Main content

Leprosy (also called Hansen’s Disease) is a communicable disease caused by Mycobacterium leprae. It has a long incubation time, on average around five years, but it can also be up to twenty years or more. The disease affects the skin and peripheral nerves and can cause permanent damage to the skin, nerves, face, hands and feet. Untreated leprosy can lead to impairment, disabilities and social exclusion. Stigma and discrimination are often associated with leprosy and define the disease to a large extent.

Transmission is most likely through droplets from the nose and mouth during prolonged and close contact with untreated leprosy patients, but zoonotic sources are also possible, notably armadillos in South America and the southern states of the United States of America. [1] Diagnosis of leprosy is primarily clinical. Early detection of cases is important to interrupt spread of infection and prevent disability. Multidrug therapy (MDT) is available for six or twelve months combining dapsone, rifampicin and clofazimine, depending on the classification of the disease. Paucibacillary leprosy (PB) is treated for six months and multibacillary leprosy (MB) for twelve months.

Case management includes periodic monitoring, detection and treatment of leprosy reactions, which are immunological phenomena including inflammation of peripheral nerves, fever and skin eruptions causing substantial morbidity and nerve damage. Prevention of disability, wound care, and management of disability (including self-care) are essential components of the care for those affected by the disease. In addition, rehabilitation services provide improved functioning of the individual in the community. Counselling, psychological aid, and health education are crucial to support leprosy patients, their families, and the communities they live in. For comprehensive information about all aspects of leprosy, refer to the online International Textbook of Leprosy. [2]

Current epidemiological situation

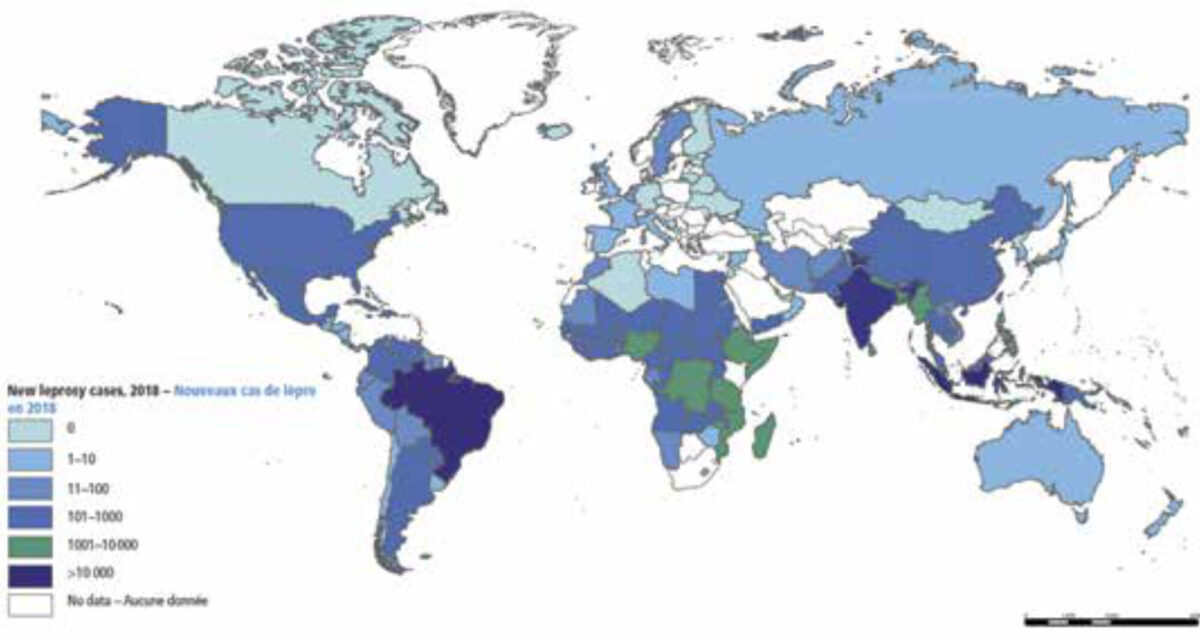

In 2018, the number of new leprosy cases was 208,619 of which approximately 16,000 were children younger than fifteen years of age. [3] Also, over 11,000 of the new cases had visible deformity of hands, feet and face (indicated as grade 2 disability). Cases were reported from 159 countries, with 80% of the burden occurring in India, Brazil and Indonesia. Figure I shows the geographical distribution of new leprosy cases in 2018.

The global trend in leprosy new case detection since 1985 is presented in Figure 2. The trend was remarkably static up to the year 2001, with a peak around the year 2000, then fell dramatically between 2001 and 2005, and has levelled off since 2006. The most important factor contributing to the fast downwards trend between 2001 and 2005 was the decline in leprosy control activities following the declaration by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2000 that leprosy was eliminated. The official term was “elimination as a public health problem”, [4] defined as a prevalence of less than one per 10,000 population at the world level. But most people, including governments, conveniently concluded that leprosy had disappeared altogether and did not need further attention (and funds). Hence the sharp reduction in case finding. The stabilization of the new case detection at just over 200,000 cases annually indicates that transmission of M. leprae is continuing unabated, posing an enormous challenge to leprosy control.

The way forward

The declaration by the WHO in the year 2000 that leprosy was ‘eliminated’ was counterproductive. Since then, the WHO has introduced more concrete and attainable targets which focus on impact of the disease in terms of grade 2 disability in new cases, in particular among children, and on legal issues, such as abolishment of laws allowing discrimination of the basis of leprosy. [5] For 2030, the WHO is setting an ambitious target of reducing the incidence (new case detection) of leprosy by 70%, with emphasis on substantially reducing new child cases (as a proxy for recent transmission) and new cases with grade 2 disability (as a proxy for detection delay). In the field of leprosy, an overall target of ‘zero leprosy’ has been embraced by the WHO, the International Federation of Anti-Leprosy Associations (ILEP), Novartis Foundation, the Sasakawa Health Foundation, and the International Association for Integration, Dignity and Economic Advancement (IDEA), indicating zero disease, zero disability, zero discrimination, and zero stigma (https://zeroleprosy.org/).

New preventive strategies

Leprosy control has traditionally been based on early case detection and treatment with MDT. Apart from health education and leprosy awareness campaigns, there were no preventive measures available. It was hoped in the 1990s that through the strategy of timely detection of cases and provision of MDT for patients, the transmission of M. leprae in the community could be interrupted, leading to a decline in leprosy incidence. Unfortunately, this has not been the case, as shown in Figure 2. Vaccines for leprosy have not been successful to date, but fortunately the BCG vaccine against tuberculosis also provides some protection against leprosy. [6] An important innovation has been the introduction of post-exposure chemoprophylaxis (PEP) for household and other (close) contacts of leprosy patients. A randomized controlled trial had shown that single-dose rifampicin (SDR) given once to household contacts, neighbours and social contacts reduces their risk of leprosy by approximately 60%. [7] Implementation studies have shown that PEP with SDR is feasible and well-accepted by patients, contacts and health workers in different health care settings. [8] Modelling studies have indicated its potential impact on transmission of M. leprae in endemic populations. [9] This intervention was included in the 2018 WHO Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy and is currently being introduced in many countries. [10]

Opportunities and challenges in leprosy

Leprosy is now included in the list of neglected tropical diseases (NTDs). This has drawn the attention of funding agencies outside the traditional field of leprosy, such as the Novartis Foundation, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the European and Developing Countries Clinical Trials Partnership (EDCTP). This has invigorated research into new diagnostics for disease and infection, [11] vaccines, enhanced PEP regimens, epidemiological tools such as geographic information systems (GIS) for identifying leprosy ‘hotspots’, surveillance of anti-microbial resistance, and alternative drugs and drug regimens for MDT.

The outlook for achieving zero leprosy in the coming decades is better than ever before, but it is admittedly very ambitious. It can only be reached if all leprosy endemic countries enhance their leprosy control activities to include: 1) active case finding strategies such as improved diagnosis; 2) contact screening; and 3) implementation of PEP. The proposed reduction in new case detection of 70% in 2030 is theoretically attainable if these interventions are introduced widely. [12]

However, there is also an important threat. With the waning of interest in leprosy since the year 2000 and the integration of the disease into the regular health systems, the number of medical doctors and health workers at the primary care level with experience in diagnosing and treating leprosy has decreased substantially all over the world. Expertise is being lost and will be difficult to build up again. Seasoned leprologists and leprosy researchers are retiring and not being replaced sufficiently by young doctors and scientists with interest in leprosy. There is a need for fresh ‘blood’, and hopefully young tropical doctors will be encouraged by this article to take interest in the fascinating topic of leprosy with its many challenges in the area of clinical medicine, public health, and social inclusion. The next generation needs to realize the ambition of a leprosy-free world in the decades to come.

Conflicts of interest: none

References

- Truman RW, Singh P, Sharma R, et al. Probable zoonotic leprosy in the southern United States. N Engl J Med. 2011 Apr 28;364(17):1626-33.

- International Textbook of Leprosy. 2018. Available from: https://internationaltextbookofleprosy.org/.

- WHO. Global leprosy update, 2018: moving towards a leprosy-free world. Weekly epidemiological record. 2019 Aug 30;35/36(94):389-412.

- World Health Organization. Guide to eliminate leprosy as a public health problem. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2000. 106 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/lep/resources/who_lep_97.7/en/.

- World Health Organization. Global Leprosy Strategy 2016-2020: accelerating towards a leprosy-free world. Cooreman EA, editor. New Delhi: WHO SEARO/Department of Control of Neglected Tropical Diseases; 2016. 20 p. Available from: https://www.who.int/lep/resources/9789290225096/en/.

- Duthie MS, Gillis TP, Reed SG. Advances and hurdles on the way toward a leprosy vaccine. Hum Vaccin. 2011 Nov;7(11):1172-83.

- Moet FJ, Pahan D, Oskam L, et al. Effectiveness of single dose rifampicin in preventing leprosy in close contacts of patients with newly diagnosed leprosy: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2008 Apr 5:336 (7647):761-4.

- Steinmann P, Cavaliero A, Aerts A, et al. The Leprosy Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (LPEP) programme: update and interim analysis. Lepr Rev. 2018;89(2):102-16.

- de Matos HJ, Blok DJ, de Vlas SJ, et al. Leprosy new case detection trends and the future effect of preventive interventions in Pará State, Brazil: a modelling study. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Mar;10(3). DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004507.

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the diagnosis, treatment and prevention of leprosy. New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2018. 106 p. Available from: https://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/en/m/abstract/Js23543en/.

- Roset Bahmanyar E, Smith WC, Brennan P, et al. Leprosy diagnostic test development as a prerequisite towards elimination: requirements from the user’s perspective. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2016 Feb;10(2). DOI:10.1371/journal.pntd.0004331.

- Medley GF, Blok DJ, Crump RE, et al. Policy lessons from quantitative modeling of leprosy. Clin Infect Dis. 2018 Jun 1;66(suppl_4):S281-S5.