Main content

Lack of appropriate surgical care in many parts of the world has long been severely neglected. In the 1980s, Dr Mahler, at that time secretary general of the World Health Organization (WHO), stated that “surgery clearly has an important role to play in primary health care and in services supporting it”. Yet there is an undeniable discrepancy in surgical care and services between high-income countries (HICs) and low- and middle-income countries (LMICs), which hasn’t improved much over all those years. In 2015, still only 3.5% of the total estimated volume of surgery done worldwide was done for the poorest one third of the world population.[1] Meanwhile, hospitals in HICs have developed significantly over the past decades, from surgeons using a knife and stitches to hospitals packed with scanners, minimally invasive procedures, robotics, electric devices, distance control and technology driven highly specialised and sophisticated procedures, guided by well controlled quality systems. When one takes a single step in a rural or district hospital in any LMIC, the difference will immediately be felt.

Priorities from a global perspective

Can we alter inequalities in accessing quality surgical care, reflected in huge differences in outcome for any given surgical condition, despite forty years of discussions, meetings, assistance, cooperation, declarations, missions, training programmes, research, advocacy and so forth?

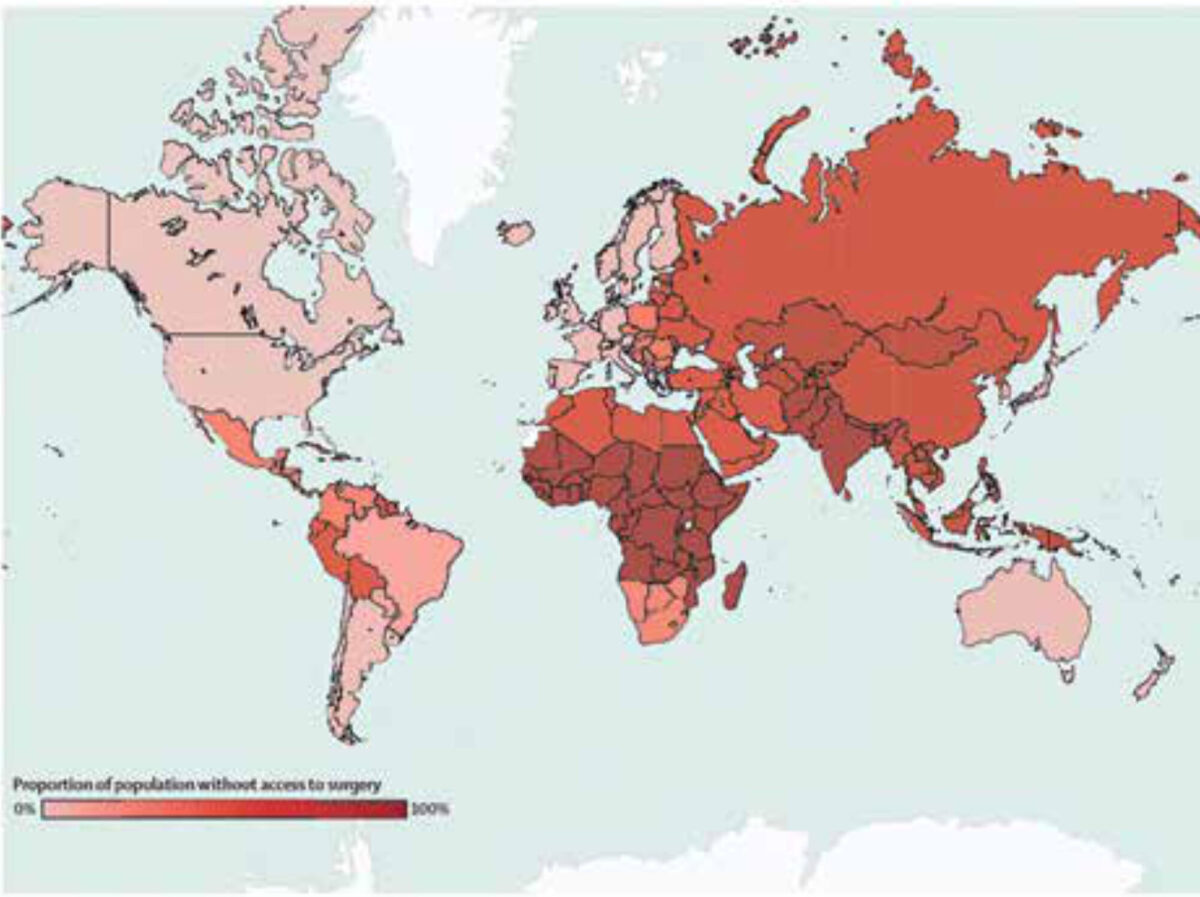

Conditions needing surgical care contribute significantly to the global burden of disease. Internationally up to 5 billion people cannot get timely and affordable proper surgical care when they are in need of it (Figure 1), and the need for surgical services is expected to rise until 2030. The first global reports on surgery were released and reported in 2013-2015: an estimated 16.9 million lives were lost (33% of all deaths worldwide) due to conditions needing surgical care, which was more than the total number of deaths from HIV, tuberculosis and malaria combined. The burden of untreated surgical conditions is highest in LMICS.[1] So to gain substation improvements in access to surgical care, we need a global strategy and joint effort. Investing in improvement of surgical care services is affordable and cost-effective.[2]

Yet from a health-economics perspective we are failing to realise this. The WHO calculated that of the US$ 8.3 trillion that was spent annually on health in 2018, more than 75% was spent in Europe and the Americas, while Southeast Asia and the Eastern Mediterranean regions each accounted for 2%, and the African region for 1%.[3]

In 2012, 88 LMICs* – together representing more than 70% of the world population – had still not reached targeted surgical volumes. If the historical scale-up rate of 5.1% of surgical services is continued, only 39 of those 88 (44%) will achieve the 2030 target, and GDP losses due to surgical conditions will largely overcome the total costs of its effect.[1]

Considering the need, it is worthwhile debating whether the gap in health care investment and expenditure is ethically justifiable.

Global surgery

Global surgery has been defined as “an area of study, research, practice, and advocacy that seeks to improve health outcomes and achieve health equity for all people who require surgical care, with a special emphasis on underserved populations and populations in crisis”.[4] It encompasses all kind of surgical interventions for common disorders such as hernias, acute abdomen disorders, and tumours. Moreover, surgery plays a vital role in cancer treatment. In most LMICs, prognosis of cancer is poor due to late presentation, scarcity of early diagnostic facilities, and lack of one or more of the multidisciplinary actors in oncology care, radiotherapy, chemotherapy and surgery.[5] Furthermore, many deformities and disabilities, either congenital or acquired, can still be found untreated in LMICS (e.g. cleft lip, clubfoot, cataract, contractures after burns and obstetric fistulas).

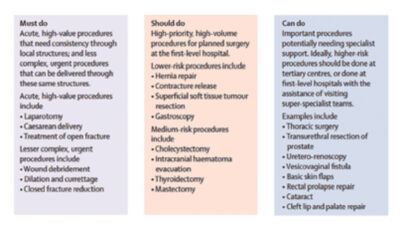

Basic surgical interventions can be divided into ‘must do’, ‘should do’, and ‘can do’ (Figure 2). The first category (must do) includes laparotomy, caesarean section and treatment of an open fracture. The second category (should do) includes among others hernia repair, cholecystectomy and evacuation of intracranial hematoma. The final category (can do) includes many surgical diagnoses such as cataract, prostatectomy, and vesicovaginal fistula, and is usually not urgent.

The big challenge is how to assure providing timely, high-quality must do and should do surgical interventions for any person worldwide, ideally within two hours of presentation. Despite many efforts, a considerable number of hospitals in LMICs are still not in the position to provide these treatment modalities for the most urgent surgical conditions, mainly due to a lack of well-trained staff and/or appropriate equipment.

Trauma and injury

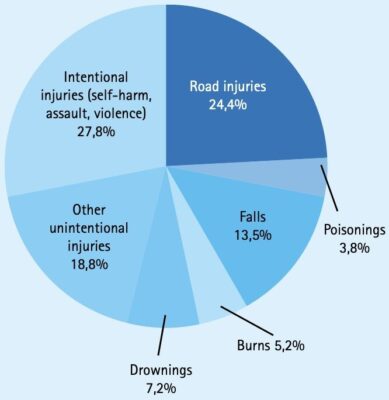

Injury is within the top 10 causes of death in LIMCs.[6] It is a major cause of temporary and permanent disability, leading to long-term absence from daily activities and loss of income. More than 90% of the injury deaths occur in LMICS. Road traffic injuries (RTIs) are responsible for the highest number of disability adjusted life years (DALYs)**, compared to all other diseases within the age group between 10-49 years, and this has been unchanged since the 1990s.[6] We are in a global trauma pandemic, and it is estimated that the incidence of injury and RTIs will increase due to increased mobility associated with economic development (Text box).

In the systematic approach to injury and trauma, surgery is an integral part of the trauma care system. Surgically trained professionals are responsible for the primary survey and resuscitation in the emergency room and the definitive clinical management (both operative and non-operative) of trauma patients as well as the follow-up of patients.

Next to general prevention measures and better prehospital care, surgeons and anaesthetists, together with other stakeholders (e.g. rehabilitation centres, physiotherapists etc.) in trauma care, are key actors in improving these statistics.

Considering injury is a major cause of mortality and morbidity, especially in LMICs, what can be done to address this problem?

In general, a systemic approach to trauma care, adapted to local context, is needed. Countries should include the development of a trauma system in their national surgical plans. For these trauma systems to be effective, training programmes should focus on making qualified surgical and anaesthesia staff available, 7 days a week and 24 hours a day, in all corners of the world. Although the Advanced Trauma Life Support (ATLS) system is the gold standard for reducing mortality in the first hours after the accident, it seems unlikely to be affordable for most LMICs, especially in rural areas. The more Adapted Primary Trauma Care (PTC) programme, provided free of charge, is a very good alternative, with the same surgical principles. The PTC is fully endorsed by the WHO and other partners.[7]

Also, it is recommended to train general duty doctors and clinical officers to perform basic trauma care (burns, fractures, soft tissue injuries), particularly in countries where specialist treatment is not readily available.[8] This means that trauma programmes should primarily be aimed at transferring skills and knowledge to health professionals, giving them the authority and trust to perform lifesaving interventions.

When it comes to preventing disability, most disabling fractures can be operated on in a systematic way, aiming to restore function and movement and so facilitating a quick return to daily life. Although in HICs these interventions for preventing disabilities are done by highly specialised (orthopaedic) surgeons, it has been shown that the use of standardised appropriate technology and methods can lead to similar results (and at lower costs) in low-resource settings.[9] Inclusion of relevant data on every operated patient in a global database, together with feedback and follow-up mechanisms, will ensure appropriate quality control as shown in the SIGN fracture care programme.[10,11]

Is there reason for optimism?

There is no ‘one fits all’ solution, and all too often ‘solutions’ were invented by motivated but biased surgeons from HICs. Equality between the parties involved was formally written down, but in practice not always felt by local stakeholders.

The (renewed) introduction of equality in international partnerships and global surgery research can be seen as a step in the right direction. With the Global Initiative for Emergency and Essential Surgical Care (GIEESC), the WHO has introduced an international platform where partners in global surgery can meet. As a result, related programmes are developed and organised at a local level and embedded in national plans – such as the national surgical obstetric and anaesthesia plan (NSOAP) – which are based on the understanding that local communities are best positioned to assess where the real needs are, including which areas to fund.

In my opinion, we need to fundamentally reshape our thinking about the nature of funding universal access to basic surgical care, in the same way that public health programmes are funded such as HIV, vaccinations, and mother and child care programmes.

It is not about donations or charity from rich to poor countries; it is our joint responsibility to provide all financing needed to ensure a certain level of basic surgical care around the world. The most straightforward way would be to allocate appropriate resources through the WHO to finance NSOAPS of LMICS. We must do so to save millions of lives. Hope can be derived not only from the WHA Resolution 68.15 Strengthening emergency and essential surgical and anaesthesia care is a component of universal health coverage which was unanimously adopted at the World Health Assembly in 2015 and can be seen as an universal commitment. Hope can also be derived from more recent declarations by world leaders at the latest World Health Summit on connecting global health programmes with climate change and the United Nations sustainable development goals.[12]

In conclusion, lack of essential surgical care should not be seen as a local problem but rather as a collaborative international responsibility to achieve global equality in surgical care by all means including training, sustainable technology, cooperation and funding. Only then will the goal of reducing surgical deaths have a chance of becoming reality.

| Text box: facts and figures of injury and trauma [13] 1.35 million people die each year as a result of Road Traffic Injuries. 93% of these fatalities occur in the LMICs, even though they have only 60% of the world’s vehicles. About 73% of all RTIs occur among young males. Proportions of injury categories in global mortality of all injuries, 2012.[14] |

Acknowledgement: I thank R. van Egmond for assisting with the manuscript.

*To our knowledge these are the most recent data on worldwide target surgical volumes.

**Disability adjusted life years (DALYs) is a measure of overall disease burden, expressed as the number of years lost due to ill-health, disability or early death.

References

- Meara JG, Leather AJ, Hagander L et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015 Aug 8;386(9993):569-624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X

- Chao TE, Sharma K, Mandigo M, et al. Cost-effectiveness of surgery and its policy implications for global health: a systematic review and analysis. Lancet Glob Health 2014 JUn;2(6):2334-45. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X (14) 70213-X

- World Health Organization. Global spending on health 2020: weathering the storm [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2020. 100 p. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/337859

- Dare AJ, Grimes CE, Gillies R, et al. Global surgery: defining an emerging global health field. Lancet. 2014 Dec 20;384(9961):2245-7. Doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60237-3

- Are C, McMasters KM, Guiliano A, et al. Global Forum of Cancer Surgeons: perspectives on barriers to surgical care for cancer patients and potential solutions. Ann Surg Oncol. 2019 Jun;26(6):1577-82. doi: 10.1245/510434-019-07301-2

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Global Health Estimates; 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/data/global-health-estimates

- GBD 2019 diseases and injuries collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet. 2020 Oct 17;396(10258):1204-22. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9

- Primary Trauma Care Foundation. Life Saving Action [Internet]. Oxford: Primary Trauma Care Foundation; 2019. Available from: https://www.primarytraumacare.org/

- Federspiel F, Mukhopadhyay S, Milsom PJ, et al. Global surgical, obstetric and anesthetic task shifting, a systematic literature review. Surgery. 2018 Sep;164(3):553-8. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2018.04.024

- Thomson Haonga B, Zirkle LG, The SIGN Nail: factors in a successful device for low-resource settings. J Orthop Trauma. 2015 Oct;29 Suppl 10:$37-9. doi: 10.1097/BOT.000○○○○○○○○○0411. Available from: https://www.signfracturecare.org/

- SIGN Fracture Care. Restoring limbs and livelihoods [Internet]. Richland: SIGN Fracture Care International. Available from: https://www.signfracturecare.org/

- World Health Summit. World Health Summit [Internet]. Berlin: World Health Summit. Available from: https://www.worldhealthsummit.org/

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2021. Road Traffic Injuries; 2020 Feb 7. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/road-traffic-injuries

- Mock CN, Nugent R, Kobusingye o, et al (editors). Injury prevention and environmental health: disease control priorities, volume 7. 3rd ed. Washington: The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank. 2017. 303 p.