Main content

Unaids 90-90-90 targets – mission impossible?

Antiretroviral therapy (ART) programs focusing on the prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission are the cornerstone of a remarkable success in scaling up ART globally. It is estimated that, since 2000, two million HIV infections in children have been averted thanks to ART programs. [1] Recent data indicate that AIDS-related mortality has declined by 34% since 2010 – again largely driven by the steady scale-up of ART. [2] However, we are still far from achieving the targets for 2020 set by the joint United Nations programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), called the ’90-90-90 targets’. [2] The first target is to ensure that 90% of all people living with HIV are aware of their status. The second target is that 90% of those diagnosed receive sustained ART. And the third target means that 90% of those receiving ART have viral suppression. Mathematical models suggest that if we achieve the UNAIDS targets by 2020, a reduction of the global HIV incidence from the current level of 2 million to a level of 500,000 could be expected in 2020, and subsequently the end of the epidemic by 2030. These models are based on scientific evidence that, irrespective of the disease stage (i.e. CD4 count), ART initiation not only has individual therapeutic benefits but also prevents onwards HIV transmission. It is therefore strongly endorsed by WHO. [3-5]

This ‘Treatment for All’ strategy not only poses financial and human resource challenges, but also means that more asymptomatic patients will enter the HIV care cascade for whom the benefit of ART might not be evident, and who might therefore be less motivated to attend their nearest clinic for ART initiation and subsequent drug refills. Thus, the second UNAIDS target is often referred to as the Achilles heel of the 90-90-90 strategy. [6] In the case of community- or home-based HIV testing in sub-Saharan Africa, overall linkage to care rates after a positive HIV test are below 50% in the vast majority of studies. [7]

Same-day art initiation – a simple way forward?

The RapIT trial by Rosen and colleagues in 2016 demonstrated a possible innovative approach to deal with this Achilles heel: same-day ART initiation. [8] Subsequently, in 2017, WHO expanded the guidelines on ART initiation to focus on rapid initiation. [9] The RapIT trial, however, was conducted in a clinic-based setting and still used CD4 for ART initiation criteria.

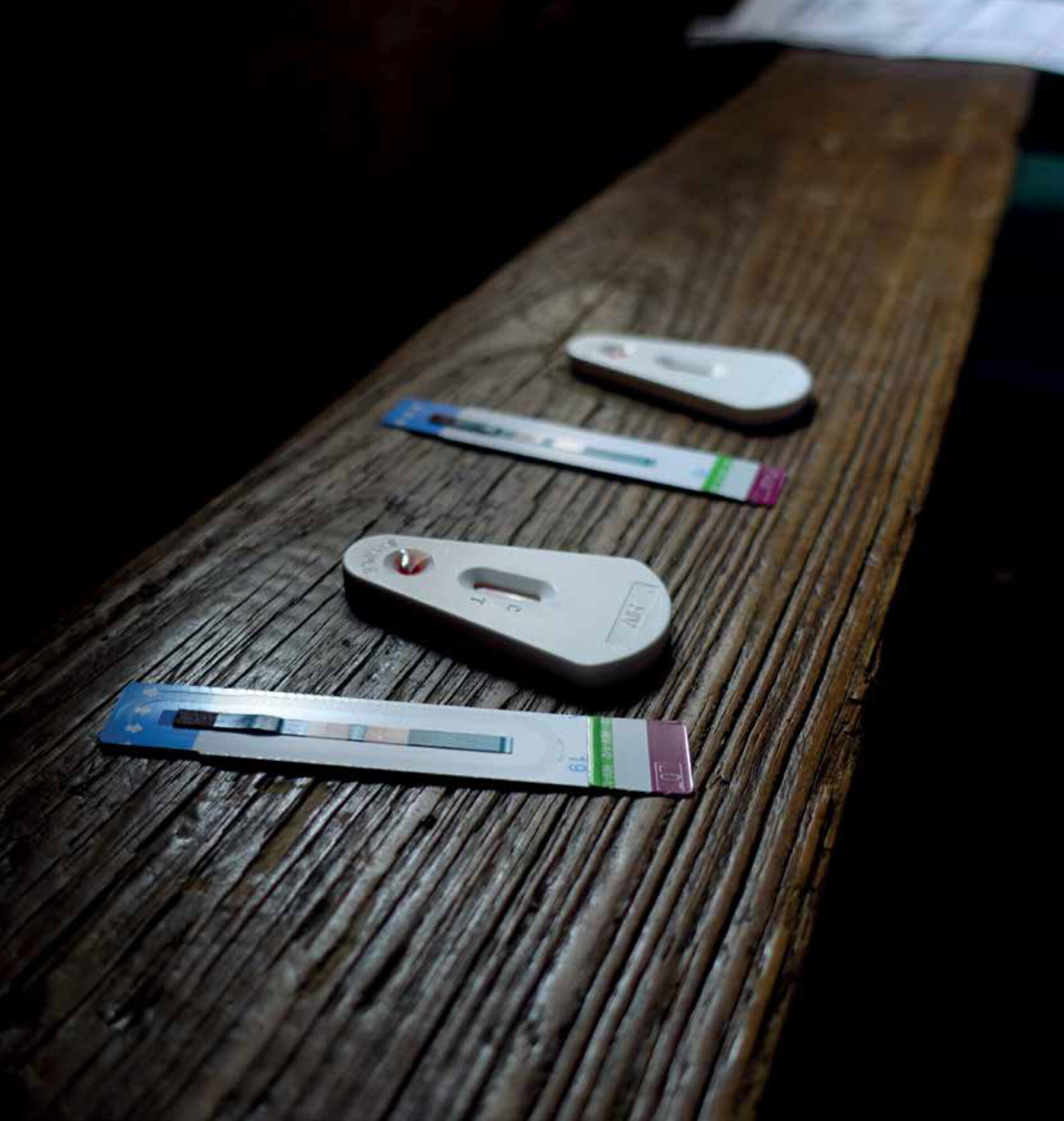

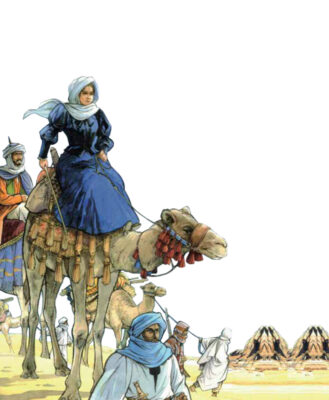

The first study to assess the effect of same-day ART initiation in the community – regardless of CD4 count – was the CASCADE study by our research group, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association. [10] This parallel-arm, open-label randomized clinical trial was conducted in Lesotho, which has the second-highest adult HIV prevalence globally (25.6%). More than 70% of Lesotho’s population lives in rural areas, which negatively affects engagement in care after home-based HIV testing. [11] Almost 300 adults from rural and urban areas, who tested positive for HIV during a home-based testing campaign and never received ART, were randomized to either receive the offer of same-day ART initiation on the spot or the usual referral to a nearby health facility. In the same-day initiation group, the nurse performed a clinical assessment, point-of-care baseline blood tests (CD4, creatinine, and haemoglobin), counselling, and a readiness assessment. If the patient agreed to being part of the study and was ready to start ART, a one-month supply of the standard first-line ART was dispensed. 97.8% of the patients in the same-day ART offer group were ready to start treatment the same day. The primary outcome measures were linkage to care at 3 months and viral suppression at 12 months. A significant improvement in 3-month linkage to care was observed (68.6% in the same-day group vs 43.1% in the usual care group, p<0.001) and, more importantly, higher rates of viral suppression at 12 months after enrolment (50.4% in the same-day group vs 34.3% in the usual care group, p=0.007), which indicates successful engagement in care. [10]

These results demonstrate the feasibility and effectiveness of same-day ART initiation in the community. Moreover, it shows that a simple intervention that lowers the first barrier in the HIV care cascade (linking after testing) can have a huge impact along the entire cascade until viral suppression.

A limitation of this study is that it excluded pregnant, breastfeeding women, those with advanced HIV disease, and people with active tuberculosis or other chronic conditions – groups that may benefit the most from rapid ART initiation. Furthermore, overall virologic suppression rates were still below the UNAIDS 90-90-90 targets, highlighting the need for enhanced and sustained efforts to engage people in care.

Vibra model – addressing the shortcomings of same-day art initiation

Our response to the challenges of sustained engagement in care after ART initiation in the community is called VIBRA (Village-Based Refill of ART), an innovative ART delivery model. There is increasing global consensus that new ART delivery models are needed, especially in rural settings that face shortages of doctors and nurses and limited financial resources. [12] These models should not only increase engagement in care but also be cost-effective without compromising quality of care, and have the potential to be replicated in similar settings. One promising approach is to further decentralize ART services and shift tasks to lay health personnel, i.e. drug adherence monitoring, TB screening, and psychosocial support in the community. WHO thus endorses the training of community health workers as a decentralization strategy, and UNAIDS launched a recruitment plan for 2 million community health workers in Africa. [13,14] Most countries in sub-Saharan Africa have some form of a community health worker program in place. A long-standing public sector cadre of lay health personnel, called village health workers (VHW), was introduced in 1978 in Lesotho with more than 4000 VHWs currently successfully operating in all districts. VHWs are members of and appointed by the community to provide a package of basic services at the household level, although they have no formal professional health education. They are elected by the village members, complete a 2-weeks training followed by periodic refresher courses, and are supported and supervised by staff from nearby health centres. They receive a monthly stipend of USD 20 from the Ministry of Health. VWH’s tasks are mostly preventive and include the promotion of antenatal care, education about hygiene, sanitation, nutrition, HIV testing and counselling, the referral of sick people to the health centre or hospital, the organization of community meetings, and tracing patients who are lost to follow-up. Specifically, regarding HIV service delivery, it has been shown that VHWs play a pivotal role in reducing stigma and discrimination. [15]

In close collaboration with a Swiss-based but locally long-standing active non-profit organization (SolidarMed) and other local stakeholders, we designed the VIBRA model, a differentiated ART delivery model that builds on the VHW program and uses SMS technology, addressing the challenge of long-term treatment adherence after same-day home-based ART initiation. Currently, we are running a large cluster-randomized trial in two districts of Lesotho in order to assess the VIBRA model. People living with HIV, who we find during a home-based testing campaign in rural villages, are offered ART initiation at home as performed in the CASCADE trial. In the intervention clusters, the newly initiated patients have the option of going to their VHW for ART visits and drug refills and to visit the health facility only once or twice per year for clinical follow-up and blood testing. Additionally, they receive automatically generated SMS messages, sent through a secured online platform. The platform is connected to the governmental district laboratory database with access to viral load results from all study districts. Apart from periodic standard treatment reminders (without explicitly mentioning HIV or HIV care), they may also receive personalised messages, depending on their viral load level. Patients with high viral load levels are asked to revisit the health facility as soon as possible in order to assess adherence to treatment, whereas patients with suppressed viral load levels can stick to their prolonged follow-up refill visit. (Study protocol in publication status. Project homepage: https://getonproject.wordpress.com/)

Conclusion

Effective, innovative and differentiated strategies are needed to improve the HIV care cascade, especially in rural settings. Same-day ART initiation and the VIBRA model will probably not be the magical solution to reach the UNAIDS targets globally, but they may be an important piece in solving the complex puzzle of scaling up ART programs. First results are expected by the end of 2019.

The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of his associated institutions (Swiss TPH / SolidarMed).

Our research in Lesotho:

www.swisstph.ch/en/projects/hiv-care-research-in-lesotho

There is increasing global consensus that new art delivery models are needed, especially in rural settings that face shortages of doctors and nurses and limited financial resources.

References

- UNICEF. Children and AIDS: Statisti-cal update. New York: UNICEF; 2017

- UNAIDS data 2018 [internet]. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2018. Available from: http://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/unaids-data-2018_en.pdf.

- The INSIGHT START Study Group. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy in Early Asymptom-atic HIV Infection. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(9):795-807. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1506816

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, and the HPTN 052 Study Team. Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:493-505.

- World Health Organization (WHO). Consolidated guidelines on the use of antiretroviral drugs for treating and preventing HIV infection; Recommenda-tions for a public health approach – Second edition June 2016 [internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2016. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/arv/arv-2016/en/

- Nachega JB, Uthman OA, del Rio C, et al. Addressing the Achilles’ Heel in the HIV Care Continuum for the Success of a Test-and-Treat Strategy to Achieve an AIDS-Free Generation. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014;59 (Suppl 1): S21-S27. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu299

- Ruzagira E, Baisley K, Kamali A, et al. The Working Group on Linkage to HIV Care. Linkage to HIV care after home-based HIV counselling and testing in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review. Trop Med Int Health. 2017 Jul;22(7):807-821. doi:10.1111/tmi.12888

- Rosen S, Maskew M, Fox MP, et al. Initiating Antiret-roviral Therapy for HIV at a Patient’s First Clinic Visit: The RapIT Randomized Controlled Trial. PLoS Med 13(5): e1002015. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002015

- World Health Organization (WHO). Guidelines for the managing advanced HIV disease and rapid initiation of antiretroviral therapy [internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2017. Available from: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/guidelines/advanced-HIV-disease/en/

- Labhardt ND, Ringera I, Lejone TI, et al. Effect of Offering Same-Day ART vs Usual Health Facility Re-ferral During Home-Based HIV Testing on Linkage to Care and Viral Suppression Among Adults With HIV in Lesotho: The CASCADE Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. March 2018. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.1818

- Labhardt ND, Motlomelo M, Cerutti B et al. Home-Based Versus Mobile Clinic HIV Testing and Counseling in Rural Lesotho: A Cluster-Randomized Trial. PLoS Med. 2014;11:e1001768

- Ehrenkranz PD, Calleja JM, El Sadr W, et al. A pragmatic approach to monitor and evaluate imple-mentation and impact of differentiated ART delivery for global and national stakeholders. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(3):e25080. doi:10.1002/jia2.25080

- World Health Organization (WHO). TASK SHIFTING: rational redistribution of tasks among health workforce teams. Global Recommendations and Guidelines [internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2017. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthsystems/TTR-TaskShifting.pdf

- UNAIDS and CSD endorse creation of 2 million CHWs in support of 90-90-90 [internet]. Cen-ter for Sustainable Development; 2017. Available from: http://csd.columbia.edu/2017/02/17/unaids-and-csd-endorse-creation-of-2-million-chws/

- Barr D, Odetoyinbo M, Mworeko L, et al. The leadership of communities in HIV service deliv-ery. AIDS Lond Engl. 2015;29 Suppl 2:S121-127. doi:10.1097/QAD.0000000000000727