Main content

Setting

This case is set in Paam Laafi, a small hospital at the edge of Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso. This hospital provides mostly primary care and has 2 medical doctors and 9 beds in the ward. It has a basic laboratory and a possibility to perform ultrasounds by a radiologist once a week. It is possible to refer patients to a bigger hospital in the capital, but these are almost always full and cannot provide enough care for most patients.

| Case A 19-year-old man with no prior history of disease presents with general malaise, a fever and progressive pain in his lower legs in the last 4 weeks. Furthermore, he has a headache, is mildly short of breath on exertion, and has a mild stomach ache. He has been vomiting after the consumption of food and has pain on passing urine. For 3 days, he has been unable to walk because of the pain. The patient says he has been working in Ivory Coast as a gold digger for the last 15 months. He received various treatments there including metronidazole injections, ciprofloxacin, tinidazol, anti-malaria treatment, metopimazine for nausea and unknown medication for the cough and the stomach ache. These had no effect, and he is now back in Burkina Faso for medical consultation. |

Physical examination

On physical examination he looks ill. The vital signs show a pulse rate of 108 beats per minute and a temperature of 40 0C. The blood pressure cannot be measured because of lack of a working device. The SpO2 is normal. Examination of the heart, lungs and abdomen and skin is normal. The legs look symmetrically normal on inspection; palpation of the lower legs and especially the soles of the feet is symmetrically very painful. The muscle tone is normal, as is the temperature of both legs.

Neurological examination of the legs shows an intact distinction between cold and warm objects, as well as normal vibration sense, but he could not differentiate between blunt and sharp objects. The muscle power and gait could not be tested because of the pain.

In the following two weeks, multiple additional tests were performed. An ultrasound of the abdomen showed a bilateral microlithiasis of the kidneys and a splenomegaly.

Laboratory investigations showed a haemoglobin level of 7.6 mmol/L; there was a thrombocytosis of 547 x 109/L and a mild hyponatraemia of 129 mmol/L. CRP, leukocytes, potassium, liver function tests, glucose and creatinine were all normal. The urine culture showed no growth of bacteria. A CT-scan of the brain was performed in a private clinic which showed no abnormalities. HIV and malaria tests were both negative. The medical doctors in charge could not make a clear diagnosis and asked our specialist panel for help. In the meantime, the patient was admitted to the ward and received paracetamol and vitamin B1, B6 and B12.

Specialist advice

The specialist panel suggested an extensive list of differential diagnoses, which are summarized in 3 groups:

- Neuropathy, triggered by intoxication (alcohol, drugs, botulism, exposure to toxin such as arsenic, acrylamide, mercury [Hg]) or by deficiency (vitamin B1, B6, B12 {subacute combined neuropathy}).

- Vascular causes, including vasculitis, arterial obstruction or thrombosis. Since a more extensive physical examination showed no explicit signs for this, these seemed less likely.

- Infection of unknown origin, although this was considered less likely, considering the low CRP and leukocytes. There were no signs of leprosy; the tests for HIV and malaria were negative.CRP and leukocytes. There were no signs of leprosy; the tests for HIV and malaria were negative.

Because of the history and physical examination, neuropathy seemed most likely. Electromyography for a definitive diagnose was not possible. As happens so often in clinical practice in a resource-limited setting, no final diagnosis could be established.

However, for teaching purposes we discuss the clinical features of mercury (Hg) intoxication, as he had been working as a gold digger, and to emphasize the importance of inquiring about occupational exposure.

Mercury intoxication

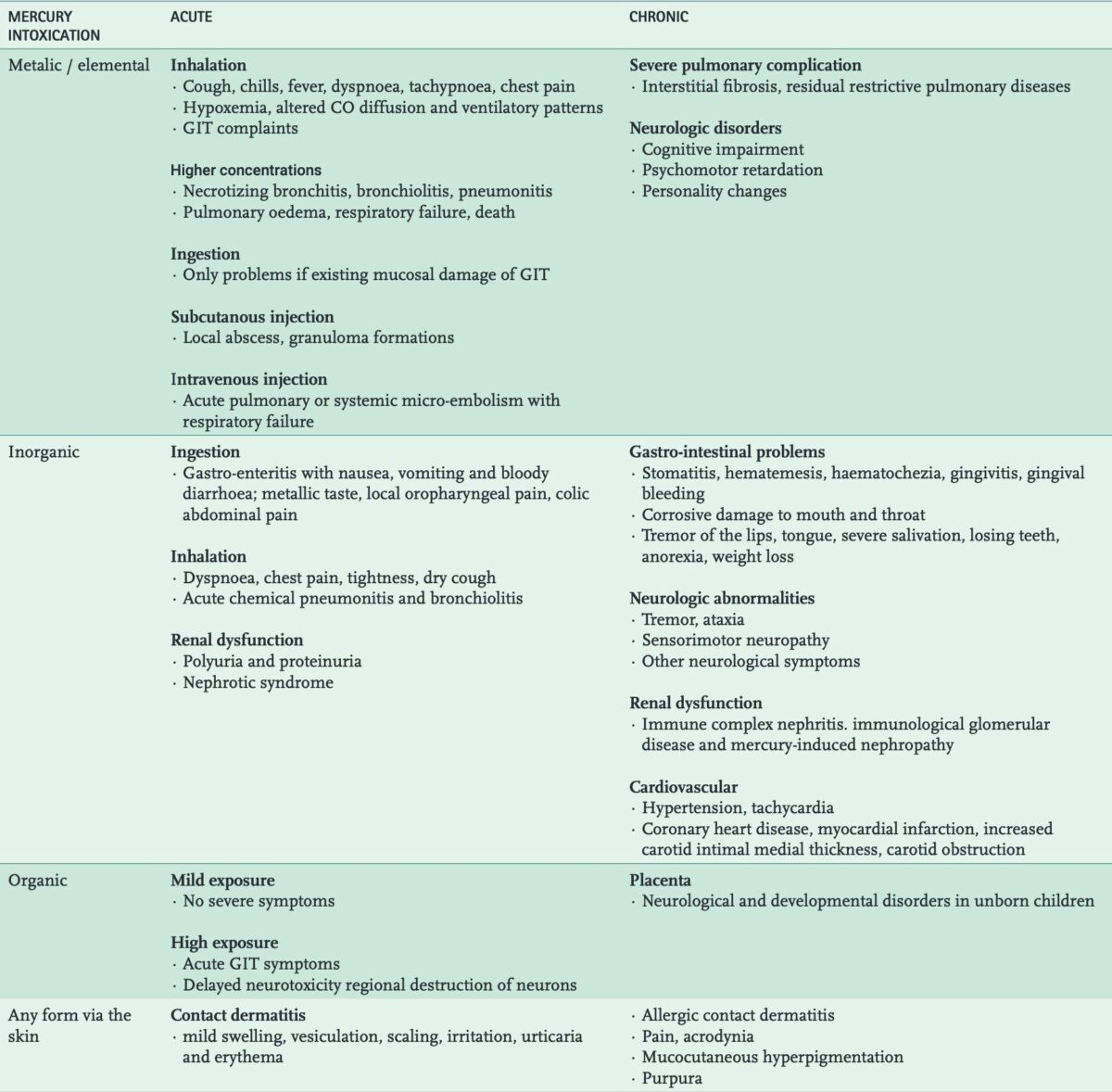

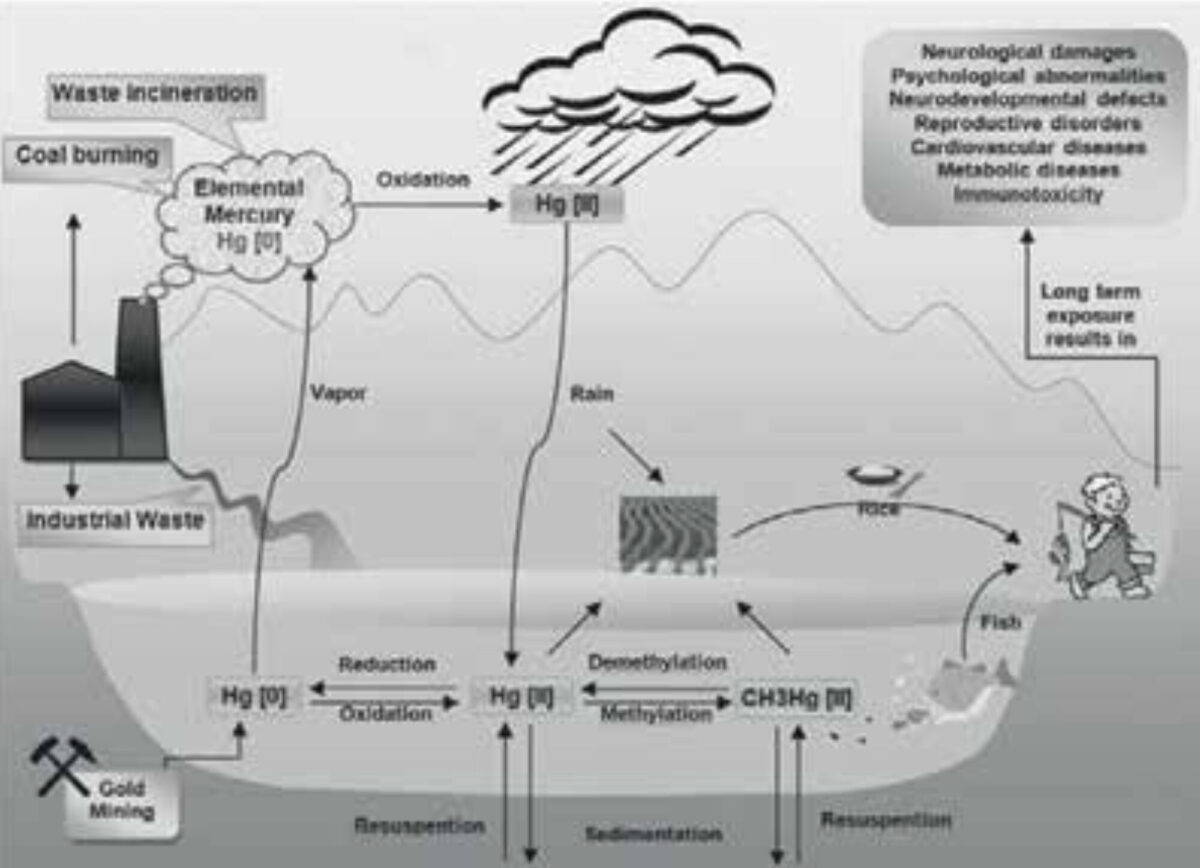

Mercury (Hg) has long been admired by humans, as it is not only attractively bright but also the only metal that remains fluid at room temperature. However, mercury is very toxic and may affect many organ systems, including skin, nervous system, cardiovascular, musculoskeletal, genitourinary, and respiratory systems. This broad and non-specific presentation may make it difficult to diagnose a mercury intoxication. [1,2] Since mercury is used for extracting gold, there is a serious risk for mine workers of developing an intoxication. There is also a possible risk of exposure via tooth fillings, vaccines, or eating seafood because of mercury accumulation in fish and shellfish. [3] The chemical form, dosage and duration of exposure to mercury determine the profile of toxicity. [1,4] The different forms are elemental or metallic (Hg o), inorganic (Hg II) and organic (CH3Hg II) compounds. [1-4] See Figure 1 for an overview of mercury in the environment. The most important clinical features of mercury intoxication are summarized in Table 1.

Diagnosis and treatment

Measurement of mercury (concentrations) is possible in plasma, urine, stool and even hair samples. Again, the form of mercury determines the sample: urine for elemental or inorganic mercury, but stool for organic mercury (e.g. methyl mercury). [2]

Treatment is mainly supportive, [1,2,4] and activated coal can be used after acute ingestion. [1] Mercury-specific chelating agents are D-penicillamine (DPCN), dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), 2,3-dimer captopropane-1-sulfonate (DMPS), and dimercaprol (British Anti-Lewisite; BAL). [1, 2, 3] It is important, given the side-effects of these drugs, for the Hg intoxication to be confirmed. [3] Lastly, prevention of exposure to Hg in the environment is of paramount importance. [4]

Follow up

The patient was admitted, and after 5 days the body temperature normalized and the pain in his legs was almost gone. He kept having poor appetite and vomited after the consumption of food. A gastroscopy was performed and pangastritis with gastroparesis was visible. The specialist indicated this could be part of a combination autonomic/peripheral neuropathy and advised erythromycin. The patient left the hospital feeling better after 1 week. Later biopsies of the stomach showed evidence of H. pylori infection but no atrophic cells. At follow-up one year later, he was well and asymptomatic. He did not return to Ivory Coast to work as a gold digger.

Contact: c/o MTredactie@nvtg.org

References

- Yildiz M, Adrovic A, Gurup A, et al. Mercury intoxication resembling pediatric rheumatic diseases: case series and literature review. Rheumatol Int. 2020 Aug;40(8):1333-1342. doi: 10.1007/s00296-020-04589-2. Epub 2020 Apr 27. PMID: 32342181.

- Rafati-Rahimzadeh M, Rafati-Rahimzadeh M, Kazemi S, Moghadamnia AA. Current approaches of the management of mercury poisoning: need of the hour. DARU J Pharm Sci 22, 46 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2008-2231-22-46

- Boscolo M, Antonucci S, Volpe AR, et al. Acute mercury intoxication and use of chelating agents. J Biol Regul Homeost Agents. 2009 Oct-Dec;23(4):217-23. PMID: 20003760.

- Bensefa-Colas L, Andujar P, Descatha A. Intoxication par le mercure [Mercury poisoning]. Rev Med Interne. 2011 Jul;32(7):416-24. French. doi: 10.1016/j.revmed.2009.08.024.