Main content

Many acutely ill or injured adults and children in Africa seek care every day. Frontline providers manage patients with acute problems like injuries, infections, stroke, asthma and complications of pregnancy. These acute presentations unfortunately contribute to a high mortality and morbidity. Health-care provision on the continent has historically focussed most on the classic burden of disease such as elective chronic care e.g. HIV/AIDS programs, nutritional care, elective surgery etc. It seems a growing burden of emergency presentations is not being provided for sufficiently. In response, in 2018 the WHO launched the Global Emergency and Trauma Care Initiative to provide a struc-tured framework to address this issue.[1]

The problem

Health and well-being in Africa is characterized by a unique and evolving triple burden of disease as well as a lack of access to healthcare. This combination contributes to the fact that it is the continent with the lowest life expectancy by far. [2]

The triple burden [3]

Communicable diseases, poverty and malnutrition characterize the first burden of disease, classically representing the majority of years of life lost in Africa. [4] These conditions can lead to acute life-threatening presentations such as sepsis and dehydration, which have a very good prognosis if treated adequately and in time. The second burden is non-communicable diseases (NCDs) and mental health. NCDs in Africa almost doubled the percentage of total deaths attributed to them in the period from 2008 to 2013. [5] These chronic lifestyle diseases such as cardiovascular disease, lung disease and diabetes typically present as life-threatening acute exacerbations such as diabetic ketoacidosis, asthma/ COPD exacerbation, stroke and heart attacks. The third burden is perhaps the most characteristic of the continent: accidents, violence and war. Specifically, trauma as a consequence of road traffic accidents (RTAs) and interpersonal violence causes almost double the amount of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) in Africa compared with the rest of the world. [6] Other major causes are burns and drowning. [7] Africa is the only WHO region where the percentage change in age-standardized road injury DALY rate increased over the period 1990–2013. [7]

Lack of access to emergency care

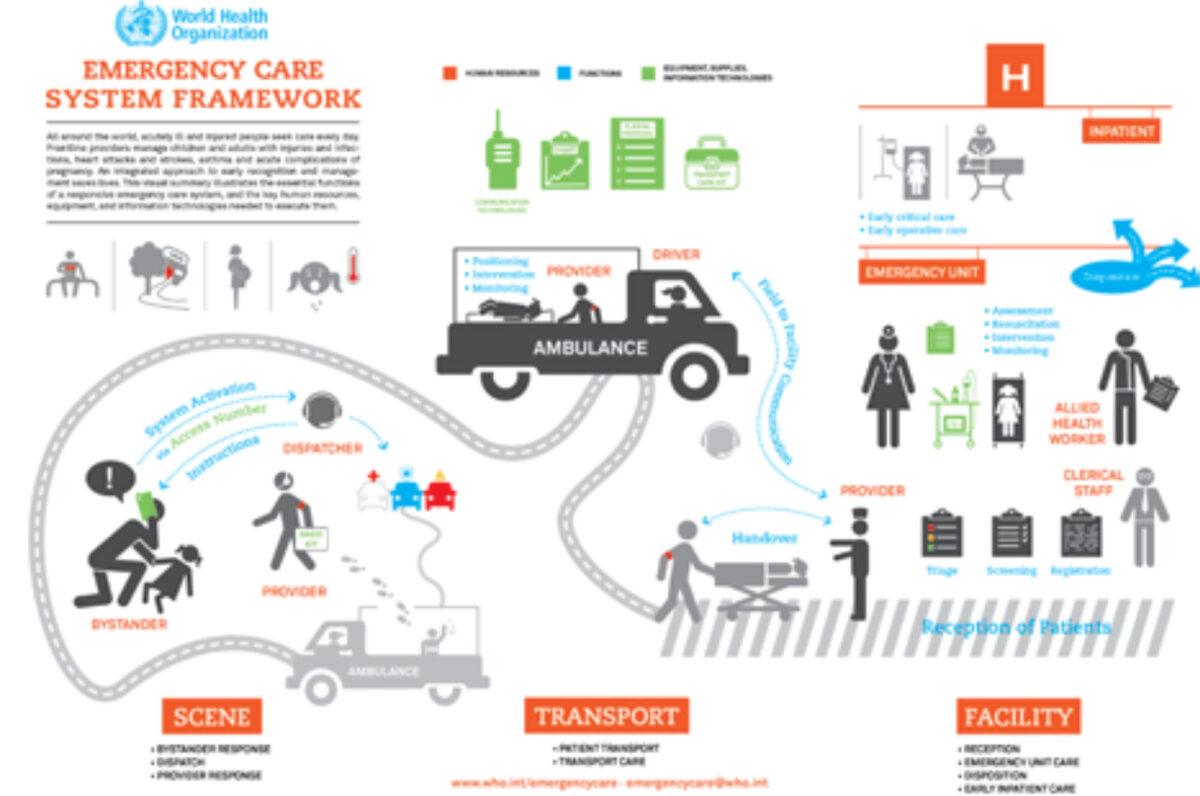

There are many obstacles to healthcare access in an emergency, especially in the rural areas of the continent. It starts with a lack of bystander response, and there is usually no coordinated provider dispatch carried out by a call centre. Subsequently, there is a lack of emergency medical service (EMS) ambulances to bring patients to a hospital or clinic. Attendance may be further delayed by lack of triage and/or emergency department facilities. Ultimately, there is often a lack of admission facilities such as high or intensive care units (ICU) or early operative care.

All the links in this chain rely heavily on each other and need to be in place in order to be successful. Research conducted at a large Emergency Department in Botswana identified a clear gap. This unpublished prospective observational study observing the outcome of witnessed cardiac arrest revealed that 27% of patients (n=71) regained return of spontaneous circulation. This is up to international standards especially considering there were no cases of shockable rhythm observed. Disappointingly, none of the patients survived to discharge. The main contributing factor was the lack of post cardiac arrest care, as only about half of the patients were admitted to ICU. [8]

Framework proposed by who

Any regional or national approach should be customized and take into consideration the specific burden of disease, gaps in the health care system and resources available. For instance, emergency care in Southern Africa is slowly taking off while in Central Africa there is virtually no emergency care provision. These different areas need different solutions. The ‘WHO emergency care system framework’ is a tool to identify gaps in care delivery and to create context-relevant priority action plans for system improvement. The framework is based on three distinct levels as illustrated in Figure 1. The levels include the scene, transport and the facility. All three have the same key components to function: human resources, protocols and equipment. Some context relevant examples of these components are described below.

Human resources

As scarcity of appropriately skilled providers is an issue, a realistic approach to the attainable level of training as well as task shifting is required. A good example is the introduction of specialist nurses such as Emergency Care Providers (ECPs) in rural Uganda. Since 2009, they have attended to 80,000 patients, which resulted in favourable mortality rates. This suggests that task shifting can be successfully applied to acute care in order to address the shortage of emergency care. [9] In South Africa, there is an overwhelming demand for doctors with skills in emergency care in numbers that the national residency program cannot provide. A Diploma in Primary Emergency Care (DipPEC) was introduced, a one-year core curriculum program, which is now graduating 150-180 candidates per year, providing an immediate solution in a responsible and affordable way. [10] South Africa, Botswana, Rwanda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, Egypt, Sudan, Malawi and Ghana have developed their own emergency medicine residency programs. Local EM specialists are now ready to fill key coordinating roles in EMS and disaster management, guideline development and research as well as teaching. [11]

Context based protocols

Clinical protocols are evidence-based but rely heavily on studies performed in the Western setting. There are strong examples that demonstrate that it is not possible to extrapolate appropriate management to African settings. These include the increased mortality after fluid boluses in children with severe infections found in East Africa as well as the observed increased mortality after an early resuscitation protocol in adults with sepsis in Zambia. [12,13] Both studies contradict current Western guidelines. The African Federation for Emergency Medicine (AFEM) is closing this gap by providing a platform for local researchers to share research in their peer-reviewed journal and by publishing the ‘AFEM Clinical Handbook of Acute and Emergency Care’. Additionally, free online open-access medical education (FoaMED) blogs like #badEM (brave Afri-can discussions in Emergency Medicine, www.badem.co.za) contribute by discussing current issues.

Equipment and it

Resources are required at all levels to function at a minimum level. A call centre with a national alarm number, equipped EMS ambulances, and EDs with equipped shock rooms supported by 24/7 radiology, laboratory and blood bank. Bedside diagnostics in the ED such as ultrasound and portable blood gas machines are quick wins; they make the provider independent, are quickly accessible and generally cheap.

Conclusion

There is still a lot to gain by introducing or improving the emergency care chain in Africa. Looking at Africa’s specific and dynamic burden of disease and its access issues, emergency care is likely to be in high demand. Application of the WHO emergency care system seems to be a useful framework in an African set-ting, especially when scrutinizing specific issues such as weak links in the access chain, realistic training of human resources, and selecting evidence-based pro-tocols applicable to the African setting.

Source: www.who.int/emergencycare/emergencycare_infographic/en

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Emergency and Trauma Care Initiative [internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/emergencycare/global-initiative/en/

- Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), The World Fact Book [internet]. Wash-ington; 2017. Available from: https://www.cia.gov/library/publications/the-world-factbook/rankorder/2102rank.html

- Our World in Data, Burden of Disease [internet], University of Ox-ford/Global Change Data Lab, 2018 Available from: https://ourworldindata.org/burden-of-disease

- World Health Organization (WHO). Disease burden by Cause, Age, Sex, by Country and by Region, 2000-2016. [internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2018. Available from: https://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates/en/index1.html

- U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, The Burden of Non-Communicable Diseases in the Devel-oping World [internet]. Washington; 2015. Available from: https://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/education/curriculum-tools/population-health/baldwin.html

- Norman R, Matzopoulos R, Groenewald P, Bradshaw D. The high burden of injuries in South Africa. Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 2007. 85(9):649-732.

- Haagsma JA, Graetz N, Bolliger I, Naghavi M, Higashi H, Mullany EC et al. The global burden of injury: incidence, mortality, disability-adjusted life years and time trends from the Global Burden of Disease study 2013. Inj Prev. 2016 Feb 1; 22(1):3.

- Lekang K, van Veelen MJ, Cox M. Return of Spontaneous Circulation dur-ing Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR) in Patients with Cardiac Arrest at Princess Marina Hospital Emergency Depart-ment, (PMH ED), Gaboro-ne, unpublished data.

- Chamberlain S, Stolz U, Dreifuss B, Nelson SW, Hammerstedt H, et al. Mortality Related to Acute Illness and Injury in Rural Uganda: Task Shift-ing to Improve Outcomes. PLoS ONE. 2015. 10(4): 20122559.

- The Colleges of Medicine of South Africa (CMSA), Diploma in Primary Emergency Care of the College of Emergency Medicine of South Africa: Dip PEC(SA) [internet]. 2018. Available from: https://www.cmsa.co.za/view_exam.aspx?QualificationID=60

- African Federation of Emergency Medicine (AFEM), Doctors in Emergen-cy Medicine & Leadership Training in Africa [internet]. 2015. Available from: https://afem.africa/project/doctors-in-emergency-medicine-leadership-training-in-africa/

- Maitland K, Kiguli S, Opoka RO et al. Mortal-ity after fluid bolus in African children with severe infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364:2483-2495.

- Andrews B, Semler MW, Muchemwa L, et al. Effect of an Early Resuscita-tion Protocol on In-hospital Mortality Among Adults With Sepsis and Hy-potension: A Ran-domized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 2017;318 (13):1233-1240.