Main content

The Malawi HIV programme is considered a model for the public health approach to antiretroviral therapy (ART) in sub-Saharan Africa. It demonstrates that with government backing, support from (inter)national non-governmental stakeholders and adequate multilateral funding, the prognosis for people living with HIV can be improved dramatically. Mother-to-child transmission can be reduced to below 5% and HIV incidence can be reduced, despite severe socio-economic challenges and a health care system lacking sufficient trained staff. This article presents some examples of successes and several challenges.

Examples of malawi’s successful public health approach to art

In 2011, Malawi developed its own Option B+ strategy for the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT). Pregnant and breastfeeding women who test positive for HIV start their lifelong ART on the very same day (see text box on PMTCT options). This happens irrespective of their clinical condition and CD4 count. [2] This strategy was initially criticized, as there was no evidence of its effectiveness and due to ethical concerns about coercing women to start ART. [3] The Option B+ strategy led to a tremendous increase in access to PMTCT in Malawi. A national study has shown that over a period of seven years, mother-to-child HIV transmission was reduced to levels close to those seen in affluent settings. [4, 5] The Option B+ strategy has now become the preferred WHO policy for resource limited settings.

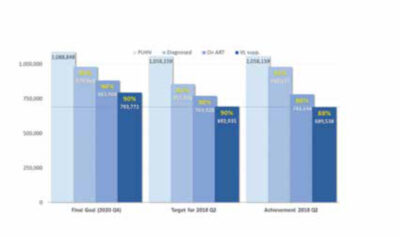

In 2016, in line with the new WHO treatment guidelines, the Malawi Government introduced universal ART eligibility for all people living with HIV, irrespective of their CD4 cell count and clinical stage of HIV disease. At present, the Malawi HIV programme is close to reaching the ambitious ’90-90-90′ UNAIDS treatment targets that aim to end the AIDS epidemic: 90% of people living with HIV (PLHIV) know their HIV status, 90% of diagnosed PLHIV are on sustained ART, and 90% of those on ART have a suppressed viral load (i.e. HIV-1 RNA <1,000 copies/mL), as shown in Figure 1. [6]

The total number of patients on ART in Malawi is currently about 800,000, representing close to 80% ART coverage in PLHIV. The survival benefit of ART on this scale has contributed to an increase in the life expectancy of the general population. [7] Such a large patient population requiring chronic care also places an enormous burden on the fragile health system. Simplified guidelines are needed to allow task shifting of the decision to start ART from physicians to non-physician clinicians and nurses.

In the Malawian public health approach, ART involves a limited number of standardized regimens. Initially, stavudine-lamivudine-nevirapine was the standardized first-line regimen. However, this caused frequent and severe side effects such as peripheral neuropathy, lactic acidosis, lipodystrophy due to stavudine, and severe hypersensitivity reactions due to nevirapine. [8, 9] Toxicities became much less common when this was replaced by tenofovir-lamivudine-efavirenz. Further improvement is expected with the planned introduction of a dolutegravir-based regimen in 2019. In case of failure on standardized first and second line ART regimens, Malawian PLHIV now have access to a third-line ART regimen, although very few patients are currently taking this.

Challenges in the malawi hiv programme

Despite the successes, a number of important challenges remain. First of all, sustainability of the programme cannot be taken for granted. The programme depends on donations, mostly from the United States (through PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. Second, the HIV programme is a vertical ‘silo’ in a country with a primary health care system that has much less financial support otherwise. Integration with other health services (family planning and hypertension clinics for instance) is limited. Third, patient attrition due to a combination of defaulting from treatment and death is considerable. In the national cohort that started ART eight years ago, only 50% of patients are still registered as ‘alive and on treatment’. [6] Further challenges include HIV drug resistance, lack of tailored care for key populations (adolescents, sex workers and men having sex with men), and numerous patients still presenting with advanced HIV disease.

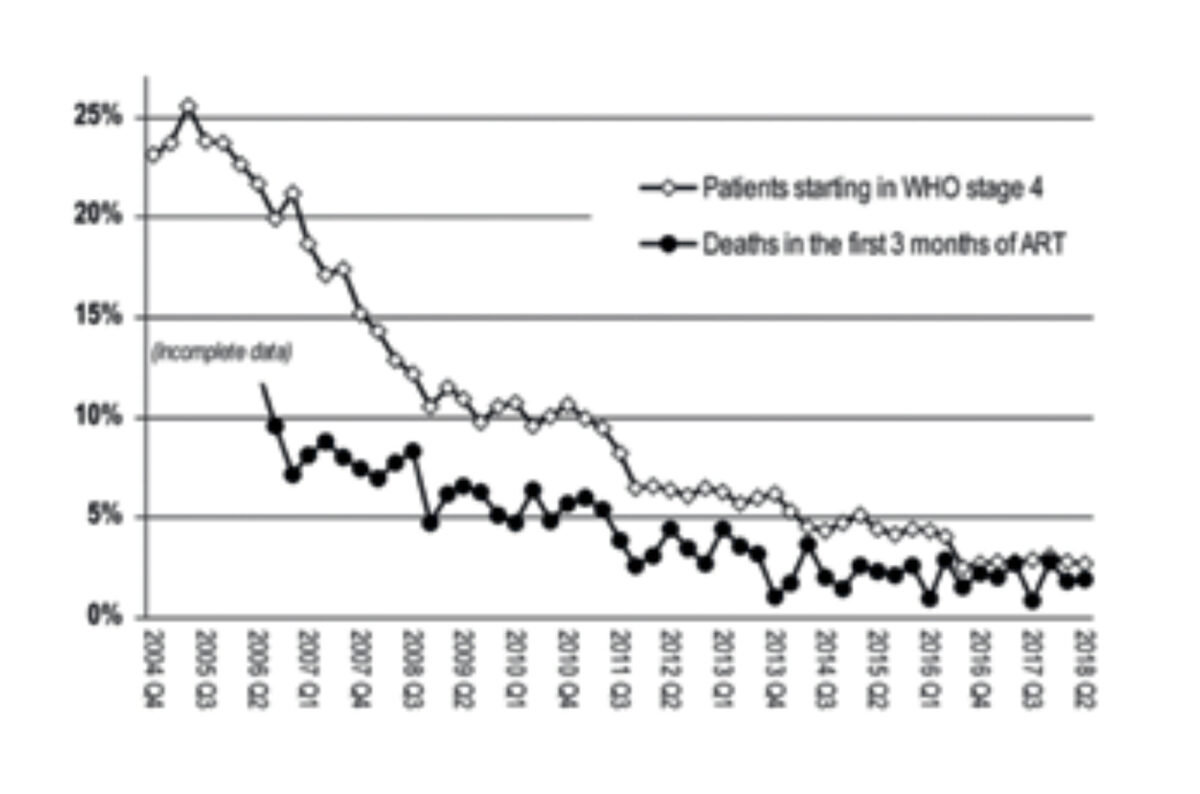

In the early years of the HIV programme, many patients who started ART had a low CD4 count and/or advanced clinical HIV disease (WHO clinical stage 3 or 4). The risk of death in the first year of ART was substantial. As the threshold for eligibility to ART was lowered over the years (by increasing the CD4 cell count level), fewer people initiated ART with an AIDS diagnosis and the 3-month mortality dropped steadily (Figure 2). Despite these positive trends, a remarkably large number of patients still present with advanced HIV disease, either due to late HIV diagnosis, defaulting from ART, or long-term ART failure. These patients are at high risk of dying, mainly from tuberculosis, cryptococcosis and severe bacterial diseases. This phenomenon is observed not just in Malawi but in the whole of sub-Saharan Africa. [10]

Evidence-based interventions for advanced hiv disease

The REALITY randomized clinical trial (RCT) conducted in Malawi, Uganda and Zimbabwe enrolled patients with CD4 lower than 100 cells/µL. It tested the benefit of enhanced anti-microbial prophylaxis (fluconazole, albendazole, ciprofloxacin and isoniazid), nutritional supplementation (with peanut butter based therapeutic food) and ART intensification (with raltegravir). The results showed that only anti-microbial prophylaxis reduces mortality, but it was not clear which of the antimicrobials contributed most to the result. [11] Two RCTs in Malawi, South Africa, Zambia, Zimbabwe and Uganda found that PLHIV admitted to a hospital benefit from screening for tuberculosis with urine lipoarabinomannan (LAM) testing in terms of reduced mortality, if it involves patients with clinical tuberculosis suspicion, severe anaemia and/or a low CD4 count. [12, 13] An RCT conducted in Tanzania and Zambia enrolled nearly 2,000 ART-naive adults with CD4 <200 cells/µL. The study showed that cryptococcal antigen screening in blood, followed by antifungal treatment if found positive, in combination with community-based support for ART adherence, improves survival. [14]

Following these study results, Malawi 2018 HIV guidelines have included lateral-flow cryptococcal antigen screening and urine LAM testing in all patients with advanced HIV disease, including all PLHIV admitted to medical wards of hospitals, whatever the reason for admission. In addition, implementation of isoniazid prophylaxis has started in high tuberculosis burden districts on top of cotrimoxazole prophylaxis, which has been part of the preventive package since 2004.

From a health systems perspective, the challenge of preventing advanced HIV disease is considerable with few evidence-based options. A promising new development is the ‘welcome back clinics’ to make it easier for those who have defaulted from ART to return to care. Likewise, efforts to better engage men in the health system are important, given that male gender is strongly associated with late HIV disease presentation. [15] Annual routine viral load monitoring, timely forwarding of viral load results to patients, and acting on these results by switching to next line ART, if indicated, can prevent long-term ART failure. However, this is expensive and poses logistical challenges.

The Malawi hiv programme is a model for the public health approach to antiretroviral therapy (art) in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Conclusion

Over the course of 15 years and under difficult circumstances, the Malawi Ministry of Health has built a high-quality, evidence-based HIV programme together with multiple stakeholder organizations. However, multiple challenges remain, for instance the continuing presentation of advanced HIV disease.

| PMTCT options in resource limited settings in 2011. [2] WHO Option A (for women who are not eligible for triple drug ART due to their own health): Antepartum zidovudine started from 14 weeks’ gestation; plus single-dose nevirapine at onset of labour, plus zidovudine/lamivudine during labour and delivery and continued for 7 days’ postpartum WHO Option B (for women who are not eligible for triple drug ART due to their own health): Triple drug ART started from 14 weeks’ gestation until 1 week after exposure to breastmilk has ended Malawi’s Option B+ (irrespective of whether women are eligible for triple drug ART due to their own health): Life-long, triple drug ART started from 14 weeks’ gestation |

References

- Jahn A, Harries AD, Schouten EJ, et al. Scaling-up antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Bull World Health Organ 2016; 94:772-776. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.2471/BLT.15.166074

- Schouten EJ, Jahn A, Midiani D, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV and the health-related Millennium Development Goals: time for a pub-lic health approach. Lancet. 2011; 16;378(9787):282-4.

- Bewley S, Welbourn A. Should we not pay at-tention to what women tell us when they vote with their feet? AIDS 2014; 28:1995.

- van Lettow M, Landes M, van Oosterhout JJ, et al. Prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a cross-sectional study in Malawi. Bull World Health Or-gan. 2018; 96(4):256-265. doi: 10.2471/BLT.17.203265.

- Tippett Barr BA, van Lettow M, van Oosterhout JJ, et al. National estimates and risk factors associ-ated with early mother-to-child transmission of HIV after implementation of option B+: a cross-sectional analysis. Lancet HIV 2018. pii: S2352-3018(18)30316-3. doi: 10.1016/S2352-3018(18)30316-3.

- Government of Malawi Ministry of Health. Integrated HIV program report: April-June 2018. Lilongwe: Malawi Ministry of Health, 2016.

- Jahn A, Floyd S, Crampin AC, et al. Population-level effect of HIV on adult mortality and early evidence of reversal after introduction of antiretroviral therapy in Malawi. Lancet. 2008;371(9624):1603-11. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60693-5.

- van Oosterhout JJ, Mallewa J, Kaunda S, et al. Stavu-dine Toxicity in Adult Longer-Term ART Patients in Blantyre, Malawi. PLoS One 2012; 7(7):e42029.

- Carr DF, Chaponda M, Jorgensen AL, et al. Association of Human Leukocyte Antigen Alleles and Nevirap-ine Hypersensitivity in a Malawian HIV-Infected Population. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56(9):1330-9

- Guidelines for managing advanced HIV disease and rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy, July 2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2017.

- Hakim J, Musiime V, Szubert AJ, et al. Enhanced Prophylaxis plus Antiretroviral Therapy for Advanced HIV Infection in Africa. N Engl J Med. 2017; 377(3):233-245. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1615822

- Peter JG, Zijenah LS, Chanda D, et al. Effect on mortal-ity of point-of-care, urine-based lipoarabinomannan testing to guide tuberculosis treatment initiation in HIV-positive hospital inpatients: a pragmatic, parallel-group, multicountry, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2016; 387(10024):1187-97. . doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01092-2.

- Gupta-Wright A, Corbett EL, van Oosterhout JJ, et al. Rapid urine-based screening for tuberculosis in HIV-positive patients admitted to hospital in Africa (STAMP): a pragmatic, multicentre, parallel-group, double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2018; 392 (10144): 292-301. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31267-4.

- Mfinanga S, Chanda D, Kivuyo SL, et al. Cryptococ-cal meningitis screening and community-based early adherence support in people with advanced HIV infection starting antiretroviral therapy in Tanzania and Zambia: an open-label, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015; 385(9983):2173-82. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60164-7.

- Dovel K, Yeatman S, Watkins S, Poulin M. Men’s heightened risk of AIDS-related death: the legacy of gendered HIV testing and treatment strate-gies. AIDS. 2015; 29: 1123-5. doi: 10.1097/QAD