus interpersonal psychotherapy: A pilot randomized controlled trial with Rwandan genocide orphans. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 78, 298-306.

- Schauer M, Neuner F, Elbert T (2011). Narrative Exposure Therapy: A short Term Treatment For Traumatic Stress Disorders (2nd edition). Göttingen: Hogrefe Publishing.