Main content

Cerebral palsy (CP) is a disability that affects movement of the muscles, posture and tone. It is caused by brain damage that occurs during the prenatal period, perinatal period or in the first years of life.[1] CP is the major cause of childhood disability.[2]

The precise burden of CP in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC) is unknown, but it is estimated to be 2 to 2.5 per 1000 live births, which is 5 to 10 times higher than in high-income countries (HIC).[3] The majority of children with CP not only have motor impairment but also associated impairments including chronic pain, swallowing difficulties, intellectual disabilities, behavioural problems and epilepsy.[4] Around a third of patients with CP will never be able to walk and these children are also at great risk of malnutrition.[5]

In LMICs, diagnosis is often done at a late stage. This is mostly due to a lack of knowledge by health professionals and the lack of a structured screening procedure. This leaves many children with unrecognized disabilities and without appropriate intervention.[1,6] The delayed diagnosis and lack of rehabilitation leads to severe motor impairment.

Children with disabilities and their families in African countries are frequently excluded from society because of stigmatization. Most of these families are confronted with many social and economic challenges.[1] Having a life-long condition with great impairment has the potential to affect physical, psychological, cognitive and social functioning.[7] Those affected in LMICs face additional challenges because of poverty, which makes it more difficult to get access to health, education, food and basic needs, thus compromising quality of life for children with CP.[1,8]

Taking care of a child with CP has a big impact on the caregiver, and the needs of caregivers may often not be recognized. The special needs of a child with CP may add to the emotional, physical and financial strain inherent in raising children with a disability in a LMIC.[9] The long-term care is an extra burden on the well-being, marital relationships, and financial status of caregivers.[10,11] This leads to a low quality of life for caregivers who take care of a child with CP.[1,10,11]

In Malawi, the care that is given to (families with) children with CP is poorly organized and fragmented. Children suffering from malnutrition need to go to the malnutrition outpatient clinic (OPD), children with motor problems need to go to physiotherapy, and if you have epilepsy you need to go to the epilepsy clinic. These clinics are all on different days and there is no holistic approach to the patient. Due to restricted access to transportation, financial issues, and inability to move patients with severe CP easily, attending all these individual clinics is impossible for patients and their caregivers. One way to improve the quality of care for these children and their families may be to establish multidisciplinary care to address different aspects of care and support as required.

We describe our own experiences in Malawi, exploring the way forward in providing health care to children with cerebral palsy and their caregivers. To set up multidisciplinary care, we first had to assess and increase the existing knowledge of health workers on cerebral palsy and understand the situation of these families in their respective communities.

Setting

Mangochi District Hospital is a 400-bed hospital situated in a rural district where 88.9% of the population is categorized as the poorest households (International Wealth Index value <35).[12] (Figure 2) It is a referral hospital for 47 health centres and 4 community hospitals with a catchment area of 1.3 million people. The CP care that was offered previously was only a physiotherapy OPD. There were around 40-50 patients attending this OPD monthly. Because of the large catchment area, it was likely that many patients were not attending the clinic and were not receiving any CP care.

Increasing knowledge

Lack of knowledge among health workers is a big barrier for (early) identification and assessment of children with CP, which is why the first step of the programme was to increase knowledge. Every week we started doing ward rounds in the nursery of Mangochi District Hospital to identify children with birth asphyxia or prematurity. These are risk factors for developing CP, and the caregivers of these children are counselled to attend the CP clinic after 3 and 6 months to assess the child and to see if there are any early signs of CP. In addition to this, multiple lectures were given about CP in Mangochi District Hospital and in 13 selected health centres and community hospitals that are included in a pilot study for increasing quality of care for children with CP and their families.

Feedback received during these teaching sessions was that CP is not a condition that the health workers understood well. Not all health workers know about the different aetiologies, comorbidities and care that should be given. Most of the patients and caregivers were told that there was nothing they could do for their child and were sent home. During teaching sessions, these points were addressed and strengthened. After these sessions, we saw an increase of 73% in the number of patients attending the clinic.

Community

To get a better understanding of the situation in the communities around Mangochi District Hospital, we conducted a qualitative study to explore the knowledge, attitudes and perceptions of community leaders towards CP. It became clear that many families are in great financial distress due to the care for their child. The care for a child with this disability prevents the mother from going to the market or working on the farm. With 85% of the people in Malawi depending on farming for income, this places a large financial burden on the family, making it difficult for them to survive and meet basic needs. As a lay leader stated:

‘The presence of financial inactivity for both parents brings about a lot of problems and marital tension. The husband may want to leave the wife and remarry somebody else. This will pile more misery in the life of both the mother and her child with CP.’

Similarly, a sheikh stated:

‘These families with children with CP have no time to go and do something that may be beneficial financially, and also they lack funds that may support the child’s medical needs, and as a result, they may end up selling home properties to meet the medical needs of the child, and this puts them in a very difficult corner financially.’

Facilitators addressed by community leaders to improve the care for these children included a multidisciplinary care approach so patients can receive all the care at once and better counselling by health workers to increase understanding of the disease.

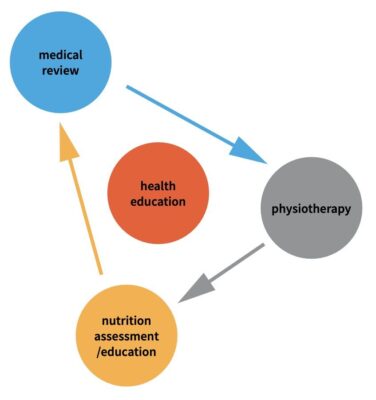

Multidisciplinary care

As a response, we came up with a project to increase the quality of life of children and caregivers with cerebral palsy by providing patient-centred care and a holistic approach that addresses their needs. The literature indicates that the most common physical problems that these children face are motor problems, intellectual disabilities, behavioural issues, communication issues, epilepsy and feeding problems (Figure 2). With a multidisciplinary OPD, we are addressing all these different issues at once, including: nutrition assessment, food supplements and counselling, physiotherapy with a special CP programme focusing on improving the ability to do daily activities, support with CP devices like special chairs and standing frames, and medical consultation and health education in which caregivers also have time to discuss their situation and get peer support.

The first responses after one month of providing multidisciplinary care are very promising. Caregivers say it is a relief that they can attend all health workers in one visit and that they have the feeling they are taken more seriously. The children attending the OPD do have untreated comorbidities: 47.6% of the patients have epilepsy of whom over 85% were not receiving any epileptics, and 33% of the patients showed signs of moderate or severe malnutrition. This OPD helps them to obtain better physical health overall. We hope this will lead to more possibilities for integration in the communities and to decreasing part of the burden on the caregivers.

References

- Donald, K. A., Samia, P., Kakooza-Mwesige, A., & Bearden, D. (2014). Pediatric cerebral palsy in Africa: a systematic review. Seminars in pediatric neurology, 21(1), 30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.spen.2014.01.001

- Oskoui, M., Coutinho, F., Dykeman, J., Jetté, N., & Pringsheim, T. (2013). An update on the prevalence of cerebral palsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Developmental medicine and child neurology, 55(6), 509–519. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.12080

- Cruz, M., Jenkins, R., & Silberberg, D. (2006). The burden of brain disorders. Science (New York, N.Y.), 312(5770), 53. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.312.5770.53b

- Eunson, P. “Aetiology and epidemiology of cerebral palsy”. Paediatrics and Child Health, Volume 22, Issue 9, 361 – 366

- Donkor, C. M., Lee, J., Lelijveld, N., Adams, M., Baltussen, M. M., Nyante, G. G., Kerac, M., Polack, S., & Zuurmond, M. (2018). Improving nutritional status of children with Cerebral palsy: a qualitative study of caregiver experiences and community-based training in Ghana. Food science & nutrition, 7(1), 35–43. https://doi.org/10.1002/fsn3.788

- Jahan, I., Muhit, M., Hardianto, D., Laryea, F., Chhetri, A. B., Smithers-Sheedy, H., McIntyre, S., Badawi, N., & Khandaker, G. (2021). Epidemiology of cerebral palsy in low- and middle-income countries: preliminary findings from an international multi-centre cerebral palsy register. Developmental medicine and child neurology, 63(11), 1327–1336. https://doi.org/10.1111/dmcn.14926

- Novak, I., Hines, M., Goldsmith, S., & Barclay, R. (2012). Clinical prognostic messages from a systematic review on cerebral palsy. Pediatrics, 130(5), e1285–e1312. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-0924

- Mohammed, F. M., Ali, S. M., & Mustafa, M. A. (2016). Quality of life of cerebral palsy patients and their caregivers: A cross sectional study in a rehabilitation center Khartoum-Sudan (2014 – 2015). Journal of neurosciences in rural practice, 7(3), 355–361. https://doi.org/10.4103/0976-3147.182778

- Moster, D., Wilcox, A. J., Vollset, S. E., Markestad, T., & Lie, R. T. (2010). Cerebral palsy among term and postterm births. JAMA, 304(9), 976–982. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2010.1271

- Davis, E., Shelly, A., Waters, E., Boyd, R., Cook, K., Davern, M., & Reddihough, D. (2010). The impact of caring for a child with cerebral palsy: quality of life for mothers and fathers. Child: care, health and development, 36(1), 63–73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2214.2009.00989.x

- Dambi, J. M., Jelsma, J., & Mlambo, T. (2015). Caring for a child with Cerebral Palsy: The experience of Zimbabwean mothers. African journal of disability, 4(1), 168. https://doi.org/10.4102/ajod.v4i1.168

- Global data lab, accessed on 23 February 2023, https://globaldatalab.org/areadata/profiles/MWIr104/