Main content

Original title: Nilen. By Terje Tvedt. H. Ascheboug & Co. (W. Nygaard), Oslo, 2021

Dutch edition: De Nijl. Biografie van een rivier. Translation Maud Jenje / Uitgeverij Wereldbibiotheek, 2022, 544 pages

English edition: The Nile. History’s greatest river. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 2021, 400 pages

The Greek poet Hesiodus, who lived between 700 and 600 BC, gave the river its name, Nilos (Νείλος), because the numerical value of the Greek letters was 365 – symbolizing “everything” as a description of the impact of the giant river not only on geography but also on imagination.

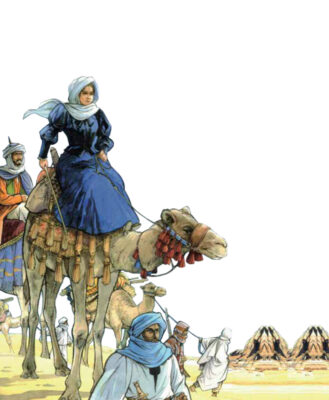

The Nile is the world’s longest river (6400 km) as measured from the origin of the White Nile, which originates in Uganda, to the delta at the Mediterranean Sea. The main reservoir is Lake Victoria, to which important tributaries contribute water originating in Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, Burundi and Congo. The Blue Nile begins in Lake Tana in the Ethiopian highlands, 2500 km from Khartoum, Sudan, where it joins the White Nile to continue as the Nile (Figure 1). Other important tributaries that receive water from Ethiopia are the Atbara River and the Sebat River. The Blue Nile contributes 80% of all water that eventually reaches Egypt; the water flow is highly seasonal as 90% of all the water flows through the river during 3 months in autumn, which illustrates the need for regulation of flow and reservoirs of water. The Nile has shaped the geographical history and lives of people who live in countries through which the river flows. While its early significance during the pharaonic times was thought to be ‘divine” and a source of life, later Egypt became the granary of the Roman Empire. The river kept its central position in the development and political history of all countries in the region up to the colonial times and after independence. Control of the flow of water has become the subject of political and (threatened) military conflict, as is still the case today. Terje Tvedt has extensively researched the Nile from all angles (historical, geographical, political, economic), and travelled widely to see and experience all major sections of the river in all the countries involved. He starts his travels in Egypt, and from there he travels upstream.

One geographical issue that was only solved in the late 1890s was the origin of the (White) Nile, an enigma that was already mentioned by early writers and historians such as Herodotus. Explorers such as David Livingstone, Henry Stanley and Richard Burton all failed to be the first to see where the White Nile begins its epic journey to flow through Uganda, South Sudan, and Sudan, where it joins with the Blue Nile to continue as the Nile to Egypt and the Mediterranean Sea (Figure 2). It was John Hanning Speke who discovered in 1862 that the White Nile originates at what is now called Jinja in Uganda, where the only outlet of Lake Victoria is located. This is called the Victoria Nile (Figure 3). Stanley reported in 1870 that all other connections of Lake Victoria with rivers are inlets that contribute water to the lake. In 1864, Samuel and Florence Baker discovered that the Victoria Nile described by Speke flows into Lake Albert to continue as the Albert Nile in north Uganda, which upon entering South Sudan changes its name to the White Nile (Figure 1).

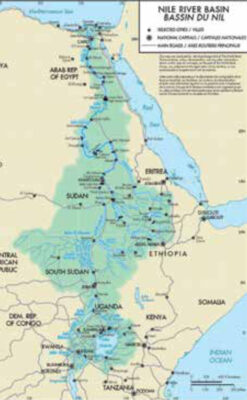

These were colonial times and, while the expeditions were supported by the Royal Geographical Society, the discoveries were important for the British Empire to establish control of the Nile for geopolitical purposes. Often explorers looked upon the indigenous peoples with disdain and ignored their interests. Nile water was essential for growing cotton in Egypt, which became part of the British empire in 1882. Hydro-politics was born. Nilometers were built at various places to monitor the water level (Figure 4). Control of the water flow from upstream was essential for agriculture. Dams were built to regulate the flow of water in the region and, later on, to provide hydroelectric power. After other European powers recognized that the course of the Nile was under British influence, Egypt and London signed the Nile Treaty in 1929, in which the use of water from the Nile was regulated to ensure that Egypt would have the right of vetoing all projects in the British colonies in the region that could decrease the flow of water to the country. As more countries became independent, the validity of this treaty was questioned, and the issue was renegotiated several times. The newly independent countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda, Rwanda, Burundi, and Congo all would have their say in managing the flow of water in the Nile.

Tvedt describes the history of all the countries subsequently and begins in Egypt. The developments in the past two to three centuries include the building of the first dam by Mohamed Ali, the Mameluke ruler of Egypt, in the 18th century to ensure water flow in his country. British colonial rule in the region was unsuccessfully challenged by Napoleon. Later, the huge Aswan dam was completed when Egypt became independent under Gamal Abdel Nasser.

Tvedt continues to describe important milestones in the history of all the countries involved, during colonial rule or after independence, such as Sudan (the rise and fall of the Mahdi), South Sudan (the unfinished Jonglei canal that would channel the flow of water to prevent evaporation in the Sudd swamp), Uganda (dictatorship of Idi Amin, with floating bodies of killed adversaries feeding the crocodiles), Rwanda (the genocide) and Ethiopia (the fall of Emperor Haile Selassie and his replacement by communist rule, and the recent building of the controversial Grand Ethiopian Renaissance dam in the Blue Nile).

This book is well worth reading for all those interested in the region. While it is well referenced and authoritative, it is rather lengthy as the author elaborates extensively on virtually all topics, which makes it difficult for the reader to remain focused on the main issues. A more concise account would have improved readability. It is also surprising that, despite the extensive geographical and historical descriptions, there are no maps and no detailed index. While the importance of the Nile for people’s health in terms of water and food is clearly presented, other health related issues are hardly addressed at all, such as the widespread risk of malaria, Dengue and other vector-borne diseases such as: bilharzia (hyperendemic in irrigation schemes e.g. in Sudan), animal and Human African Trypanosomiasis (HAT) (as evidenced by the presence of tsetse flies at Murchison’s falls [Figure 5,6]), and onchocerciasis (Sudan – the former Abu Hamed focus). In addition, crocodiles and hippopotamus attacks are a common threat.

The book ends with an anecdote on changing times; in 2019 (90 years after London, Egypt and Sudan discussed the flow of the Blue Nile, at the height of the British empire), President Trump invited the leaders of the former British colonies to the White House to discuss the controversial Renaissance dam in Ethiopia. Trump suggested that he would be happy to perform the opening of the dam. A better example of the changing political situation would be difficult to find.

The remarkable story of Alexandrine Tinne – the unlikely explorer

Alexandrine (Alexine) Tinne was born in 1835 in The Hague, the Netherlands. Her family was very wealthy and well connected in circles that included the Royal Family. This was the Victorian age and, unlike what was expected of her, she refused to be married as this would have prevented her from doing what she liked most: travel!

After having explored Europe, she and her mother Henriette travelled through the Middle East, later joined by her aunt Addy. She developed a passion for photography, exploring the influence of light and shadow. Their adventures were captured in letters that Henriette wrote on a regular basis to her increasingly worried family, relatives and friends, including King Willem I.

She travelled in grandeur; up to 30-40 boxes accompanied her party, including a desk and her iron-bed. Their travels on the Nile from Cairo to Khartoum were fraught with difficulties, including negotiating the Nile cataracts and sandstorms; part of the journey had to be completed by camel.

Nevertheless, the three ladies were always well-dressed and made a lasting impression on everybody they met, and their adventures were covered extensively in international newspapers.

Thereafter, Alexine became obsessed with finding the origin of the White Nile, similar to professional explorers such as Speke and Grant. They left Khartoum by boat and made it to the Sudd in South Sudan. She was shocked to see the horror of the slave trade in what is now South Sudan. Her encounter with slave traders filled her with disgust, and she was held by the slave driver headman for some time, who refused to let her leave because of her critical attitude.

Eventually they returned to Khartoum and decided to explore the origins of the Bahr el Ghazal (river of the gazelles) as a potential source of the White Nile. Aunt Addy stayed in Khartoum, and Baron Theodor von Heuglin and Hermann Steudner joined them as scientists. Then fate turned against her and her party. Her mother Henriette died of fever, as did von Heuglin. Alexine was also ill for weeks and increasingly weak, probably caused by cerebral malaria. She was saved by a rescue expedition sent by her aunt Addy from Khartoum. While preparing to travel back to Cairo, aunt Addy suddenly passed away. She met with her brother John in Cairo and passed to him the dead bodies of her mother, her aunt and 2 female servants. She refused to go back to Europe, and developed an interest in the mysterious Tuareg tribe. She learned their language before setting off to find them. During one of their encounters, she tried to interfere in a local quarrel and was killed. Her body was never found. She was 33 years old.

David Livingstone, who himself searched for the source of the Nile held her in high esteem, mentioning that despite the tragic events in her family, she persevered in her efforts to reach her goals, even against the odds.