Main content

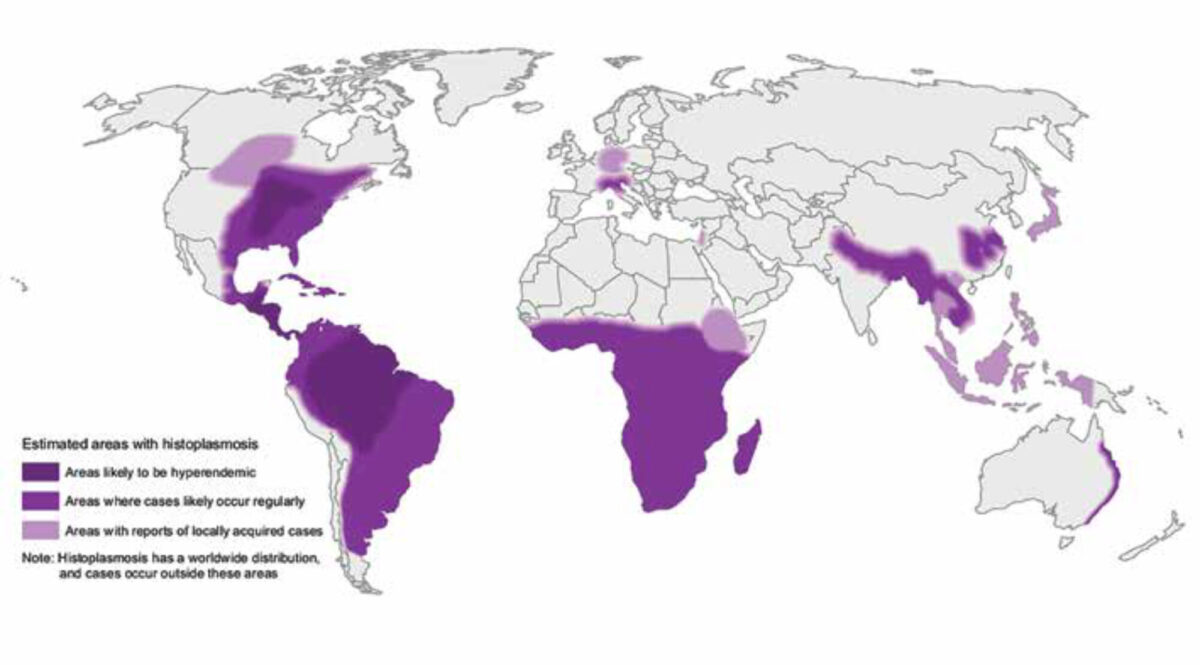

Histoplasmosis is caused by the fungus Histoplasma capsulatum. Inhala-tion of spores causes the infection, which occurs especially in people disturbing soil that contains bird or bat droppings, but is also reported in travellers after visiting caves or guanos.[1,2] After inhalation, the body temperature transforms the spores into yeast cells which in turn spread to lymph nodes and the bloodstream. Histoplasmosis does not spread between people and animals or between infected people. H. capsulatum and its vari-ants are distributed throughout the world, especially in the Americas, followed by Africa, Asia and Aus-tralia. H. capsulatum var. duboisii is the larger uncommon African variant causing extrapulmonary manifestations but treated similarly (Figure 1).

The true incidence of histoplasmo-sis is difficult to determine, but the majority of cases occur in North and Latin America, with around 6.1 cases per 100,000, and even outnumbering the deaths from tuberculosis. Although in Italy there have been some endemic cases, histoplasmosis is extremely rare in Europe and is mainly imported by migrants and travellers. Hence, most (European) physicians are unfamil-iar with this disease. The difference in geographic distribution is caused by variations in soil composition (vegetation) and climate.[3,4] Although the period of incubation ranges from three to seventeen days, diagnosis has been described up to forty years after exposure in an endemic region.[5] Quite similar to Mycobacterium tuberculo-sis, and often difficult to distinguish, H. capsulatum can remain in a qui-escent state until the cell-mediated immunity is compromised.[6]

Global burden of histoplasmosis

In 2017 the World Health Organization broadened the list of neglected tropical diseases with deep mycoses, of which histoplasmosis is one. Despite its ende-micity, the global burden of histoplas-mosis is not well documented. It was Charles Darwin who first described histoplasmosis in the Panama Canal Zone in 1906, reporting patients with features of disseminated tuberculosis. Nowadays, the spread of HIV together with the increasing use of immunosup-pressive drugs, for example in chronic inflammatory diseases or after organ transplantation, are major risk factors for histoplasmosis. Already in 1987, disseminated histoplasmosis was clas-sified as an AIDS-defining infection, but histoplasmosis still remains as under-recognized and misdiagnosed as tuberculosis. Historically, prevalence mainly manifested itself in North and South America. However, in the African continent, the incidence of histoplas-mosis increases with the burden of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. However, both diagnosis and treatment are difficult because of costs and lack of materials or trained personnel. Worryingly, intrave-nous amphotericin B, the first-choice antifungal therapy in disseminated disease, is not licensed or is unavailable in a number of African countries.[7]

Clinical presentation, diagnosis, treatment and prevention

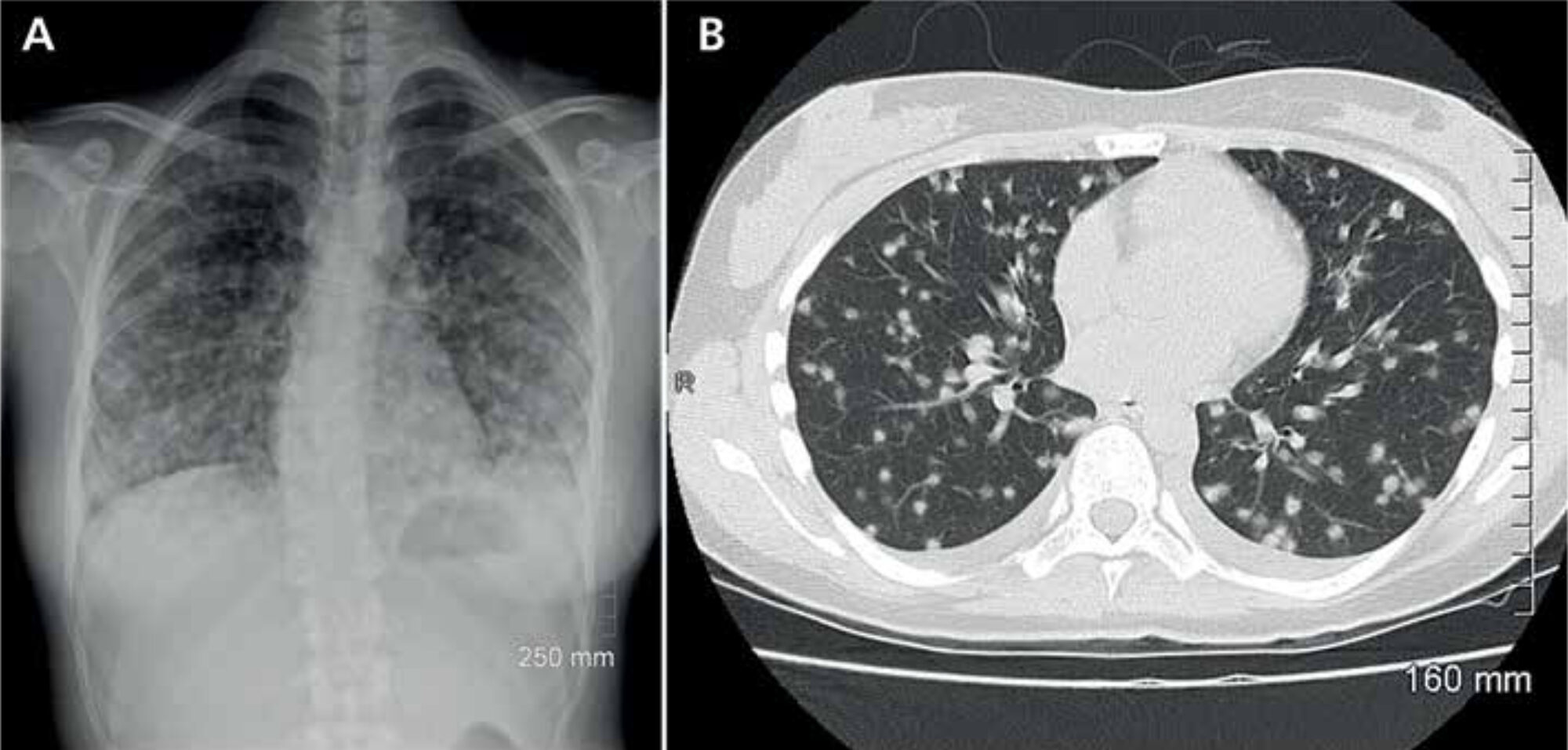

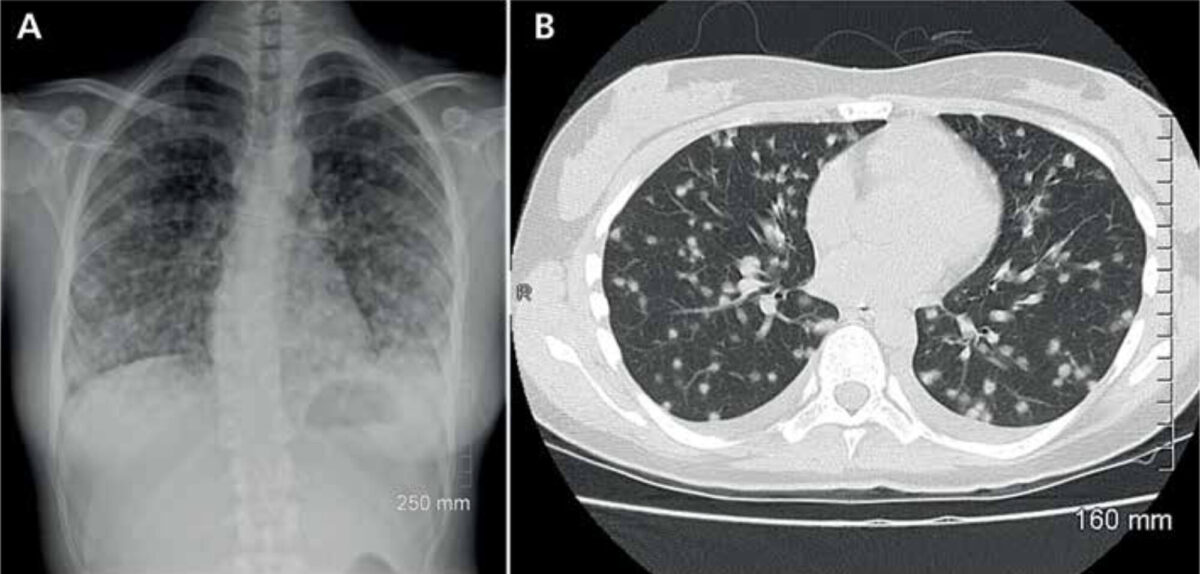

In most patients, infection is asymp-tomatic, but it may lead to disseminated histoplasmosis, a life-threatening ill-ness. Upon infection, patients usually present themselves with pulmonary complaints (Figure 2). A more general presentation with malaise, fever, myal-gia, rheumatic manifestations or even central nervous system histoplasmosis may occur. Diagnosis is confirmed by a positive culture or, more rapidly, by antibody or antigen testing.[6] Because histoplasmosis is known to mimic other diseases, the risk of exposure is an important clue to raise the index of suspicion. The recently published systematic review by Antinori et al. described that progressive dissemina-tion was mostly seen in HIV positive patients, but that the worst outcomes were seen in HIV negative immuno-compromised subjects, with a mortality rate of 32%.[5] Treatment options include intravenous amphotericin B or oral itraconazole. The latter is recommended by the Infectious Diseases Society of America as prophylactic therapy in HIV positive patients in highly endemic areas. The duration of treatment depends on the severity of the disease.

Conclusion

Histoplasmosis is a neglected tropi-cal infection. Even outside of endemic regions it is important for physicians to recognize and manage this disease, particularly in view of the worldwide migration patterns and global travel.

References

- Staffolani S, Buonfrate D, Angheben A, et al. Acute histoplasmosis in immunocompetent travelers: a systematic review of literature. BMC Infect Dis. 2018 Dec 18;18(1):673. doi: 10.1186/s12879-018-3476-z.

- Ariaans M, Valladares MJ, Keuter M, et al. Fever and arthralgia after ‘volcano boarding’ in Nicaragua. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2017 Mar-Apr;16:68-9. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2017.02.005. Epub 2017 Feb 15

- Mittal J, Ponce MG, Gendlina I, et al. Histoplasma capsulatum: mechanisms for pathogenesis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2019;422:157-191. doi: 10.1007/82_2018_114

- CDC [Internet]. Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2021. National Center for Emerging and Zoonotic Infectious Disease (NCEZID); 2021 Sep 17. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncezid/

- Antinori S, Giacomelli A, Corbellino M, et al. Histoplasmosis diagnosed in Europe and Israel: a case report and systematic review of the literature from 2005 to 2020. J Fungi (Basel). 2021 Jun 14;7(6):481. doi: 10.3390/j0f7060481

- Linder KA, Kauffman CA. Histoplasmosis: epidemiology, diagnosis, and clinical Manifestations. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2019;13:120-28. Doi: 10.1007/s12281-019-00341-X

- Oladele RO, Ayanlowo OO, Richardson MD, et al. Histoplasmosis in Africa: an emerging or a neglected disease? PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2018 Jan 18;12(1):20006046. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0006046

- Ashraf N, Kubat R, Poplin V, et al. Re-drawing the maps for endemic mycoses. Mycopathologia. 2020 Oct;185(5):843-65. doi: 10.1007/s11046-020-00431-2