Main content

History

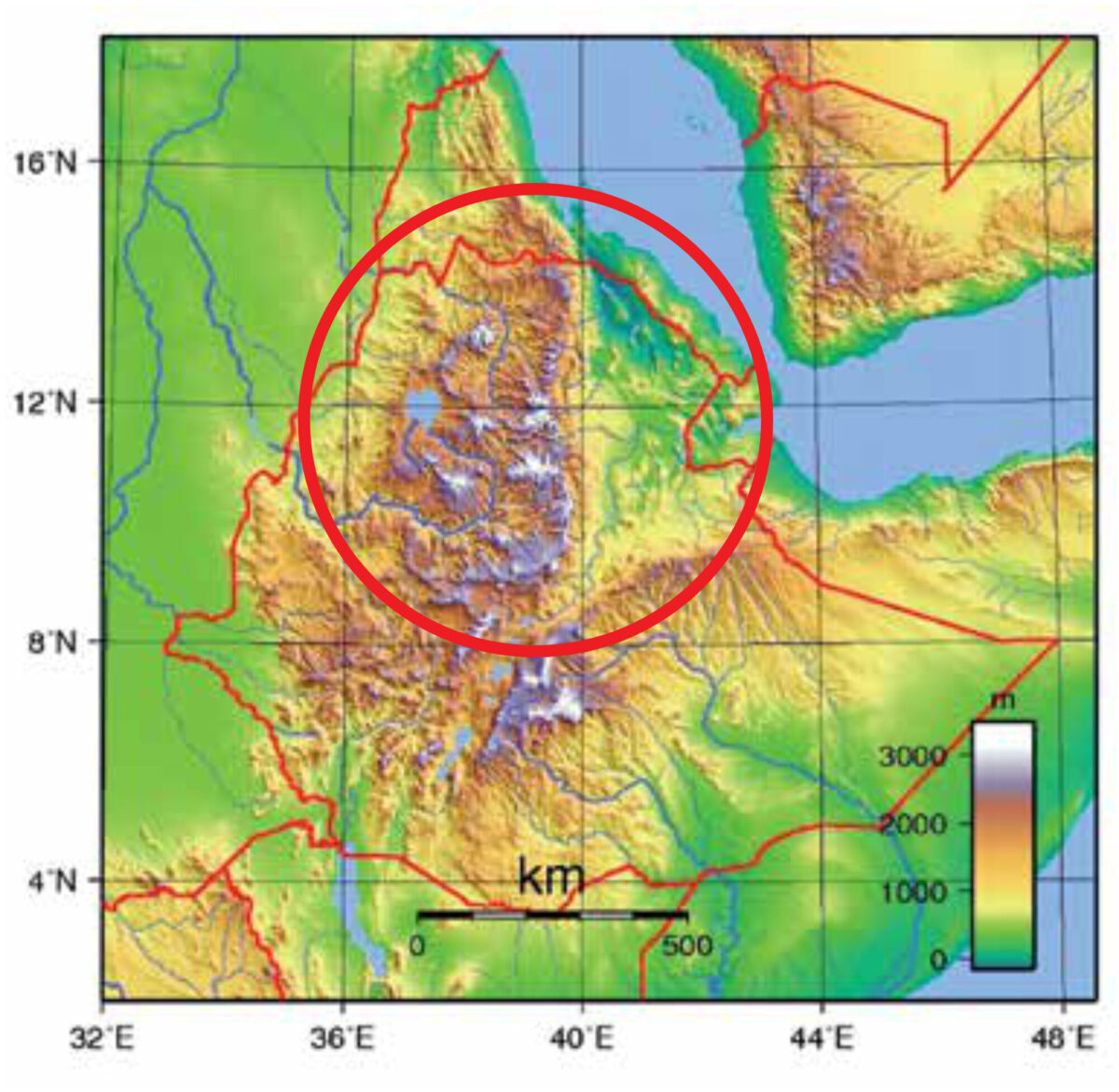

A 24-year-old farmer presents to your clinic in the Amhara Region of Northwest Ethiopia (Figure 1). Не complains of progressive swelling of the feet over the last eight years with a burning sensation, and develop-ment of firm nodules particularly on the toes, that were increasingly itchy.

Further history and previous medical history are unremark-able. He has lived his whole life in the area and did not travel.

above sea level.

Setting

Your clinic is in a remote area at a height of 2,600 meter, with an outpa-tient department, two general wards with twenty beds, and a maternity ward. It has a basic laboratory where basic haematology, urine, malaria tests, stool for parasites, sputum for acid-fast bacilli (AFBs) and an HIV test can be done; there is an X-ray machine and ultrasound scans can be performed. Medication for the most prevalent diseases is available, as well as vaccines for the EPI programme. Supplies come usually every two weeks from the nearest regional hospital, one day’s driving away. Blood and other material for specific tests can be sent to the regional laboratory.

Clinical findings

On examination, he is well with normal vital signs. No abnormalities are found on examining head and neck, chest, and abdomen. The only abnormalities are found on the legs; there was non-pitting oedema, and the skin feels rough on palpation. There are multiple medium to large sized nodules that are fixed to the skin and firm on palpation. There are multiple bilateral palpable lymph nodes in the legs and in the inguinal area.

the toes.

Laboratory results

Normal haematological para-meters. HIV test: non-reactive.

| Question 1 a. Consider the following differential diagnoses, and give the main characteristics of each of the differential diagnoses listed: * filarial lymphoedema * Kaposi’s sarcoma (‘classic type’) * leprosy * podoconiosis * mycetoma (Madura foot) * Milroy’s disease * longstanding oedema due to cardiovascular disease * myxoedema * chromoblastomycosis b. What is the most likely diagnosis given the clinical picture and geographical epidemiology? Question 2 Question 3 |

Answers to question 1

(a. Give the main char-acteristics of each dif-ferential diagnosis.)

(b. What is then the likely diagnosis given the clinical picture and geographi-cal epidemiology?)

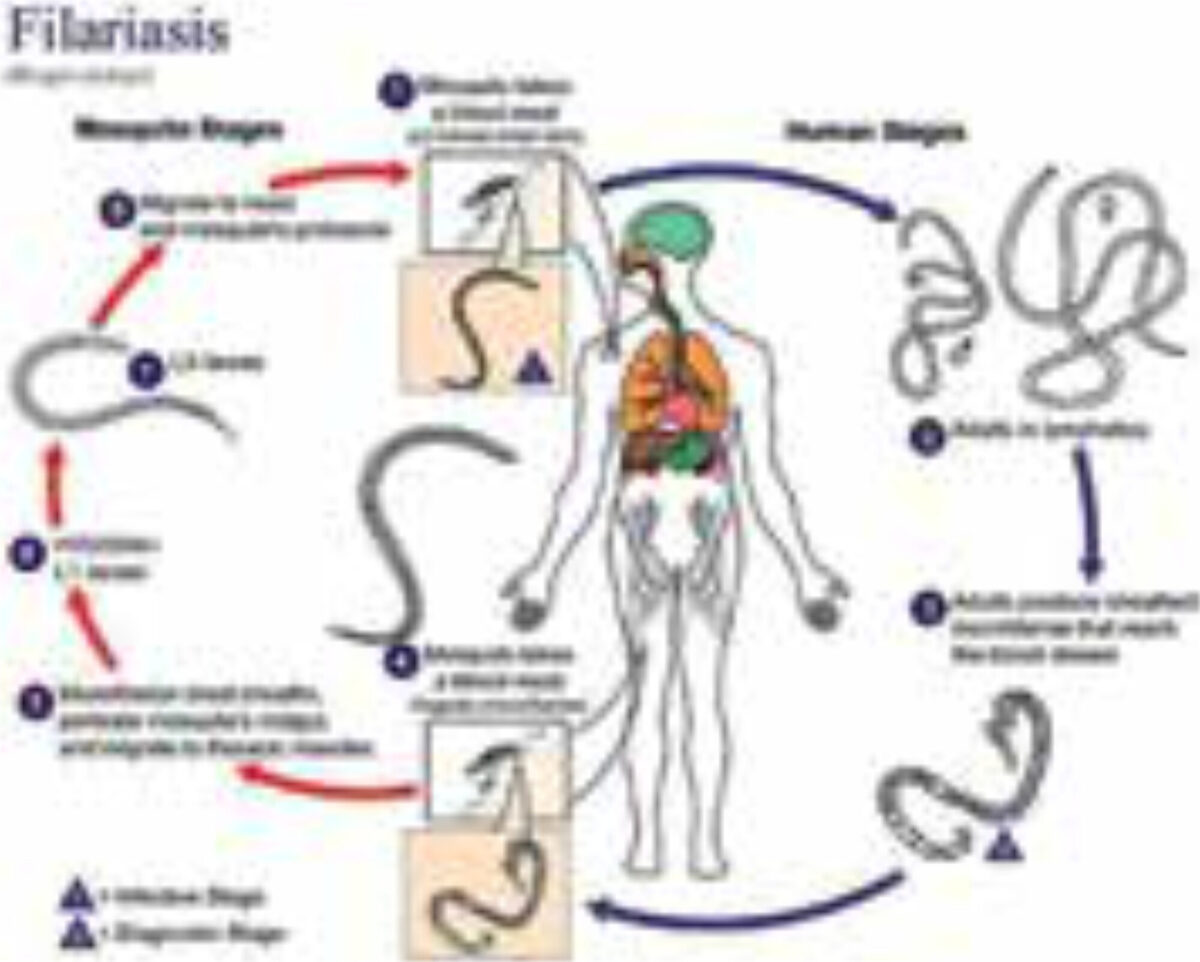

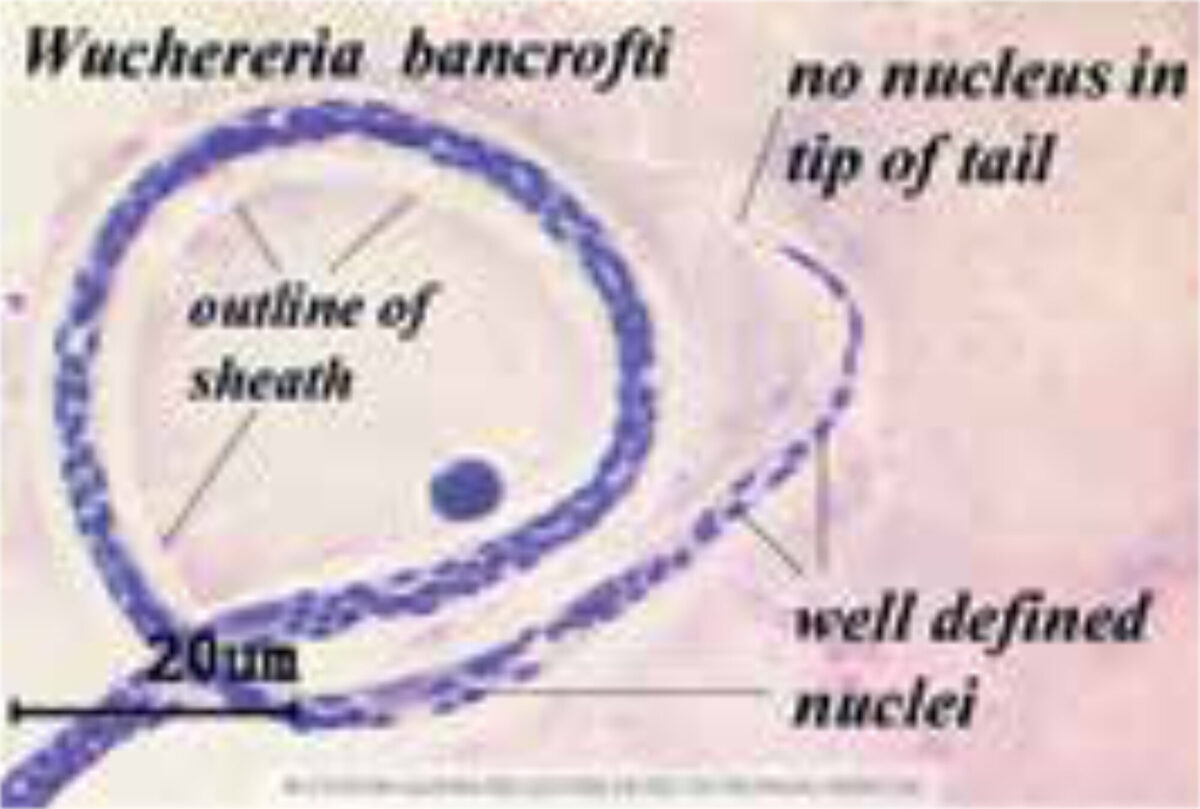

Filarial lymphoe-dema (figure 3 a-e)

There are three important manifestations of filarial disease: onchocerciasis, lymphatic filariasis (LF) and loiasis. This region is endemic for LF only. In LF, the microfilaria is transmitted by a Culex mosquito. Wuchereria bancrofti is the most important filarial species. The adult worms lodge in the lymphat-ics usually in the inguinal area causing obstruction of lymphatic flow leading to chronic lymphoedema. Subsequent severe swelling causes cracks in the skin and secondary bacterial infection that aggravate the swelling, discom-fort, and disability. Similar giant swelling may occur in the scrotum. Treatment is with antiparasitic drugs and skin hygiene to reduce infection.

Kaposi’s sarcoma (hiv related, or the ‘classic type’) (figure 4 a, b)

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) is very common across Africa in the context of HIV infection. It is a World Health Organization Clinical stage 4 condition and occurs in patients with very low CD4 counts <200 cells/mm³. It is caused by human herpesvirus (HHV) 8. In addition to a positive HIV test, one would look for KS in other sites such as the buccal mucosa, and other parts of the skin. Treatment is with chemotherapy and antiretroviral therapy.

In addition, KS may present as the clas-sical type that affects elderly men and that runs an indolent course. Here, the patient is HIV negative. The classic type is usually present in middle aged and older men. It is uncommon in Ethiopia.

Leprosy (figure 5 a-c)

Leprosy is caused by Mycobacterium leprae and leads to a spectrum of clinical manifestations. Transmission is principally from mother-to-child during nursing. The bacilli can be demonstrated by microscopy in scrap-ings or by PCR. On one end of the spectrum, where the immune response is strong, is tuberculoid leprosy – these patients have a relatively low bacillary load (paucibacillary leprosy) with severe destruction of tissues; on the other end of the spectrum is lepromatous leprosy with a weak immune response – these patients harbour high numbers of bacilli (multibacillary leprosy); there is local spread but little necrosis. Sensory loss is an important feature (absent in this patient). Treatment is with anti-leprosy drugs. Leprosy control efforts have been successful due to concerted efforts over the last six decades; in Ethiopia, new leprosy cases have now dropped from 80,000 in 1985 to 3,000 in 2016. With waning interest by national control programmes, transmission is ongoing, and new cases continue to appear.

of previous surgery.

Visser)

Podoconiosis (figure 6,7)

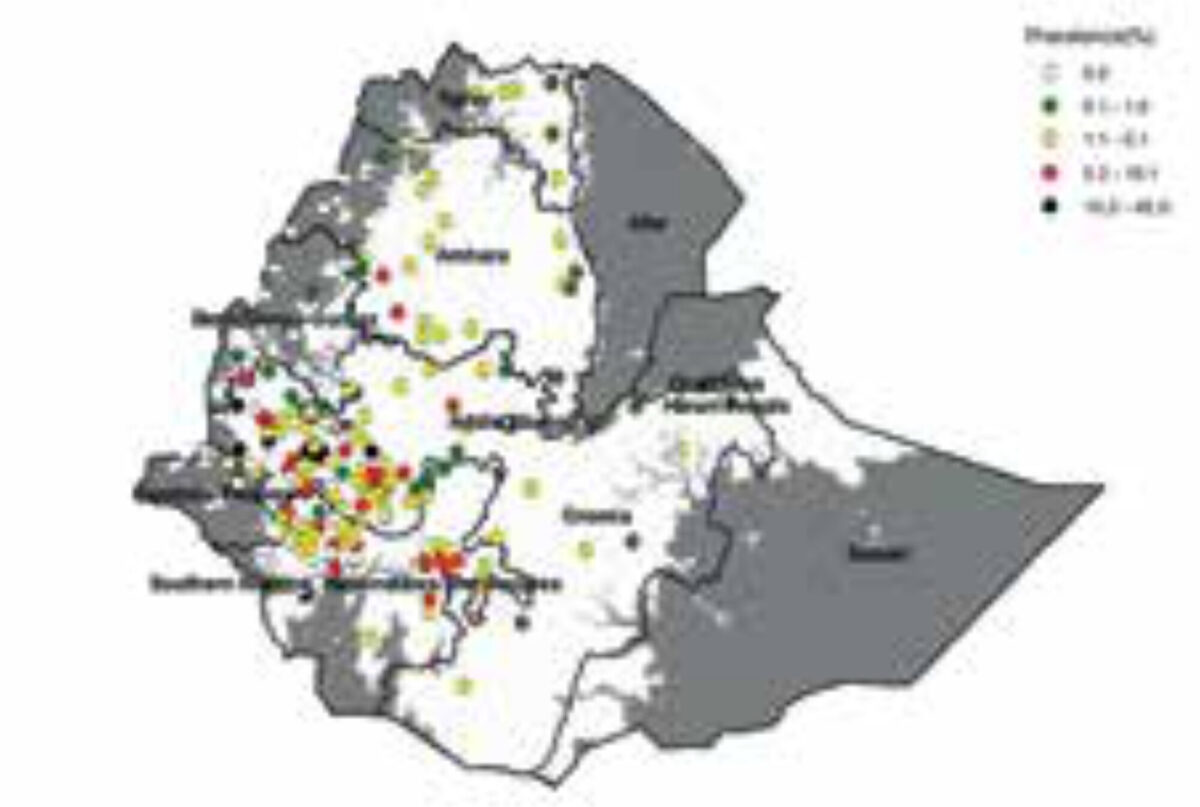

The name is derived from the Greek podos (foot) and konos (dust). It is also known as tropical elephantiasis, endemic non-filarial elephantiasis, mossy foot disease, microcrystal disease, big foot disease or lympho-static verrucosis. It is distinct from LF; it is a non-communicable disease. It has a worldwide distribution and is common in Ethiopia. An estimated 1 million people are affected in Ethiopia, and 0.5 million in Cameroon.

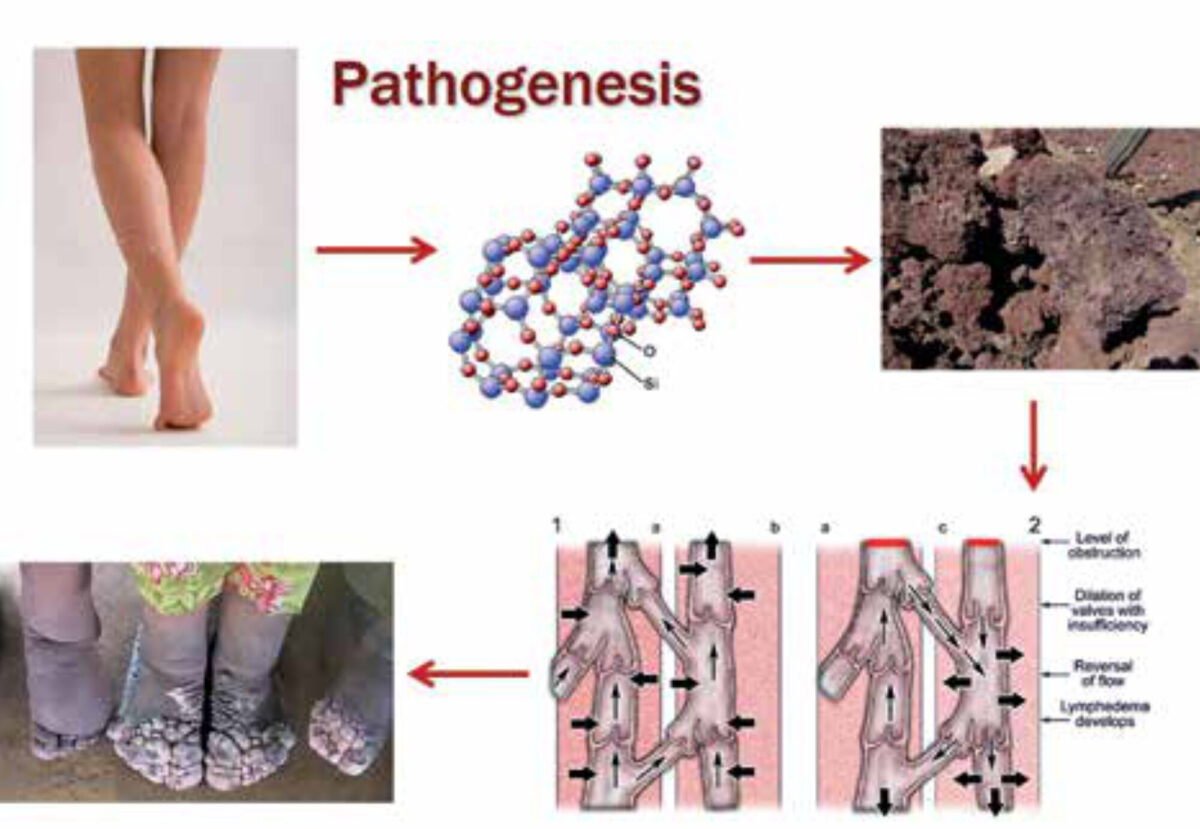

Clinically it is characterised by ascend-ing, commonly bilateral but asym-metric, lymphoedema. It is caused by exposure to irritant soils, usually red clay soil near volcanoes. Tiny micro particles of silica from the volcanic soil and aluminosilicates penetrate the skin. There is 5-10% prevalence in areas of irritant soil and subsistence farming.

In the prodromal phase, there may be itching, burning, splaying of forefeet and ‘block toes’ occur, followed by plan-tar oedema and hyperkeratosis. This is followed by soft ‘water bag’ type swelling or hard fibrotic, ‘leathery’ type swelling, associated with multiple skin nodules.

This is the most likely diagnosis, because of the geography and history of the patient who walks and works on bare feet. He presents with an ascending clinical course in the leg, starting in the feet, progressing to the knee, and rarely affecting upper leg or groin. It is bilateral yet asymmet-ric. Podoconiosis occurs at an altitude of ≥1,500 meter (where there is no filarial transmission). However, filarial lymphoedema needs to be excluded anyway in this context as the treatment would require anti-filarial drugs.

podoconiosis in Ethiopia. (Courtesy Dr JB Visser)

Answer to question 2

(What additional investiga-tions would you like to do to establish the likely diagnosis?)

In vitro immunodiagnostic assay for the detection of W. bancrofti antigen; this comes back as ‘negative’. Together with the clinical picture and the fact he had stayed life-long in the area, podoconiosis is the most likely diagnosis.

Answer to question 3

(How would you manage the patient?)

The main issues are:

Treatment (figure 8)

- There is no specific treatment.

- Foot hygiene with soap, antiseptics ointment, pressure bandages, and wearing socks and shoes are effective in reducing the stage of disease, with reduction of leg circumference and improved quality of life (Figure 6)

- Occasionally nodulectomy is indicated

- Social rehabilitation

Prevention

- Awareness in endemic areas; there are few dedicated disease control programmes worldwide

- Community education, reducing stigma

- Providing shoes free of charge

Eliminate because of the following

- Entirely preventable disease ‘Prevent Podoconiosis, Wear Shoes’;

- Large window of opportunity (10 years of persistent contact before symptoms start to appear)

- Non-communicable disease (no human carrier, no flying vector or animal reservoir);

- Easy detection (clinically distinguishable from LF)

- Exists only in localized regions with specific climatic criteria

- Management synergy with other NTDs

How is the ethiopian farmer doing?

He has almost fully recovered after intensive secondary prevention, and has found a new job as an orthopaedic shoe-maker providing tailor-made shoes for patients with podoconiosis (Figure 9).

Discussion of the other differential diagnoses

Mycetoma (madura foot) (figure 10)

Mycetoma may be caused by bacteria (actinomycetoma) or fungi (eumyce-toma). It has a worldwide distribution with actinomycetoma being most common in Mexico and eumycetoma in Sudan. This is an infection by implantation; the organism enters through the skin usually on the foot in people who do not wear shoes. There is a clinical triad: swelling, sinuses, and expulsion of grains. The disease leads to severe morbidity and stigma; it affects mainly young adults. Treatment is with antibiotics or antifungals.

Milroy’s disease

This is a very rare hereditary condi-tion that is characterised by congenital abnormalities of the lymphatic sys-tem, usually leading to unilateral lower extremity lymphoedema.

Longstanding oedema due to cardiovascular disease

This is a form of bilateral ankle oedema ascending to the lower and upper leg in severe cases. It is typically pitting oedema, but in longstanding cases the oedema may become indurated. Clinically one looks for symptoms and signs of heart failure; underlying heart disease may be post-myocarditis, alcoholic cardiomyopathy, hypertensive cardiomyopathy, or rheumatic heart disease. Ischemic heart disease is uncommon in most parts of Africa.

Myxoedema in thyroid disease (figure 11)

This is a feature in auto-immune thyroid disease. Clinically, patients may have hyper- or hypothyroidism; in others the thyroid function may be normal.

Chromoblastomycosis (figure 12)

Chromoblastomycosis is a chronic fun-gal infection of the skin and subcutane-ous tissue, most commonly of hands, feet and lower legs. It is typically caused by traumatic percutaneous inocula-tion of the fungal genera Fonsecea, Phialophora and Cladophialophora, which are found in plant debris or tropical detritus. Infection ocurs worldwide but is most common in rural (sub)tropical areas. Male agricultural workers are most commonly affected.

Painless lesions develop slowly over years from the site of inoculation as verruccous nodules or plaques, gradu-ally spreading centripetally by lymphatic or cutaneous dissemination. Typical complications are ulcerations, chronic lymphoedema, and even elephantia-sis and bacterial superinfection. Diagnosis is made by direct micro-scopic detection of pathognomonic sclerotic cells in skin scrapings on a simple wet film; hyphae are seen on a potassium hydroxide preparation. More sophisticated techniques (e.g. culture, serology, PCR) are rarely avail-able in endemic areas. Infection is not life-threatening (unless in immune-supressed patients), but is difficult to treat (long-standing therapy, usu-ally combination of anti-fungals).

Here, history and clinical picture of the patient could well fit with the descrip-tion of chromoblastomycosis. However, the geographical epidemiology (height, typical soil) makes it less likely, but above mentioned simple microscopic examination should not be left out.

Chromoblastomycosis.htm (reproduced with permisson of Dr JR Mekkes).