Main content

Vaccines are commodities for which ordinary market mechanisms do not apply. Their development including clinical testing, the production process, their shelf lives, and their often very limited supplier base, in combination with unpredictable disease outbreaks and epidemics, regularly lead to vaccine shortages. It is good to realise that vaccines are a public good and access needs to be equitable. From a public health point of view, national health authorities and international development partners need to ensure steady supplies and the efficient and fair distribution of scarce vaccines to places where they are needed most. With new vaccines entering the market and many parts of the world in civil or military turmoil, where outbreaks and epidemics thrive, reliable mechanisms for vaccine supply chain management are of paramount importance. Vaccination is a main pillar in emergency responses and disease outbreak management while the vaccine market has gradually become more complex. Ample supply is not a given anymore, e.g. only one manufacturer remains for the yellow fever vaccine. Ordinary lead times may be up to two years, shelf lives differ between different types of vaccines, and supply chain requirements have become more differentiated. Modern vaccines are very complicated in terms of production and quality control. As always, politics reign in this field as well, necessitating a fair public health approach which strives for equity and efficiency. This article describes the role of The International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision (ICG) in ensuring that scarce vaccines are available where they are needed as part of disease control.

Background

Triggered by an outbreak of cerebrospinal meningococcal meningitis in in 1996 in West-Africa, the ICG was established as the International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision for Epidemic Meningococcal Disease. The outbreak affected primarily Nigeria and Burkina Faso, with a total of 152,813 confirmed cases and 15,783 registered deaths. The actual incidence was probably considerably higher.

Since its establishment, the ICG has undergone several changes. In 2001 Yellow Fever (YF) vaccine was added to its mandate, followed by Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV) in 2013. The ICG has three guiding principles: [1]

- Equity: distribution of vaccines based on public health priorities;

- Rapid and timely access: delivery of vaccines within a defined timeframe to control outbreaks;

- Independence: decisions made independently of political or economic influences, with the sole goal of improving public health.

Initially the ICG used a revolving fund to pre-finance the purchase of vaccines, vaccine-related supplies, and antibiotics. Countries were expected to reimburse the cost of vaccines drawn from the ICG stockpiles that were kept by manufacturers in their warehouses to enable replenishment. In 2002, the Gavi Alliance (see the article on GAVI elsewhere in this edition) started providing financial support, initially for the procurement of YF vaccine, later also of Meningitis vaccines (2008) and OCV (2013). At Gavi’s request, the ICG stopped the reimbursement requirement for Gavi support-eligible countries in 2015. A year later, Gavi decided that investments in emergency vaccine stockpiles would no longer be time-bound and that non-Gavi-supported countries were also eligible to access vaccines from the stockpiles, in the understanding that they would ensure replenishment, with Gavi covering the financial risk in case they failed to do so.

The supply division of UNICEF plays a key role in this process, as it procures all the vaccines for the ICG stockpiles. [2] The revolving funds are now dormant, leaving the Gavi Alliance as the sole funding source for these stockpiles. Gavi also provides funding to support the operational costs of emergency immunization campaigns in Gavi-eligible countries.

The ICG Executive sub-Group is constituted by its 4 founding members: WHO, UNICEF-Headquarters, Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), and the International Federation of Red Cross (IFRC). Other stakeholders, such as UNICEF’s Supply Division (Copenhagen), Agence de Médecine Préventive (AMP), Centre for Disease Control, manufacturers, international NGOs, technical agencies, financial partners and country representatives (two from countries in the African meningitis belt, plus a third country) support various activities of the ICG mechanism, e.g. decision-making, forecasting of vaccine requirements, procurement, and deployment. The ICG Executive sub-Group reviews requests not only from countries but also from international organisations that act swiftly in the event of disease outbreaks such as MSF. It can do so within 48 hours after receipt by its secretariat of a formal request.

Standard operating procedures for emergency stockpiles of meningitis and YF vaccine (but not for OCV) are in place for vaccine applications, release, financing, replenishment, monitoring, and reporting. In 2015, discussions started about an ICG mechanism for a future Ebola vaccine. [3] An ICG Ebola expert group is not in place though.

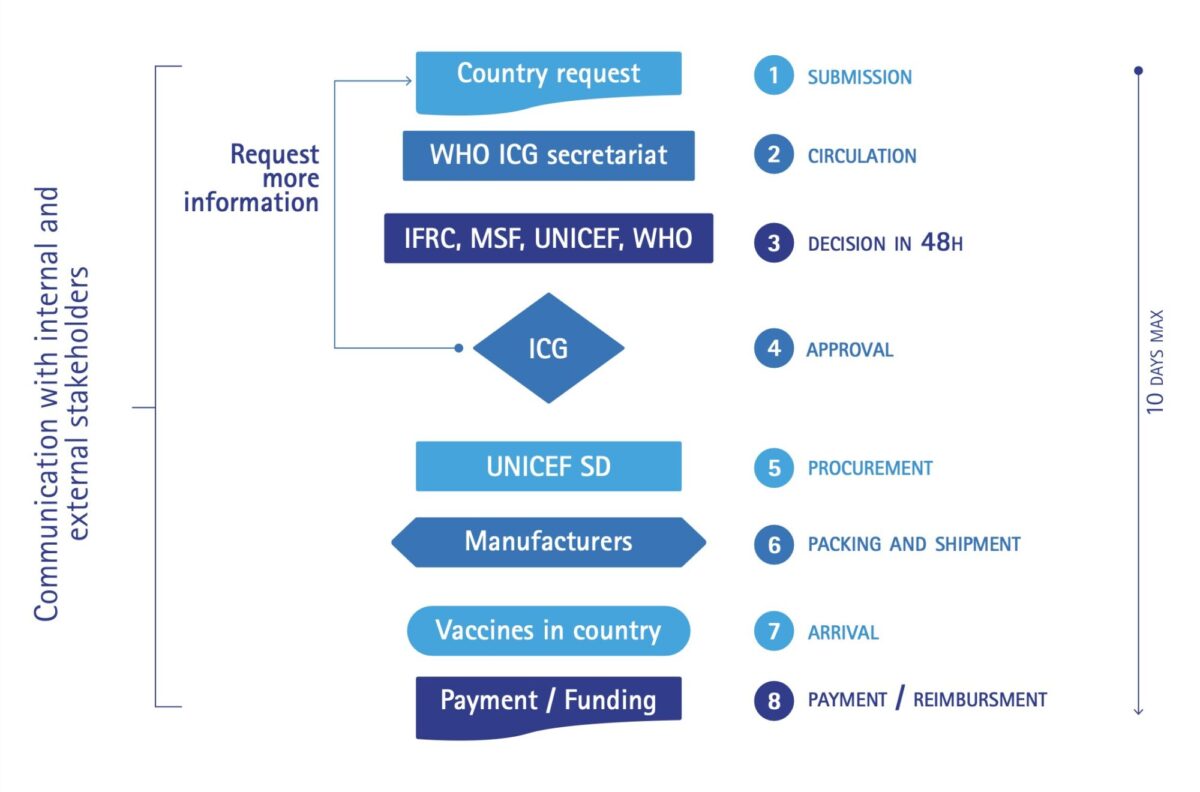

The full ICG meets physically twice a year as well as through remote digital conferencing in the event of an emergency request. The ICG Secretariat based at WHO-HQ plays a central and coordinating role in the entire ICG mechanism. It also does price negotiations through its constituency and network, and evaluates interventions and standard protocols for managing vaccine-preventable diseases. Its informality and flexibility is a key strength. Vaccines are allocated based on technical and public health criteria without political or financial considerations. The ICG mechanism is depicted in Figure 1. It aims at delivering vaccines within a time span of a maximum of 10 days after receipt of the request.

Recent major outbreaks – yellow fever in DR Congo and Angola, cholera in Yemen and the Horn of Africa – have confirmed the need for effective management and distribution of vaccines of which the supply can be unreliable. In 2017 for example, the ICG had to prevent Angola from procuring large quantities of YF-vaccine that would have left the border area in DRC exposed to further spread of the epidemic. The criteria used during decision-making differ among the three stockpiles because each outbreak has its own peculiarities. These criteria are publicly available. [4,5,6] The balance between responding to single outbreaks and considering the global epidemic context is and remains delicate. When working in epidemic or outbreak settings, public health experts should be aware of ICG’s existence and its modus operandi so they can act and advise in an appropriate manner.

The global disease control context

The occurrence of and response to disease outbreaks need to be seen in the context of global disease control strategies. In many cases outbreaks are the consequence of insufficient coverage of routine immunisation systems and failure to compensate for that with effective special immunization activities, including campaigns. While ministries of health with the support of various partners usually implement control programmes for meningitis, YF and cholera through routine preventive and reactive immunisation, it is the ICG that coordinates the management of the three vaccine stockpiles, especially in emergency outbreak situations.

1. Cholera

In 2013, WHO established the Global Oral Cholera Vaccine (OCV) stockpile, and the Global Task Force on Cholera Control (GTFCC) launched a renewed strategy for cholera control in which OCV plays an important role. [7] Many countries are now integrating the use of OCV within their cholera control programs. As of May 2018, over 25 million doses had been administered in 19 countries – of which 41% in humanitarian situations, 38% for outbreaks, and 21 % for endemic areas.

2. Yellow fever

The Yellow Fever Initiative was launched in 2006 as a joint collaboration of WHO and UNICEF. In 2016, a new more specific and comprehensive strategic approach towards the Elimination of Yellow fever Epidemics (EYE) was developed. [8] It involves a mechanism that automatically replenishes the emergency stockpile to ensure that 6 million doses are available at all times. The ICG remains responsible for rapid and independent decision-making on the allocation of YF vaccines during emergencies.

3. Meningitis

There is no single strategy that combines prevention, routine immunisation, and emergency responses for meningitis. At present the supply of serogroup A meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenAfriVac) is adequate and affordable, which has helped substantially to reduce the number and severity of meningitis outbreaks in countries of the African meningitis belt. However, meningitis outbreaks are now dominated by other meningococcal serogroups, for which conjugate vaccine supplies are insufficient and expensive.

4. Ebola

The recent approval of an Ebola vaccine following outbreaks in West-Africa and the eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) shows that there is political will and funding to develop new vaccines in a much shorter time that ever before. An important milestone in 2015 were the trials in which more than 16,000 volunteers in Africa, Europe and the United States received the rVSV-ZEBOV vaccine. The vaccine was found to be safe and to offer protection against the Ebola virus. Following further testing during Ebola outbreaks in DRC/Equateur province (in May-July 2018) and DRC/North Kivu province (still ongoing) and consultations by the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunization (SAGE), the Ebola vaccine was formally approved and licensed by WHO in November 2019, just before this paper went to press. [9] It means that the vaccine can now widely be used, rather than under certain restrictions (‘expanded access’ or what is also known as ‘compassionate use’). Ringfencing vaccination in combination with early case detection and widespread vaccination of health staff working in outbreak situations will certainly boost demand. Considering the experience with bivalent polio vaccine, which was in short global supply for some time, undermining the smooth implementation of the global polio eradication strategy, it remains to be seen whether industry can meet the future demand for Ebola vaccine.

Conclusion

Since infectious agents can spread faster than ever after an outbreak, even from very remote areas, vaccine-preventable disease control is of global public health importance. Both management and financing of vaccine development and supply need to be secured through close coordination of all stakeholders: national authorities, international health organisations, international and national NGOs, and the vaccine manufacturing industry. The ICG, with its secretariat based in WHO headquarters, plays a key role in monitoring and guiding vaccine provision. Its mandate and capacity need to be safeguarded, free from any (geo)political interference. While comprehensive and adequate mechanisms are in place for the three vaccines discussed above that fall within ICG’s mandate, the recent approval of an Ebola vaccine shows that there is political will and funding to develop new vaccines in a much shorter time that ever before. It is opportune to now also safeguard the provision of Ebola vaccine. The ICG could fulfil that role.

Acknowledgement: This article is for a substantial part based on the report of an evaluation of the ICG in 2017 by a team from HERA-Belgium, of which the author was a member. The author acknowledges the contributions of fellow team members Dr. Josef Decosas, Leen Jille and Marieke Devillé.

References

- World Health Organization: Review of the International Coordinating Group on Vaccine Provision, 2006-2016. WHO Geneva, 2016

- www.https://www.unicef.org/supply/

- International Coordinating Group for Ebola Vaccine, Ist Meeting, 11 December 2015 – WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Switzerland

- Meningitis guidelines: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/154595/1/WHO_HSE_GAR_ERI_2010.4_Rev1_eng.pdf?ua=1

- Yellow fever guidelines: http://www.who.int/csr/disease/icg/ICG-request-form-EN.pdf?ua=1

- OCV guidelines: http://www.who.int/cholera/vaccines/Briefing_OCV_stockpile.pdf?ua=1

- https://www.who.int/cholera/task_force/en/

- https://www.who.int/csr/disease/yellowfev/eye-strategy-and-global-agendas/en/

- Burki T. Ebola virus vaccine receives prequalification. Lancet 2019; 394(10212):1893. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(19)32905-8/fulltext?dgcid=raven_jbs_etoc_email