Main content

Laparoscopic surgery (LS) has been one of the most revolutionising techniques in general surgery in the past decades. Starting in the 1930s as a diagnostic tool, it evolved into an operative procedure representing one of the first and most common forms of minimally invasive techniques. In Text box 1 the definition and procedures are summarised (from ref 2).

| Text box 1 “Laparoscopy is a minimally invasive surgery in the abdomen and/or pelvis used diagnostically or therapeutically. Small incisions are used to insert the laparoscope (a camera), surgical instruments like a grasper, and a tube to insert gas (typically CO2) in the abdomen to provide a clear view. It is usually performed under general anaesthesia, requiring the presence of a trained anaesthetist with appropriate equipment and drugs. Due to advanced surgical equipment, insufflation equipment etc, additional costs are involved and specialized training is needed.”[2] |

Due to its proven positive effects and wide availability, laparoscopy is one of the most commonly used technique in surgery in developed countries. The technique has many advantages for the patient including reduced blood loss, reduced chance of surgical site infection, reduced length of admission and of post-operative analgesia, and quicker return to work compared to open surgery. In addition, more efficient use is made of scarce resources. These advantages may be even more pronounced in low-resource settings where clean water, sanitation, and blood banks are scarce, and follow-up to detect common complications of surgery is often complex.[3] Similarly, efficient use of beds can be very beneficial in low-resource settings considering the great surgical demand and limited inpatient capacity. Furthermore, laparoscopy can be adequately used as a diagnostic tool and is cheaper than investing in computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).[4] Despite the obvious advantages, laparoscopy remains unavailable to 80% of the world’s population, mostly those living in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs).[5,6] In this article, we describe the feasibility and challenges of laparoscopic surgery in LMICs, illustrated with the experience in rural India.

Feasibility and adaptations

Minimally invasive surgery, especially laparoscopic surgery, offers clinical and economic benefits compared to open surgery, and it is feasible in low-resource settings if adaptive measures are taken. A systematic review by Wilkinson et al. (2021) identified seven key barriers: funding, availability and maintenance of equipment, local access to experienced laparoscopic trainers, lack of knowledge/ effective training curricula, practical opportunities for trainees, stakeholder dynamics, and surgical departmental structures.[7] Equipment is not always available because of costs and lack of funding, often relying on donations. The absence of companies producing and maintaining laparoscopic equipment in LMICs is another important barrier. In order to work around the limitations of laparoscopy in LMICS, adaptive strategies and measures can be followed, for example: approaching local soft drink manufacturers to supply affordable CO2, the re-usage of (disposable) instruments by sterilisation and repairs, the innovative use of cheaper instruments or substitutes for expensive equipment (e.g. sunlight used as a light source, cystoscope as a laparoscope) and gasless laparoscopy.[3] Also, the application of local or spinal anaesthesia is an alternative when general anaesthesia is resource-intensive. Laparoscopic training is often done in partnerships between surgical programmes in high-income countries (HICs) and LMICS, where the programmes from HICs facilitate training, equipment, and clinical guideline development. This model however is not sustainable, as often resources are exhausted when the training ends.[5] To overcome this barrier, innovative adaptations are implemented by developing training programmes with low-cost surgical simulations and skills labs, teleproctoring, internet based surgical videos, and training courses by local trainers. To enhance the feasibility of laparoscopy in LMICs, a collaboration between surgical societies and local and governmental institutions can provide policy, guidance, equipment, monitoring and incorporation of laparoscopic teaching in training curricula.[3,5,7]

The example of rural India

Rural surgeons in India began in 2001 with laparoscopic surgical procedures with equipment that was already available: the cystoscope.[8] Initially, it was used for diagnostic laparoscopy and for biopsies and, building on experience, was later used for procedures such as tubal ligation and appendectomies with the addition of a cystoscopic grasper. The lessons learnt from these laparoscopic surgeries were applied to provide minimally invasive surgeries. With the start of conventional laparoscopic surgery in rural areas, lack of general anaesthesia was a main concern because of costs involved and absence of trained staff and resources. To overcome these barriers, several methods were used.[9] Ether and an EMO machine (Epstein, Macintosh, Oxford machine, a temperature-controlled vaporiser) were used. As bottled CO2 is logistically difficult to get to a rural surgical facility in India, dental compressors (a machine that compresses atmospheric air) were used as a substitute. Disposable instruments were reprocessed. Although these measures led to an increase in laparoscopic surgeries, it did not prove to be sustainable as there were too many fluctuations in accessibility and affordable availability of gas and working equipment.

The Gas Insufflation Less Laparoscopic Surgeries (GILLS) proved to make a difference. Gasless laparoscopy is a form of mechanical lift laparoscopy, is relatively inexpensive in terms of equipment, and may be undertaken with spinal anaesthesia (Figure 1).[10] Spinal anaesthesia is three times less expensive than general anaesthesia and readily available. In addition, the learning curve for surgeons proved to be shorter compared to conventional laparoscopic surgeries, partly because long conventional instruments for open surgeries could be used without the risk of gas leakage. The International Federation of Rural Surgeons made teaching videos available, among others on low-cost technique for surgeries and GILLS cholecystectomies. The World Health Organization included the GILLS procedure in their compendium of innovative health care technologies for resource-poor settings[11] and steps were undertaken to further implement GILLS in rural India. The Association of Rural Surgeons of India organised workshops at medical colleges to promote and teach GILLS. The University of Leeds developed formal teaching for GILLS through the TARGET training programme. Finally, innovative proctorship programmes were established where faculty provides surgical training camps for rural surgeons at their local facility.

Impact

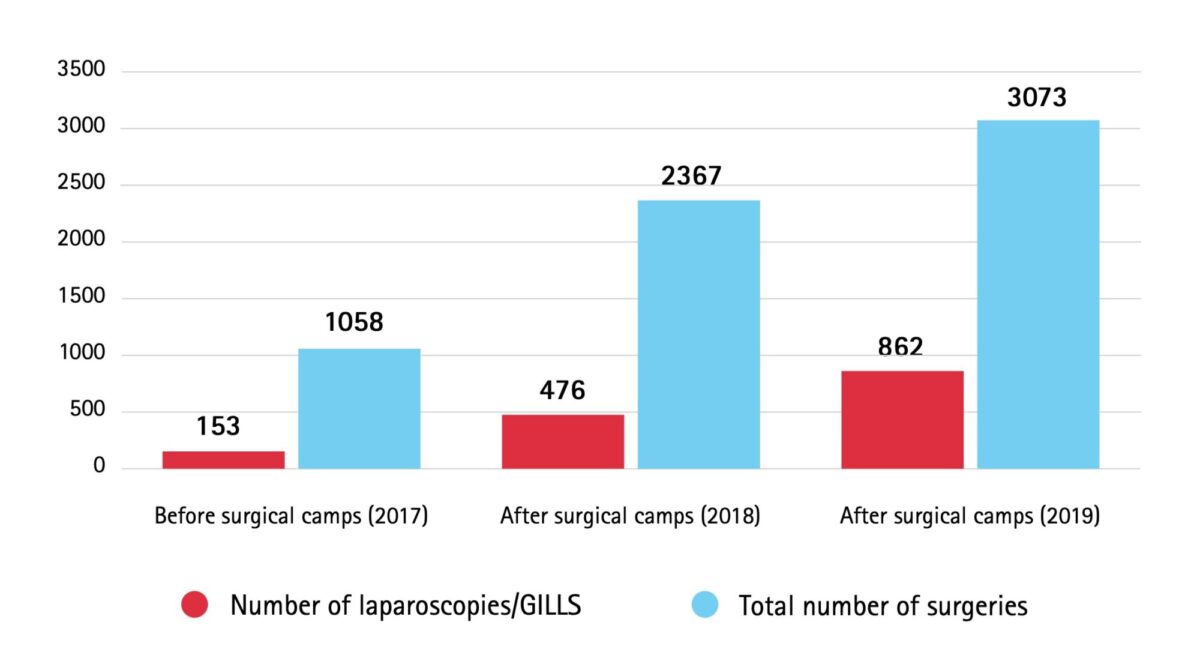

The proctorship programmes greatly improved surgical coverage. During the proctorship programme itself, 317 surgical procedures, mostly GILLS, per 100,000 people per year were carried out. Before the start of the programme, in 2017, the proportion of laparoscopic surgeries was 15%, which increased to 20% in 2018 and 28% in 2019 (Figure 2). Besides the surgical procedures done during the training, the total surgical volume increased between 2018 and 2019 from 2,880 to 3,739 per 100,000 people in the training target area. If this trend continues, 5,000 procedures per 100,000 population will be reached by 2030 – an important target set by The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery in 2015.[12]

In 2020 and 2021, the surgical training camps were affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. A positive side effect was the increase in digital consultations and supervised procedures through video calls, which are useful experiences for the future. Residents in surgery and rural surgeons are continuing to learn and perform laparoscopic surgeries, including GILLS, through proctorships including surgical training camps and training programmes at medical colleges.

Conclusion

With the increasing need for safe access to surgical care, minimally invasive surgeries including laparoscopic procedures play an important role, especially in rural settings. Implementing laparoscopy in LMICS, however, still faces great challenges. Overcoming those barriers is essential to gain clinical and economic benefits in surgical care. Therefore, innovative adaptive measures should be taken in infrastructure, equipment, technique and training. Training programmes (including local trainers and facilities) play a big role in safe implementation of laparoscopy but are still scarce and too reliant on HIC involvement, therefore not producing a sustainable training model. GILLS is an example of a high-potential affordable and available solution as seen by the uptake in rural India. To achieve sustainability and overcome barriers, collaboration of all (local) stakeholders is needed.

References

- Carr BM, Lyon JA, Romeiser J, et al. Laparoscopic versus open surgery: a systematic review evaluating Cochrane systematic reviews. Surg Endosc. 2019;33(6):1693-709. doi: 10.1007/s00464-018-6532-2

- Bolton WS, Aruparayil N, Quyn A, et al. Disseminating technology in global surgery. Br J Surg. 2019 Jan;106(2):e34-43. doi: 10.1002/bjs.11036

- Chao TE, Mandigo M, Opoku-Anane J, et al. Systematic review of laparoscopic surgery in low- and middle-income countries: benefits, challenges, and strategies. Surg Endosc. 2016 Jan;30(1):1-10. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4201-2

- Udwadia TE. Diagnostic laparoscopy. Surg Endosc. 2004 Jan;18(1):6-10. doi: 10.1007/s00464-002-8872-0

- Rosenbaum AJ, Maine RG. Improving access to laparoscopy in low-resource settings. Ann Glob Health. 2019 Aug 19;85(1):1-6. doi: 10.5334/aogh.2573

- Gnanaraj J, Rhodes M. Laparoscopic surgery in middle- and low-income countries: gasless lift laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2016 May;30(5):2151-4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-015-4433-1

- Wilkinson E, Aruparayil N, Gnanaraj J, et al. Barriers to training in laparoscopic surgery in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. Trop Doct. 2021 Apr 13:49475521998186. doi: 10.1177/0049475521998186

- Gnanaraj J. Diagnostic laparoscopies in rural areas: a different use for the cystoscope. Trop Doct. 2010 Jul;40(3):156. doi: 10.1258/td.2010.090322

- Jesudian G. Laparoscopic surgery in rural areas. ANZ J Surg. 2007 Sep;77(9):799-800. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-2197.2007.04235.x

- Mishra A, Bains L, Jesudin G, et al. Evaluation of gasless laparoscopy as a tool for minimal access surgery in low-to middle-income countries: a phase II noninferiority randomized controlled study. J Am Coll Surg. 2020 Nov;231(5):511-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2020.07.783

- Gnanaraj J. Single incision gasless laparoscopic surgical equipment. In: World Health Organization. WHO compendium of innovative health teachnologies for low-resource settings, 2016-2017. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2018. p. 72 [65]

- Meara JG, Leather AJM, Hagander L, et al. Global Surgery 2030: evidence and solutions for achieving health, welfare, and economic development. Lancet. 2015 Aug 8;386(9993):569-624. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60160-X