Main content

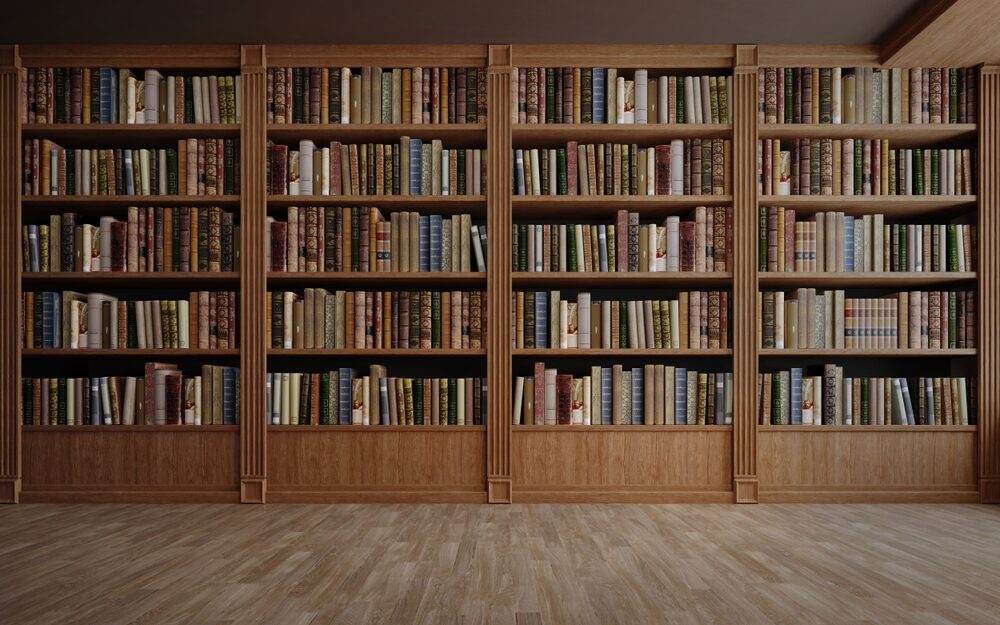

The world stands before the biggest threat to global health in the 21st century.[1] Climate change will have far reaching consequences, probably further than we can now foresee. The monumental Paris agreement has kept the hope alive to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius. Recent developments, however, have put this on hold. With a remaining carbon budget that will be spent in nine years, the urgency of emission mitigation steps is clear.[2] According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), around 23% of all global deaths are attributable to environmental risk factors, and up to 26% of all under-age-five deaths could be prevented by removal of these environmental risks; see Figure 1 for a breakdown in burden of disease by age.[3]

Already, in 2003, the worrying effects of climate change on child health were reported by Bunyavanich et al.[4] The researchers explain three pathways via which climate change will negatively impact child health: through environmental changes (e.g. respiratory disease and skin malignancies), through direct effects of extreme weather (e.g. heat stroke and drowning), and through ecological changes (e.g. increased malnutrition and allergies). In the Climate Change Risk Assessment (CCRA) published by WHO in 2014, an additional annual mortality of 250,000 people is expected by 2030 due to climate change. Around 84% of this mortality will occur in children in low-income countries due to undernutrition, malaria, dengue and diarrheal disease. Besides the additional mortality, the growth of millions more children will become stunted with far-reaching consequences.[5]

In this paper, a literature review is presented on the effects of climate change on child health in Malawi. The work was done in the context of a Master of Science thesis in International Health. Malawi is a low-income country that is already experiencing negative effects of climate change, for example from increased extreme weather events. Malawi was used as a case study due to its success in reaching Millennium Development Goals 4 (reducing child mortality) a few years ahead of its target.[6]

Methods

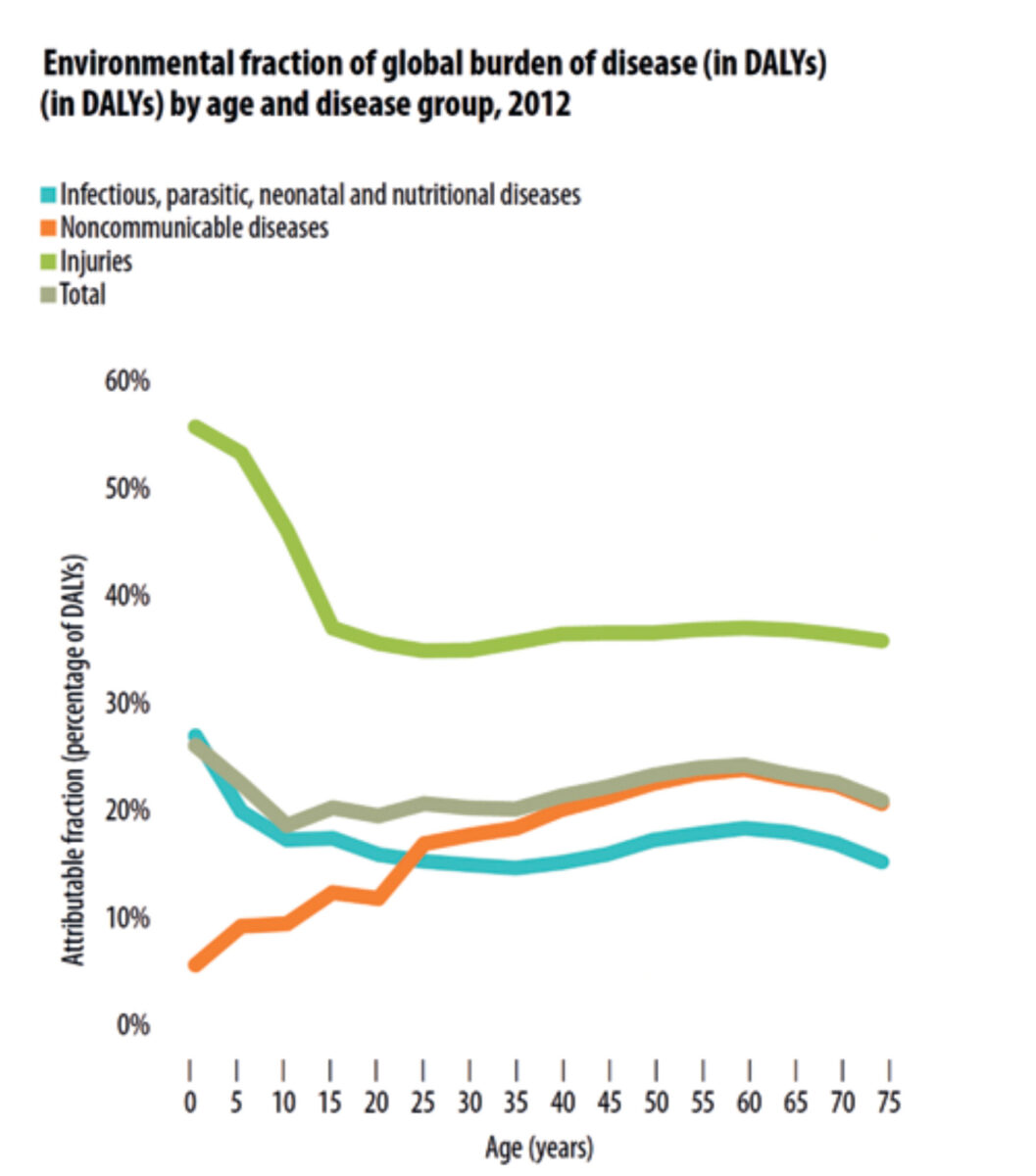

A literature review was performed to analyse the effects of climate change on child health in Malawi. Due to the large scope of the effects of climate change on health a focus was put on infectious diseases, undernutrition and air pollution. The expanded framework on climate change and child health published by Helldén et al was used (Figure 2).[7]

Results

Climate change

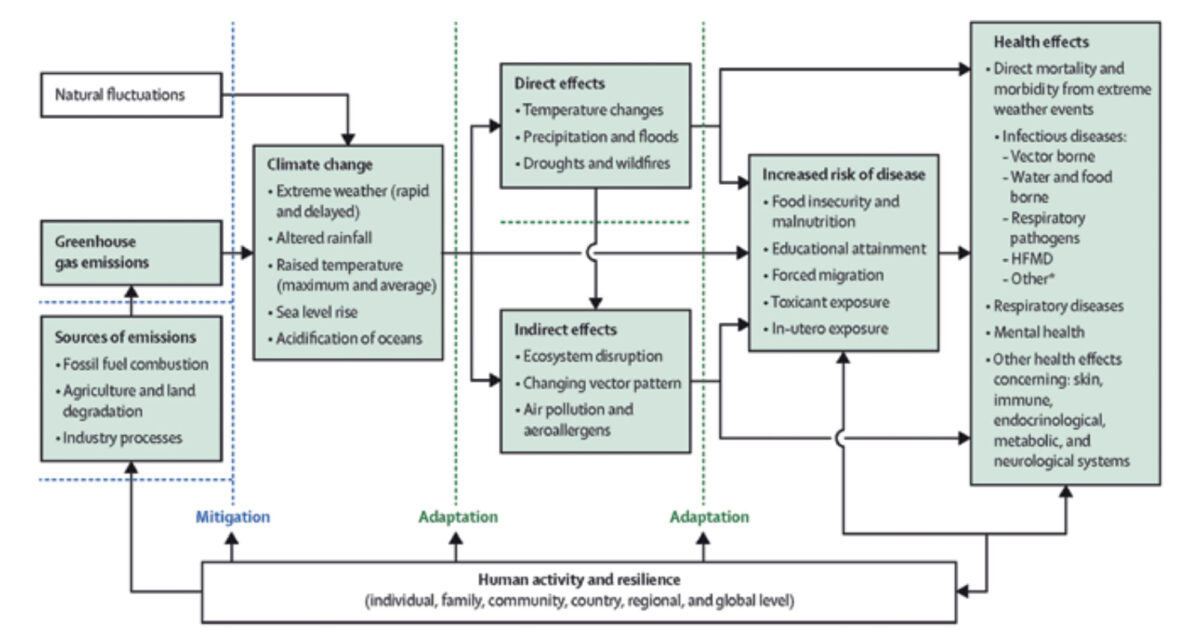

The effects of climate change on Malawi will primarily occur through increased temperature, rainfall variability and extreme weather events. By the end of this century, mean temperature could increase by 2.3 – 6.3 degrees Celsius. Although there is considerable uncertainty considering rainfall projections, mean annual rainfall is projected to stay the same but the number of rainy days will decrease and the amount of rain per day will increase, leading to longer dry spells and an increase in days with heavy rains.[8] Extreme weather events have significantly increased over time [9] and have affected the lives of many people, recently mostly through floods (Figures 3 and 4).[10,11]

Direct and indirect effects

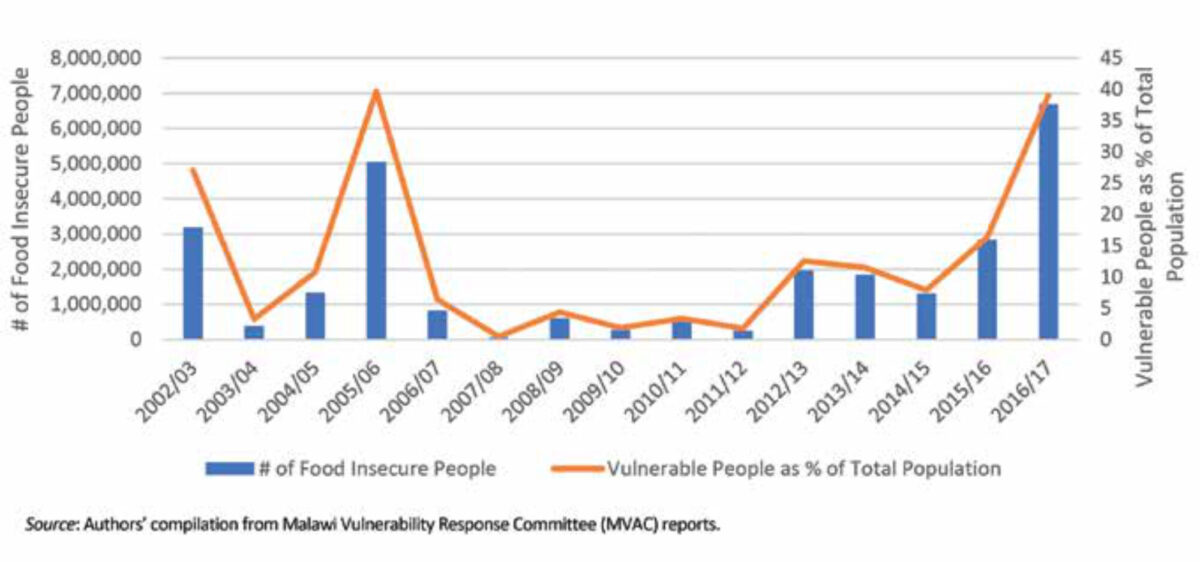

Woodland degradation due to land clearance for agriculture and wood fuel harvesting leads to soil erosion and an increased vulnerability to these extreme weather events.[12] This has resulted in reduced crop yield, loss of livestock, increased food prices, internal displacements, damaged (health and education) infrastructure, direct casualties, reduced access to safe drinking water, and spread of waterborne diseases.[13,14] During the next El Nino phase, which will happen in the next few years, Malawi will again be particularly prone to prolonged droughts and increased heat. The last severe episode resulted in a 30%-40% decrease in maize production and 6.7 million food-insecure people (Figure 4).[11]

The longer warm conditions could raise the incidence of malaria during 7-9 months rather than the historical 3-4 months (January-April) and also expand the area affected towards the highlands.[15] The higher temperatures could also affect plant pathogens and could make the environment more suitable for cattle diseases like “East Coast Fever” caused by Theileria parva. [15,16]

Air quality is affected by climate change in several ways. Increased temperatures will increase ground level ozone levels and aeroallergens, which are known triggers for childhood asthma. Due to increased evapotranspiration and decreased precipitation, there is an increase in particulate matter (PM), ie. air pollution of particles with a diameter of ≤ 2.5 microns (PM2.5). This is due to smoke from forest fires and wildfires and increased wind-blown dust due to drought. Children under 12 could be particularly affected by this since their lungs are still developing. They spend more time outdoors, are more active, and breathe twice as fast as adults.[17] Pregnant women and infants are also at increased risk of morbidity and mortality from air pollution. Maternal exposure to PM air pollution and ozone was associated with Low Birth Weight (LBW), Small for Gestational Age (SGA), and Preterm Birth (PTB). Postnatal exposure to air pollutants (PM, ozone and nitrogen dioxide) has been associated with increased infant mortality.[18] Unfortunately, in contrast to household air pollution, no studies on ambient air pollution targeted children in Malawi.

Increased risk of disease

The national and household food insecurity created by the increased temperature and extreme weather events lead to more stunting and acute malnutrition.[9,14] The large number of internally displaced people in the aftermath of these extreme weather events leads to increased vulnerability to infectious diseases: routine vaccination services are disrupted, the large number of people moving may inadvertently spread diseases, there are insufficient mosquito nets, more risk of diarrhoeal disease because of insufficient WASH facilities, exposure to sexual and gender based violence, and decreased access to primary care facilities due to infrastructure damage and unavailability. After the floods of 2019, for example, an estimated 460,000 children lacked basic supplies like food, water and access to toilets.[19] Another example is the aftermath of the recent storm Freddy that washed away houses, crops and infrastructure, and will likely lead to a worsening of the ongoing cholera epidemic.[20]

Due to climate change, the distribution and burden of disease by infectious diseases is also expected to change. The incidence of malaria, cholera, dysentery, scabies and schistosomiasis is expected to increase in Malawi. For viral vector borne diseases, the burden of disease is expected to increase, but so far there have been no significant outbreaks of chikungunya, Zika or yellow fever, and no outbreaks have been reported of dengue in the past 10 years in Malawi.[21] In February 2022, Malawi declared an outbreak of wild poliovirus type 1, the first outbreak in Africa in five years, but the reason for this resurfacing is multifactorial.

Child health effects

Besides the direct effects of morbidity and mortality from extreme weather events, climate change will affect child health and development in multiple ways: increased food insecurity, limited poverty reduction, forced migration, reduced access to WASH facilities and healthcare / quality of healthcare, decreased educational attainment, air pollution, direct morbidity and mortality, and increased risk of infectious diseases. Little is known about the effect of potential increases of in- and ex utero exposure to toxicants and pollutants and increased temperatures on perinatal outcomes and the development of children in Malawi. In a recent systematic review, only two studies were published on mental health in Sub-Sahara Africa in Namibia and Nigeria describing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and focussing on floodings.[22]

Limitations

Limited studies were found studying the effect of heat waves on infant / child mortality in low-income countries. CCRA studies by WHO have had a limited scope and have not studied the effects of heat stress on children. Limited studies were found on the effects of ambient air pollution on mothers, new-borns and children. Limited studies were found on the effect of temperature increase on educational attainment in low-income settings. Limited studies were found studying the effects of increased temperature and/or acidification on the inland lakes of Malawi and thus its food and water supply.

Conclusion

From what we know at this moment, climate change is already affecting child health in a negative way in Malawi. There are considerable knowledge gaps which limit our ability to quantify the multitude of effects for low-income countries. High-income countries have an obligation, from an equity and from a climate justice perspective, to assist low-income countries in addressing these knowledge gaps and in developing effective adaptation policies.

References

- Costello A, Abbas M, Allen A et al. Managing the health effects of climate change. Lancet and University College London Institute for Global Health Commission. Lancet. 2009;373(9676):1693–733. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60935-1

- Friedlingstein P, O’Sullivan M, Jones MW et al. Global Carbon Budget 2022, Earth Syst. Sci. Data, 2022, 14, 4811–4900, https://doi.org/10.5194/essd-14-4811-2022

- Prüss-Ustün A, J Wolf, C Corvalán et al. Preventing disease through healthy environments: A global assessment of the environmental burden of disease. World Health Organisation [Internet 2016, cited 2023 April 11] Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241565196

- Bunyavanich S, Landrigan CP, McMichael AJ et al. The impact of climate change on child health. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(1):44–52. https://doi.org/10.1367/1539-4409(2003)003%3C0044:TIOCCO%3E2.0.CO;2

- World Health Organisation. Quantitative risk assessment of the effects of climate change on selected causes of death, 2030s and 2050s. [Internet, September 2014, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241507691

- Kanyuka M, Ndawala J, Mleme T et al. Malawi and Millennium Development Goal 4: a Countdown to 2015 country case study. Lancet Glob Health. 2016 Mar;4(3):e201-14. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2214-109x(15)00294-6

- Helldén D, Andersson C, Nilsson M, et al. Climate change and child health: a scoping review and an expanded conceptual framework. Lancet Planet Heal. 2021;5(3):e164–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2542-5196(20)30274-6

- Mittal N, Vincent K, Conway D, et al. Future climate projections for Malawi. Future Climate for Africa [Internet October 2017, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://www.futureclimateafrica.org/wpcontent/uploads/2017/10/2772_malawi_climatebrief_v6.pdf

- Government of Malawi – Ministry of Forestry and Natural Resources. The Third National Communication of the Republic of Malawi to the COP of the UNFCCC. [Internet February 2021, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://unfccc.int/documents/268340

- The World Bank Group. Climate Change Knowledge Portal – Country Malawi – Vulnerability [Internet, cited 2022 July 15]. Available from: https://climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org/country/malawi/vulnerability

- Botha, BN, Nkoka, FS, Mwumvaneza, Valens. Hard Hit by El Nino: Experiences, Responses and Options for Malawi. The World Bank, Washington, DC. [Internet May 2018, cited 2023 April 11] Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/30037

- The World Bank. Malawi Systematic Country Diagnostic: Breaking the Cycle of Low Growth and Slow Poverty Reduction [Internet December 2018, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/31131

- World Bank Group. Malawi Country Environmental Analysis. [Internet 2019 January, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://hdl.handle.net/10986/31326

- Government of Malawi. Malawi 2015 Floods Post Disaster Needs Assessment Report [Internet March 2015, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://reliefweb.int/report/malawi/malawi-2015-floods-post-disaster-needs-assessment-report

- IFRC Climate Centre. Climate Change Impacts on Health: Malawi Assessment. [Internet April 2021, cited 2023 April 11] Available from: https://www.climatecentre.org/wp-content/uploads/RCRC_IFRC-Country-assessments-Malawi_Final3.pdf

- Olwoch JM, Reyers B, Engelbrecht FA et al. Climate change and the tick-borne disease, Theileriosis (East Coast fever) in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Arid Environments 2008;72(2):108-20. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2007.04.003.

- UNICEF. Unless we act now: The impact of climate change on children. [Internet November 2015, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/reports/unless-we-act-now-impact-climate-change-children

- Schraufnagel DE, Balmes JR, Cowl CT et al. Air Pollution and Noncommunicable Diseases: A Review by the Forum of International Respiratory Societies’ Environmental Committee, Part 1: The Damaging Effects of Air Pollution. Chest 2019;155(2):409–16. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chest.2018.10.042

- UNICEF Malawi. Annual Report 2019, page 38 [Internet, July 2020, cited 2023 April 11]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/malawi/reports/unicef-malawi-annual-report-2019

- UNICEF. Children at risk of cholera in aftermath of cyclone Freddy. [Internet, March 2023, cited 2023 April 17]. Available from https://www.unicef.org.press-releases/children-risk-cholera-aftermath-Cyclone-Freddy

- Adam A, Jassoy C. Epidemiology and Laboratory Diagnostics of Dengue, Yellow Fever, Zika, and Chikungunya Virus Infections in Africa. Pathogens. 2021 Oct 14;10(10):1324. Available from: https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens10101324

- Rother HA, Hayward RA, Paulson JA et al. Impact of extreme weather events on Sub-Saharan African child and adolescent mental health: The implications of a systematic review of sparse research findings. Journal of Climate Change and Health 2022;5:100087. Available from: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100087