Main content

Public-private partnerships (PPPs) in the context of global health attract a lot of interest and resources. Governments around the world, especially in Europe and the United States, have increasingly engaged with the private sector in developing and financing health infrastructure and technologies and in delivering health services through PPPs. While public support for development cooperation in the Netherlands has decreased quite substantially in the past decade, the interest in cooperation between public and private parties to tackle poverty and other global problems seems to have grown – or at least it has not faded. What is it that PPPs in health try to achieve? What characterises a sound PPP? What are the benefits and the critical conditions for success and what are the controversies? And is there any evidence that warrants the high expectations that are often placed upon such partnerships? How does one assess their performance in the first place? A special session organised by NVTG at the European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health in Basel, in September 2015, addressed these questions.

The evidence (of what works and what doesn’t) is rather anecdotal

Dimensions

PPPs are diverse in nature. We find them not only in health but also in urban development projects and the housing, water supply, and transport sectors. Many government led initiatives, new or old, emphasise the support they receive from commercial, sometimes multinational, firms or from international not-for-profit NGOs. Private associations and firms tend to strengthen their corporate social responsibility profile, for instance by improving the working conditions of their employees or by engaging in development initiatives related to their core business, in their own countries or abroad. Some of them engage in charity. At the global level, transnational initiatives such as the Global Fund for AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, and the Global Alliance for Vaccines Initiative are forms of public-private initiatives in which several agencies of the United Nations play a prominent role [1]. The Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs supports various international PPPs in health, agribusiness or other sectors [2]. In its relationship with development organisations, the Ministry prefers to present itself no longer as a donor, but as a partner, or at least as a promoter of strategic partnerships aimed at socio-economic development [3]. At the same time, it has not gone unnoticed that since 2012 we no longer have a Minister (or State Secretary) of Development Cooperation but a Minister of Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation. This demonstrates the present government’s intention to strengthen the link between trade and development, and between public policy and private commercial interests. Examples can be found in the area of food, nutrition and agribusiness (e.g. the Ghana School Feeding programme, with involvement of the World Food Programme and Unilever), market chain development (e.g. the Dutch Sustainable Trade Initiative, which is active in the cocoa, cotton, soya, timber, tea and tourism sectors), medical technology (e.g. Philips Medical Systems supplying radiology and imaging equipment to district-level hospitals in Africa, supported through ORET, a facility funded by the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs that promotes Development-Related Export Transactions), information communication technology (e.g. mobile phone technology in Africa), microfinance and microcredit (Queen Maxima), and health insurance (see the article about PharmAccess elsewhere in this edition of MTb). Some of these PPPs have been evaluated and they all invest a lot in promotion and public relations.

Are PPPs a healthy option?

A recent systematic review with this exciting title, published in Social Science and Medicine, identified more than 1400 publications about PPPs from a wide range of disciplines over a 20-year period [5]. One of its sobering conclusions was that there is little conceptualisation and in-depth empirical investigation into how PPPs actually work. One of the many definitions of a PPP is the following: ‘An arrangement – formal or informal – between two or more entities, of which one public and one private party, that enables them to work cooperatively towards shared or compatible objectives, and in which there is some degree of shared authority and responsibility, joint investment of resources, shared risk taking and mutual benefit’. However, it is good to realise that sometimes the very purpose of PPPs is to break through the strict boundaries between government led strategies and free market forces. This can be tricky, especially when the PPP involves the delivery of public goods, such as health services, education or drinking water. Some of the key dimensions of PPPs, identified in the systematic review include: shared objectives, joint investments, bundling, sharing of risks, sharing of benefits, inter-organisation relationships, contractual governance, power and information sharing. The typical strength of a PPP that is often mentioned lies in the distinct roles of the private and public parties involved. Private companies bring in certain technical knowledge and skills and they are generally considered good at innovation, with a certain dose of entrepreneurship and managerial efficiency. Public parties are considered necessary for creating the right enabling environment, promoting social justice and ensuring public accountability. The latter implies that engaging in PPPs in countries that have a poor track record on governance may be tricky. It is further important to note that PPPs in the context of global health usually involve more than just one national government. For instance, in PPPs supported by the Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs and (co-) implemented in Africa by private firms, it would be an omission not to engage with the national governments of those countries where the PPP products and services are actually delivered.

Critical success factors

Based on surveys among practitioners who participated in cross-sector partnerships (not necessarily PPPs), the Partnerships Resource Centre of the Erasmus University in Rotterdam identified a set of critical success factors of partnerships [6]. These include: (1) clarity of roles and responsibilities and some ground rules for working together (2) a common understanding of mutual benefits (3) a clear vision of objectives (4) sound communication, shared planning and decision making and (5) leadership. One could argue that these also apply to international PPPs for health, and they are not to be taken for granted. Think only of corporate cultures in the private sector, which are often quite different from those in (semi-) government institutions. This means that smooth cooperation is not automatic. The Ghana School Feeding Programme, for example, which was set-up as a pilot in 2005, faced a lot of difficulties and has drawn strong criticism, partly because of an apparent gap between the aspirations and approach of its Dutch architects and the socio-cultural values held by local programme implementers and beneficiaries.

PPPs as an alternative for development cooperation?

Critiques, controversies

Several organisations and advocates have come out strongly against excessive faith in PPPs. Oxfam and the People’s Health Movement, for example, have criticised the World Bank’s privatisation policy and certain PPPs that attracted huge sums of taxpayer money. In a report that carries the ominous title ‘Why public-private partnerships don’t work’, David Hall, a scholar in the UK, explores the importance of public investment and examines private sector motives, capabilities, influence and performance [7]. Arguing that experience over the past 30 years has shown that privatisation is fundamentally flawed and trying to explain the resurgence of this phenomenon in the form of PPPs, he argues that PPPs ‘… are used to conceal public borrowing …’ and that they are ‘… fundamentally incompatible with protecting the environment and ensuring universal access to quality public services’. Basically the controversies centre around questions such as the following. Who benefits from PPPs? Who carries the risk? Are local stakeholders (read: beneficiaries) sufficiently represented in how these PPPs are designed and governed? How do they affect public sector capacity, and the people’s trust in the public sector? In short, do PPPs have a role to play in achieving sustainable development goals?

Evidence so far

The evidence that PPPs are actually instrumental in achieving better health or development in general has been diverse so far. The scrutiny by researchers comes from various disciplines, but it’s striking that accountancy, finance and public administration predominate. This is understandable, as financial value and risk transfer are at the heart of PPPs. But there appears to be insufficient attention from strategic management fields such as human resources, management information systems, procurement & supply chain management, and governance. WHO has recognised these as health system building blocks, i.e. essential sub-systems that make up a country’s health system [8]. It seems logical that the evaluation of a PPP that aims at introducing a new medical technology or a health insurance scheme would include an assessment of, for example, the local human resource implications, the information requirements, and the maintenance arrangements around the newly introduced technology/scheme. But that is usually not the case. Evaluations are usually not that comprehensive, as they tend to focus on just a few indicators, for instance the number of patients diagnosed or treated, or the part of the population that has enrolled in the new insurance scheme.

Emerging research themes

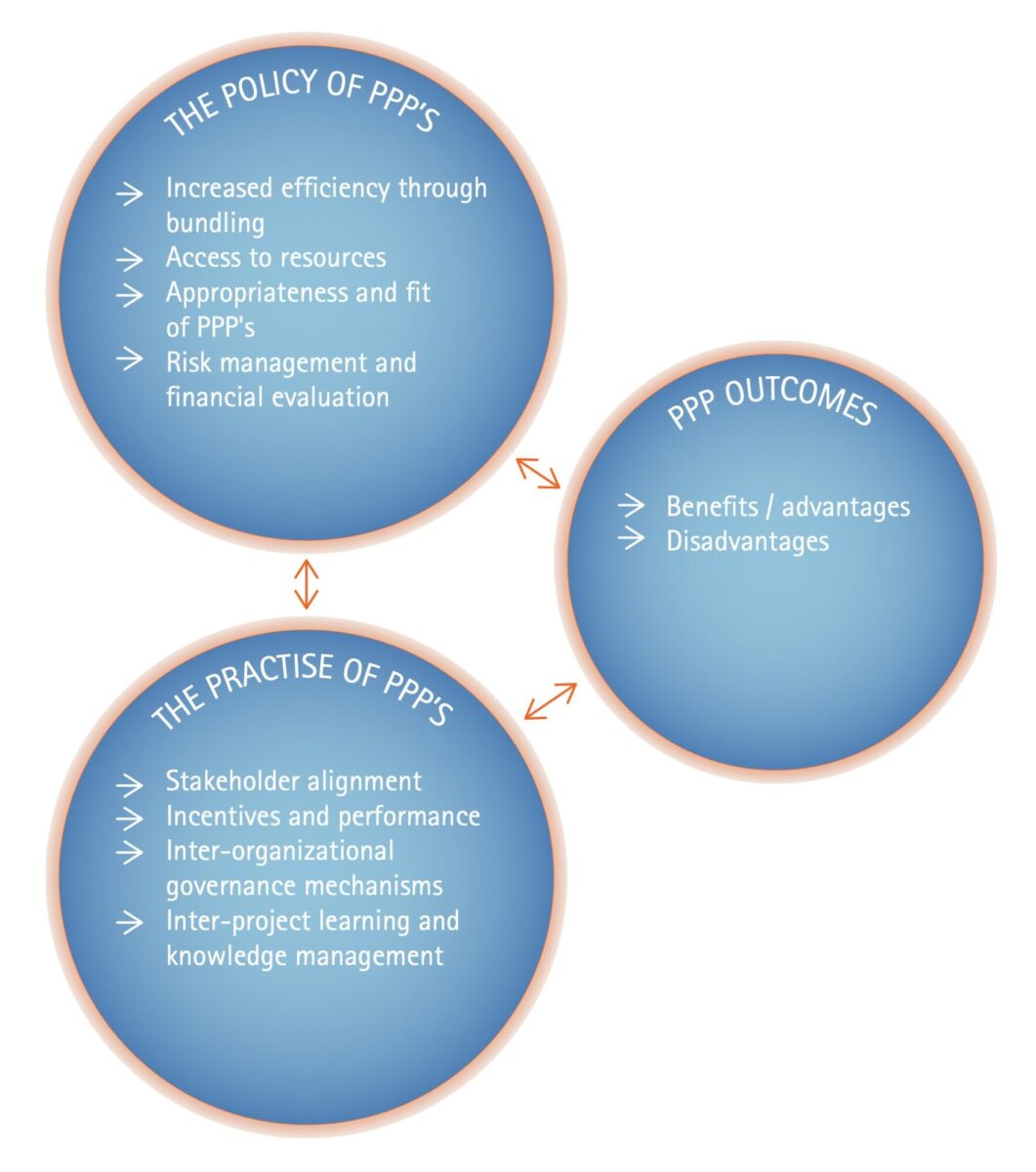

The systematic review by Roehrich and his colleagues [5] identifies three emerging research themes: PPP outcomes, PPP policies (with a focus on macro-level analysis) and the practice of PPPs (focusing on meso and micro levels). Bringing together these three key themes, the authors propose a multidimensional framework (see Figure 1) that integrates the manifold research streams and provides a basis for advancing both research and practice. This framework is useful, both for those wishing to do research on the functionality of particular PPPs and those who are already involved in policy making around PPPs or in the concrete management or implementation of programmes that have a PPP arrangement.

Adapted from Roehrig et al. (2014)

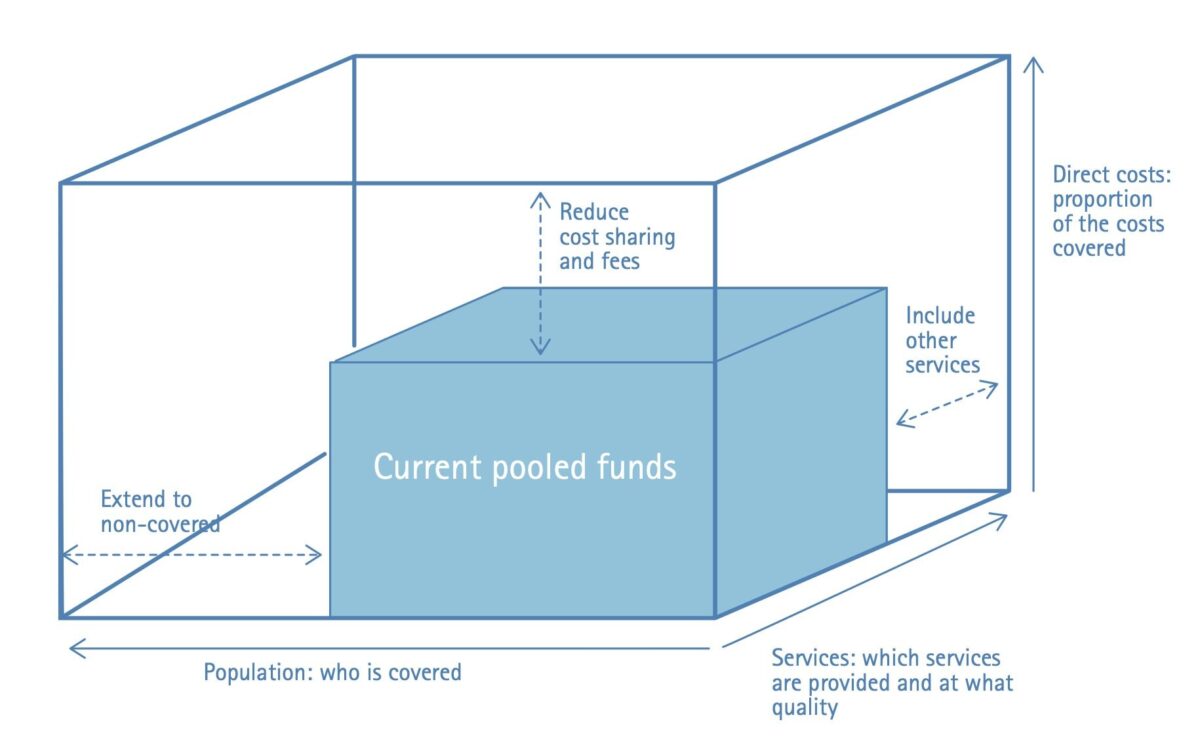

While PPPs can be very complex because of the variety of stakeholders involved, the multi-level ambitions, and the range of interests, which may or may not always be compatible, one could argue that the criteria by which the performance of a particular PPP would ultimately need to be evaluated are in fact quite simple and straightforward. In the context of global health, two ways of evaluating PPP performance could be considered. Firstly, the three dimensions of universal health coverage [9] would apply: (1) Which services or products are being delivered? (2) Who is covered? (3) At what cost? (see Figure 2.) The overall question is: What does the PPP contribute in respect of these three dimensions? In order to obtain a robust answer to this question through sound research, it is probably necessary to also include, or at least consider, the following question: What would have been the situation in the absence of the PPP?

Secondly, the OECD/DAC criteria for evaluating aid effectiveness could be applied: relevance, effectiveness, efficiency, impact and sustainability [10]. In addition, because of the complexity and the international dimension of PPPs, it would be appropriate to include some additional criteria such as transparency, accountability, legitimacy and environmental impact. Admittedly, this makes the PPP evaluation less simple and straightforward, as it calls for a mixed methods methodology.

Conclusion

PPPs in health are diverse, which makes it challenging to evaluate their performance. There is a large diversity in the extent to which they are successful – or claimed to be successful – even though the empirical evidence is scanty. Some of the critical success factors for PPPs have been reported on and appear to be universal. There is much less consensus about the precise criteria to be used, but the good news is that several sets of criteria already exist. It would be appropriate to invest more in research and apply these criteria when evaluating a particular PPP. We need to generate evidence and really learn from it, instead of simply assuming it works just because vested interests want it to work.

References

- Okma KGH, Kay A, Hockenberry S, Liu J, Watkins S (2015): The changing role of health-oriented international organizations and nongovernmental organizations. Int J Health Plann Mgmt. DOI: 10.1002/hpm.2298

- Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2011): Public-private partnerships – Ten ways to achieve the Millennium Development Goals. Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Sustainable Economic Development Department, The Hague

http://www.minbuza.nl/binaries/content/assets/minbuza/en/import/en/key_topics/development_cooperation/partners_in_development/public_private_partnerships/public-private-partnerships-ten-ways-to-achieve-the-mdgs - Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2015): Beleidskader: Samenspraak en tegenspraak – Strategische partnerschappen voor pleiten en beïnvloeden (2016-2010). Also available in English as Policy framework: Dialogue and dissent – Strategic partnerships for lobby and advocacy (2016-2020)

- Netherlands Ministry of Foreign Affairs (2014): In search of focus and effectiveness – Policy review of Dutch support for private sector development 2005-2012. IOB evaluation, no. 389

- Roehrich JK, Lewis MA, George G (2014): Are public-private partnerships a healthy option? A systematic literature review. Soc Sc & Med 113:110-119

- The Partnerships Resource Centre (2013): How to make cross-sector partnerships work? Critical success factors for partnering. Erasmus University, Rotterdam School of Management http://www.rsm.nl/fileadmin/Images_NEW/Faculty_Research/Partnership_Resource_Centre/brochure-How-to-make-cross-partnerships-work-2013.pdf

- David Hall (2015): Why public-private partnerships don’t work – The many advantages of the public alternative. Public Services International Research Unit (PSIRU), University of Greenwich, UK

- http://www.who.int/healthinfo/systems/monitoring/en/

- http://www.who.int/health_financing/universal_coverage_definition/en/

- http://www.oecd.org/dac/evaluation/daccriteriaforevaluatingdevelopmentassistance.htm

Further reading

- Byiers B and Rosengren A (2012): Common or conflicting interests? – Reflections on the Private Sector (for) Development Agenda. ECDPM, Discussion paper no.131. www.ecdpm.org/dp131

- Droppert H and Bennett S (2015): Corporate social responsibility in global health: an exploratory study of multinational pharmaceutical firms. Globalizaton and Health, 11:15

- Patouillard E, Goodman CA, Hanson KG, Mills AJ (2007): Can working with the private for-profit sector improve utilization of quality health services by the poor? A systematic review of the literature. Int J Equity in Health 6:17

- Pfisterer S, van Dijk MP, van Tulder R (2009): Effectiveness of the World Summit on Sustainable Development Partnership Programmes in East Africa and South East Asia – summary report. Final report for the Dutch Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Security and the Dutch Ministry of Foreign Affairs. ECSAD, The Hague