Main content

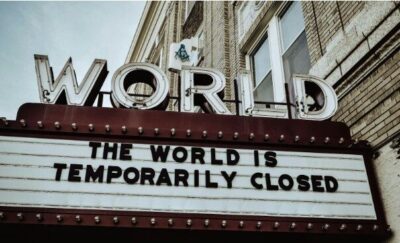

The global outbreak of SARS-CoV-2 has a firm grip on the world. As of mid-June 2020, there have been 8,700,000 confirmed cases and more than 460,000 deaths related to Covid-19. While many high-income countries have overcome the peak of the first wave of infections, the majority of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) are now awaiting the complete unfolding of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Meanwhile, global efforts to contain the spread of SARS-CoV-2 have indirectly challenged the continuity of many vital infectious disease control interventions for diseases that primarily affect LMICs, such as malaria, tuberculosis (TB) and HIV, as well as numerous vaccine-preventable illnesses. Lockdown measures aimed at mitigating the spread of Covid-19 are subsequently restricting the mobility of health workers, causing disruptions in supply chains due to border closures, and inhibiting the distribution of life-saving supplies and medicine to the community. The result is a ballooning crisis lurking in the shadow of the Covid-19 pandemic, one that will require significant and timely attention to prevent parallel epidemics of other infectious diseases in the months and years to come.

Malaria

Malaria is one of the world’s deadliest diseases, killing over 400,000 people yearly, 90% of whom are in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). The progress that has been made in containing malaria in SSA over the past two decades has been largely contingent on sustaining vector control programmes, some of which could be threatened by movement restrictions and the reallocation of resources aimed to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2.[1] Sudden lapses in the vector control program activities, like the distribution of insecticide-treated-bed nets (ITNs) and indoor residual spraying (IRS) of houses, would put millions of additional people at risk. A modelling study from Imperial College London presented a few potential outcomes that could occur if the distribution of ITNs were to be inhibited by lockdown measures, the worst of which would result in an additional 400,000 people dying of malaria globally within the next year, roughly doubling what was expected in the years prior to Covid.[2] This model does not take into account disruptions that could occur in access to treatment, chemoprophylaxis, or other forms of prevention, which could further precipitate the impact of malaria in SSA. Sustained interruptions in vector control interventions could additionally exacerbate the already growing issue of insecticide resistance in mosquitos across the region, a problem of immense gravity that threatens to reduce the efficacy of the two most prominent malaria control tools available, ITNs and IRS.

Vaccine preventable diseases

Measures to contain Covid-19 are also impacting current vaccination campaigns and routine vaccination programs across both high- and low-income countries. The global disruption of supply chains and travel restrictions have threatened to impede vaccine supplies, especially in rural areas in low resource settings.[3] Most mass vaccination campaigns have been temporarily suspended in an effort to mitigate the spread of SARS-CoV-2. While the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that routine vaccination should continue under infection control guidelines, many healthcare workers involved in such vaccination efforts have been re-allocated to the Covid-19 response, leaving health care facilities without sufficient staff to maintain immunisation services. Compounding these issues, fear of the virus has in some areas reduced willingness to seek out health services and contributed to problems of vaccine hesitancy.

More than half of the 129 countries where data is available indicate moderate to severe disruptions of child immunisation services in March and April of 2020, according to the WHO.[3] If the current trend continues, WHO, UNICEF and Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance estimate that more than 80 million children under the age of 1 could be at risk of contracting diseases such as diphtheria, measles and polio globally.[3] These disruptions could also severely impact child mortality, as demonstrated by a modelling study from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, which predicts that deaths prevented by sustaining routine childhood immunisation in Africa would highly outweigh the additional Covid related deaths attributed to infections acquired during health care visits.[4]

Tuberculosis and HIV

With approximately 1.5 million deaths in 2018, TB kills more people yearly than any other infectious disease. Successful treatment of TB requires rigorous case management and often close clinical supervision to provide daily doses of therapeutic drugs for around six months, both of which may prove difficult to maintain amidst movement restrictions and overwhelmed health care facilities. Lockdown measures in high-prevalence countries threaten to interrupt supply chains which would limit the availability of therapeutic drugs to maintain treatment. As with vector control in malaria, sudden cessation and restarting of treatment creates a heightened potential for drug resistance, which could in the future inhibit the last lines of defence against TB. A recent modelling study by the Stop TB Partnership, in collaboration with Imperial College London, predicted that a three-month lockdown could lead to an additional 6.3 million cases in the coming five years, causing 1.4 million more TB related deaths globally.[5]

The potential interruption of antiretroviral therapy (ART) and the reallocation of facility and community health workers are also major threats for the approximately 37.9 million people living with HIV globally. Modelling of even minor disruptions of ART drug supplies demonstrates the potential for considerable increases in HIV-related deaths and transmission.[6] Both TB and HIV rely heavily on community access to encourage routine testing, and to initiate and ensure the continuation of life-saving treatment. A lack of access for community health workers due to government-imposed lockdowns will cause limitations in condom distribution, peer education and case management that are likely to further contribute to disease progression and mortality in the future.

A narrow window of opportunity

If the goal of SARS-CoV-2 containment measures is to reduce mortality and prevent the collapse of health care systems, it will not be achieved by allowing a significant resurgence of other infectious diseases that are in some cases more deadly than Covid-19. As the first principle of medicine states do no harm, it is integral to consider the collateral damage that may be caused by lockdown measures in LMICs.[7] In these settings, many of the restrictions in their current form threaten to undermine decades of progress in combatting malaria, HIV, TB and vaccine preventable diseases. A surge in other infectious diseases on top of the Covid-19 crisis may push many of these already fragile health care systems and economies to their breaking point, limiting their ability to deal with other looming crises like the staggering rise in malnutrition and mass migration.[8]

The WHO has recognized that many nations, particularly in SSA, have a ‘window of opportunity’ to expand their disease control efforts while they still have a relatively low burden of Covid-19.[9] This could involve large campaigns to distribute insecticide treated bed nets, increase efforts to stockpile and distribute life-saving HIV and TB medication, and ensure that routine vaccinations are sustained during lockdown as an absolute priority. Finding ways to safely reintroduce community health workers could help to ensure the continuity of such programs throughout the duration of the lockdowns.

It is essential for the global health community to also acknowledge another important window of opportunity, the period directly following the lifting of lockdowns. Ensuring the restoration and expansion of program activities during this time period may have significant implications for infectious disease control in the future. This will involve increased active case finding efforts for TB and HIV, vaccine catch up programs, and efforts to improve and re-establish supply chains. With no promise of a Covid vaccine, LMICs cannot afford to wait to address the myriad of infectious diseases that are likely to remain endemic long after the pandemic subsides.

References

- Shretta R. Safeguarding the malaria endgame in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic. Centre for Tropical Medicine and Global Health [Internet]. 2020 Apr 25 [accessed 2020 Jul 5]. Available from: https://www.tropicalmedicine.ox.ac.uk/news/safeguarding-the-malaria-endgame-in-the-midst-of-the-covid-19-pandemic

- Sherrad-Smith E, Hogan AB, Hamlet A, et al. Report 18: the potential public health impact of COVID-19 on malaria in Africa. London: Imperial College London; 2020. 9 p. Report No.: 18

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization. At least 80 million children under one at risk of diseases such as diphtheria, measles and polio as COVID-19 disrupts routine vaccination efforts, warn Gavi, WHO and UNICEF. 2020 May 22 [accessed 2020 Jun 20]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/22-05-2020-at-least-80-million-children-under-one-at-risk-of-diseases-such-as-diphtheria-measles-and-polio-as-covid-19-disrupts-routine-vaccination-efforts-warn-gavi-who-and-unicef

- Abbas K, Procter SR, van Zandvoort K, et al. Routine childhood immunisation during COVID-19 pandemic in Africa: a benefit-risk analysis of health benefits of routine childhood immunisation against the excess risk of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 July 17; S2214-109X(20)30308-9. Online ahead of print

- Stop TB Partnership. The potential impact of the covid-19 response on tuberculosis in high-burden countries: a modelling analysis. [Internet]. 2020 May [accessed 2020 Jun 20]. Available from: http://www.stoptb.org/assets/documents/news/Modeling%20Report_1%20May%202020_FINAL.pdf

- Jewell B, Mudimu E, Stover J, et al. Potential effects of disruption to HIV programmes in sub-Saharan Africa caused by COVID-19: results from multiple models. 2020 May 11. Available from: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.12279932.v1. Online ahead of print

- Wehrens E, Bangura JS, Falama AM, et al. Primum non nocere: potential indirect adverse effects of COVID-19 containment strategies in the African region. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2020 May-Jun;35:101727. DOI:10.1016/j.tmaid.2020.101727. Epub ahead of print

- Roberton T, Carter ED, Chou VB, et al. Early estimates of the indirect effects of the COVID-19 pandemic on maternal and child mortality in low-income and middle-income countries: a modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020 Jul;8(7):e901-8

- World Health Organization [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization: WHO urges countries to move quickly to save lives from malaria in sub-Saharan Africa. 2020 Apr 23 [accessed 2020 Jun 20]. Available from:https://www.who.int/news-room/detail/23-04-2020-who-urges-countries-to-move-quickly-to-save-lives-from-malaria-in-sub-saharan-africa