Main content

Shortly after the European introduction in the 17th century of the expensive ‘fever tree bark’ to treat ‘intermittent fever’, accounts of fake Peruvian cinchona bark without any fever-reducing activity were reported. Falsification of medicines has been haunting malaria patients ever since. The reliability of health systems, control programmes, and public health interventions stand or fall by the quality of medicines. For malaria, antimalarials with no or only a little active ingredient have not only contributed to the rapid emergence of drug resistance against traditional compounds but also to a countless number of avoidable deaths due to untreated infections. In this brief overview, I will discuss the impact of falsified and substandard medicines in the field of malaria and some of the current challenges and prospects for tackling this globalized health problem.

A game of definitions

Awareness of the general problem of poor quality medicines has certainly increased over the past years, culminating in the adoption of a so-called Member State Mechanism by the World Health Assembly in 2012 to unite international action to tackle this public health threat. Sadly, very little real action has been taken since then, mainly because there is little consensus on the definitions among stakeholders due to the differences between public health perspectives and trade perspectives. Pharmaceutical companies are mainly concerned about intellectual property protection and pricing of their products, whereas (non-)governmental organizations focus on public health implications and the universal right to health. The terminology is therefore still confused. In general, ‘poor quality’ medicines can be lumped into two broad categories, falsified and substandard medicines, which were discussed previously in the article by Raffaella Ravinetto (see the box on page 11). Obviously these two categories are often difficult to distinguish because they are generally based on the motive of the manufacturer, which is not only difficult to prove but is often also irrelevant from a patient perspective. The distinction between falsified and substandard medicines is nevertheless regarded as important, because they represent deficiencies in different systems that might require different solutions, which will be covered more extensively later.

Double standards

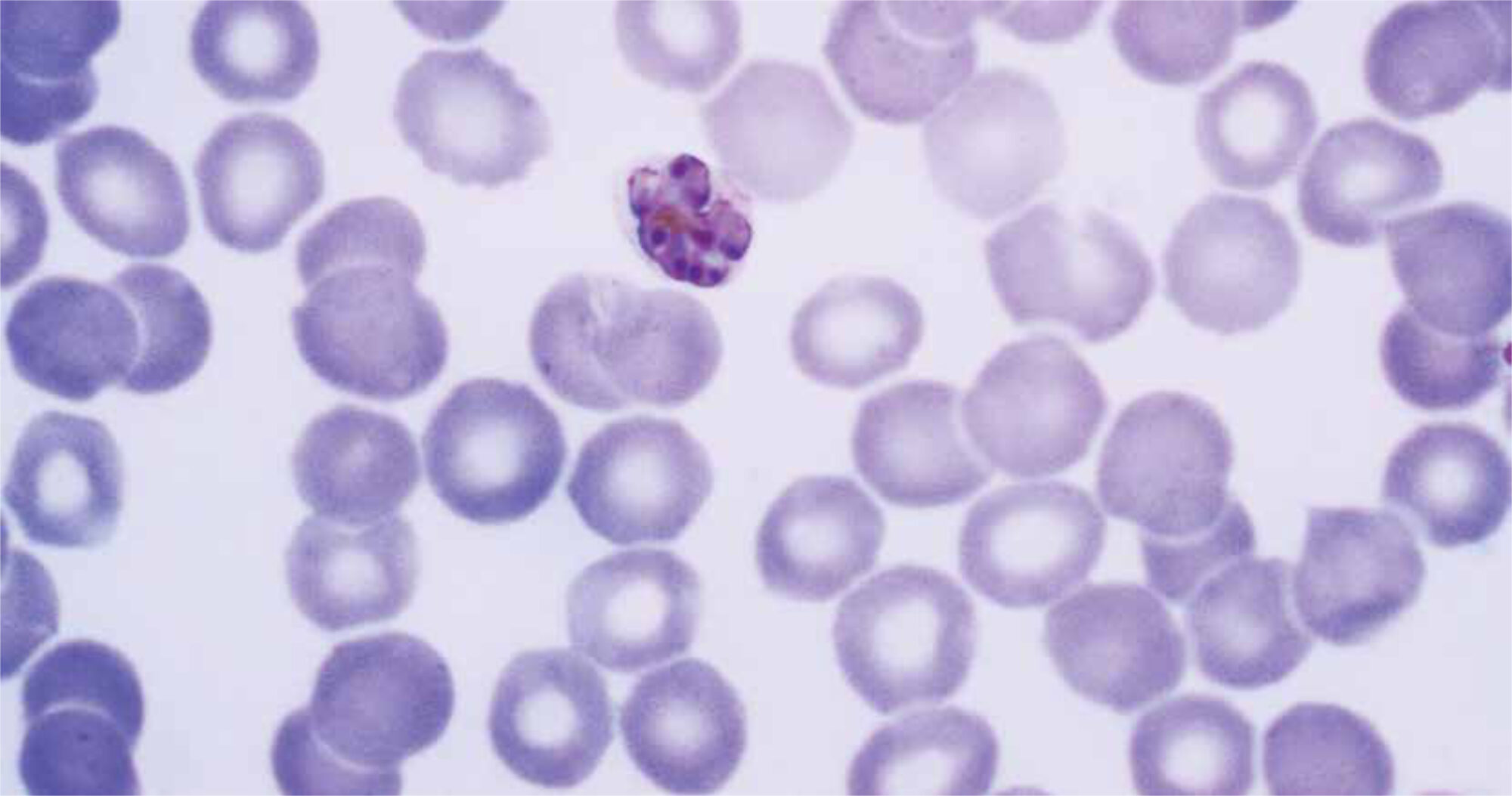

In regions where malaria is endemic, antimalarial medicines are widely available over-the-counter and often self-prescribed, with a lot of presumptive treatment of undiagnosed fevers. It is estimated that 300 to 500 million courses of antimalarial treatment are used every year worldwide. (1) The combination of poor consumer and healthworker knowledge about drugs and drug quality and the limited budget of poor patients makes antimalarial drugs a very attractive target for drug counterfeiters. Unfortunately, counterfeiting is not the only problem. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that only 7% of sub-Saharan African countries had a ‘moderately functioning’ National Regulatory Authority (NRA). The globalized pharmaceutical market, with the mainstay of generic production taking place in South Asia, has adapted to the differences in regulatory oversight which has led to different quality standards during (lawful) medicine production. (2) Both falsified and substandard antimalarials afflict therefore mainly the poorest and most vulnerable malaria patients. Since it is difficult to differentiate falsified from substandard drugs, the prevalence numbers below often include both categories and refer to the failing or passing of chemical and packaging analyses.

Epidemiology of a pandemic

Even though reports of poor-quality medicines have increased particularly in the field of malaria over the past two decades, the actual extent of the problem is difficult to assess due to methodological constraints in performing drug quality surveys. Concerns about the emergence and spread of resistance against many antimalarials have boosted investigations in the field of antimalarial drug quality, but these have not always applied proper methodologies, randomization and standardized chemical assays. (3) Nevertheless, all reported numbers indicate a growing pandemic that affects not only Southeast Asia, where the first reports on falsified artesunate originated, (4) but increasingly also sub-Saharan Africa. A meta-analysis of 28 antimalarial quality surveys published between 1999 and 2011 showed that, both in South Asia (7 countries) and sub-Saharan Africa (21 countries), 35% of the tested drug samples failed the chemical analysis, with either too little or no active ingredient. (5) A larger meta-analysis, including 529 surveys since 1946, indicated that almost all types of antimalarial drugs are affected, but the majority of surveys analysed samples of artesunate, chloroquine and sulphadoxine-pyrimethamine. (1) Oral artesunate was most commonly reported as being of poor quality, with 61.9% failing chemical or package analysis, compared to 30.1% overall. Falsified or substandard artemisinin derivatives-based combination therapies have hardly been encountered in Asia, with only 1 report on a Chinese seizure of drugs intended for export to Africa, in contrast to numerous reports from Africa (with 20.4% failure rate).

Nevertheless, there have also been recent positive signals indicating that the situation is improving in some countries. In Laos, no falsified artesunate was detected in a private sector survey in 2012, while in 2003 a similar survey still revealed 84% being falsified. (6) Also recent reports from both Cambodia and Tanzania indicated positive changes compared to previous reports, with no falsified artemisinin derivatives-based antimalarials and lower prevalence rates of substandards being found in the current surveys. (7,8)

Mapping the gap

There remain many blind spots on the antimalarial quality map. For approximately 60% of the 104 countries where malaria is endemic, we have no information at all on the prevalence of poor quality antimalarials. In particular, the situation in South and Central America remains unknown, with antimalarial quality data only available from 19% of the region’s malarious countries. Also, large parts of Central Africa have been neglected. There is only a single antimalarial quality survey reported from the Democratic Republic of Congo, Angola and Gabon, while these countries represent 40% of the estimated global malaria burden. So there are major concerns related to underreporting in almost all malarious regions. In addition, the origin of both falsified and substandard antimalarials is difficult to establish, due to a lack of regulatory oversight and forensic investigations in this area. One important tool has proven to be forensic pollen analysis, by which tiny traces of plant pollen that ended up in the drug samples during the manufacturing process can identify areas where these plants are common. This has consistently shown that the criminal production of falsified antimalarials mainly takes place in East Asia, even for the falsified drugs detected in Africa. (9)

Impact

Obviously, poor quality antimalarials containing little or no active ingredient lead directly to increased morbidity and mortality due to prolonged sickness and unresolved infections. Estimates indicate that, in 2013, ineffective poor quality antimalarials alone caused 122,350 deaths in children under the age of five in sub-Saharan Africa. (10) But falsified antimalarials are often not just inert but often contain other active and potentially harmful, ingredients. In the various antimalarial quality surveys, up to 20 different active ingredients have been found in falsified antimalarials, ranging from (a low amount of) other antimalarials to diazepam, chloramphenicol and even sildenafil, (1) which all may cause confusing adverse effects in unsuspicious patients. Patients may lose confidence in health-care providers and pharmacies and in the case of falsified medicines also in pharmaceutical brands. It leads to a financial loss for patients and their families but also for governments and complete health systems. However, the biggest threat resulting from poor quality antimalarials is their contribution to the emergence of drug resistance. The wide-spread availability of poor quality artemisinin-based drugs containing subtherapeutic amounts of active ingredient have arguably contributed to the tragic emergence of artemisinin-resistance in P. falciparum on the Thailand-Cambodia border. (11) For combination therapies, the risk of engendering drug resistance is dual: both the subtherapeutic active ingredient as well as the ‘unprotected’ co-ingredient increase the risk of resistance. Poor quality artemisinin derivatives-based combination therapies have been found all over the African continent. (1) These combination therapies are among the most crucial tools to control malaria in Africa. Losing them to drug resistance would be a public health catastrophe.

Control measures and challenges

There is no simple and fast solution to ensure good quality of all available antimalarials. Many proposed control measures focus on the detection of poor quality antimalarials, e.g. by standardized analytical methods, and on promoting prosecution of illicit counterfeiters. However, many of these approaches focus solely on falsified medicines and intellectual property protection. Substandard production by genuine manufacturers remains poorly addressed, partly because there is no consensus on its definition. Public health should nevertheless always be the prime consideration in combatting poor quality medicines. (12) Around 30% of countries have a non-functional or even non-existing NRA. Financial and technical support of regional and national regulatory authorities and the development of regional analytical laboratories in malarious regions are therefore absolutely pivotal to enable any interventions, surveys and routine inspections. This would not only allow more reliable screening for falsified medicines but also prevention of substandard production in lawful manufacturing facilities by increased enforcement of quality standards on manufactures and distributors. The investment and efforts in access campaigns to make essential antimalarials available can only be effective if their quality is ensured. Without prioritizing access to good quality antimalarials, current efforts to control malaria in Africa and Southeast Asia may be futile.

References

- Tabernero P, Fernández FM, Green M, Guerin PJ, Newton PN. Mind the gaps the epidemiology of poor-quality anti-malarials in the malarious world – analysis of the WorldWide Antimalarial Resistance Network database. Malar J 2014; 13:139.

- Caudron J-M, Ford N, Henkens M, Macé C, Kiddle-Monroe R, Pinel J. Substandard medicines in resource-poor settings: a problem that can no longer be ignored. Trop Med Int Health 2008; 13:1062-1072.

- Newton PN, Lee SJ, Goodman C, et al. Guidelines for field surveys of the quality of medicines: a proposal. PLoS Med 2009; 6:252.

- Newton P, Proux S, Green M, et al. Fake artesunate in southeast Asia. Lancet 2001; 357:1948-1950.

- Nayyar GM, Breman JG, Newton PN, Herrington J. Poor-quality antimalarial drugs in southeast Asia and sub-Saharan Africa. Lancet Infect Dis 2012; 12:488-496.

- Tabernero P, Mayxay M, Culzoni MJ, et al. A Repeat Random Survey of the Prevalence of Falsified and Substandard Antimalarials in the Lao PDR: A Change for the Better. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92:95-104.

- ACT Consortium Drug Quality Project Team, the IMPACT2 Study Team. Quality of Artemisinin-Containing Antimalarials in Tanzania’s Private Sector-Results from a Nationally Representative Outlet Survey. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92:75-86.

- Yeung S, Lawford HLS, Tabernero P, et al. Quality of Antimalarials at the Epicenter of Antimalarial Drug Resistance: Results from an Overt and Mystery Client Survey in Cambodia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92:39-50.

- Newton PN, Green MD, Mildenhall DC, et al. Poor quality vital anti-malarials in Africa – an urgent neglected public health priority. Malar J 2011; 10:352.

- Renschler JP, Walters KM, Newton PN, Laxminarayan R. Estimated under-five deaths associated with poor-quality antimalarials in sub-saharan Africa. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2015; 92:119-126.

- White NJ, Pongtavornpinyo W, Maude RJ, et al. Hyperparasitaemia and low dosing are an important source of anti-malarial drug resistance. Malar J 2009; 8:253.

- Newton PN, Amin AA, Bird C, et al. The Primacy of Public Health Considerations in Defining Poor Quality Medicines. PLoS Med 2011; 8:e1001139.