Main content

Case

At a district hospital near Lake Victoria in Tanzania, a 21-year-old primigravida gives birth to a term neonate. The delivery is uncomplicated, but the newborn has an abdominal wall defect with herniated intestinal loops just right of the umbilical cord. In the absence of a membranous sac covering the viscera, the neonate is diagnosed with gastroschisis. The newborn is taken to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). The intestines are covered with sterile gauze and gloves, the stomach is decompressed with a nasogastric tube, intravenous fluids and oxygen are given and a surrogate silo is made with soft saline bags. Referral to a tertiary centre is considered, but the condition of the neonate deteriorates the next day when a hypovolemic shock develops resulting in ischemia of the intestines. In consultation with the family, the neonate is discharged to die at home.

Background

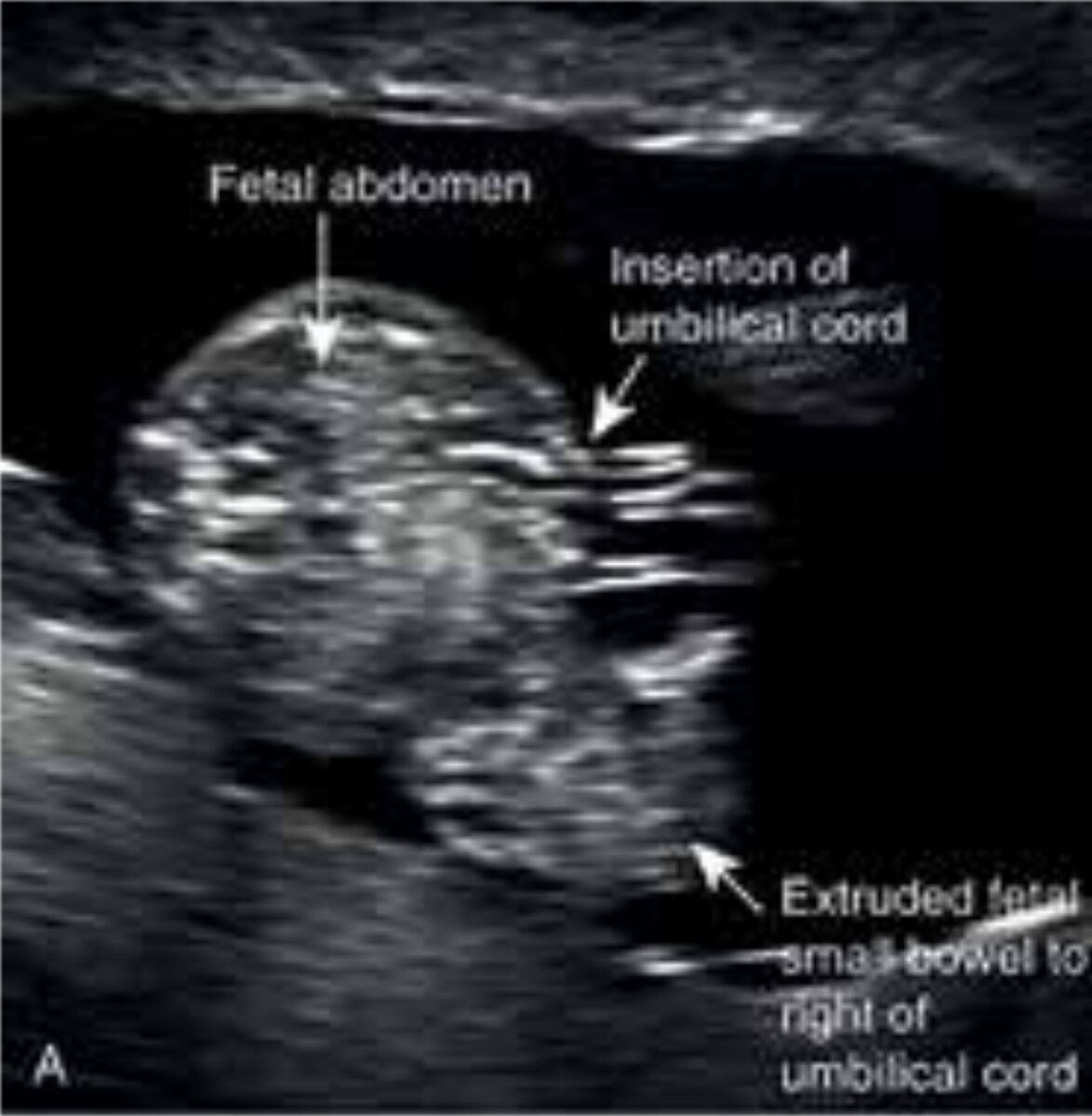

Birth defects are one of the leading causes of death in children under five.[1] Gastroschisis is one of the commonest congenital anomalies. It is a defect of the anterior abdominal wall through which the intestines herniate (Figure 1A and B).[2] Contrary to two other common abdominal wall defects (umbilical hernia and omphalocele), the bowels are not covered by respectively skin or a membranous sac.[2] Gastroschisis has a wide range of clinical presentations, from simple gastroschisis to patients with complex gastroschisis, whereby the defect is complicated by for example intestinal atresia or intestinal necrosis.[3] Gastroschisis is usually isolated and has no known associated chromosomal anomalies.[2] The incidence of gastroschisis is about 1:3000 births and seems to have increased over the last three decades for unknown reasons.[2,4]

Treatment

The main goal of treatment is reduction of the eviscerated contents into the abdominal cavity followed by closure of the defect. The most utilised methods are: operative primary reduction versus staged/gradual reduction over a few days using a silo. A silo is a sterile plastic bag which protects the intestines. The reduction is followed by either sutured immediate closure or sutureless delayed closure. The chosen technique depends on the condition of the intestine and the capacity of the abdominal cavity, as high intra-abdominal pressure might lead to abdominal compartment syndrome.[5] The optimal surgical method for gastroschisis in high-income countries (HICs) remains contro-versial.[4] In low-resource settings, preformed silos may be the most suitable method to treat gastroschisis.[4] This method minimises the risk of abdominal compartment syndrome and the necessity of intensive care. Another advantage of the silos is that a medical officer or specialist nurse can easily apply it at the bedside, preventing a potential delay until surgery in case of primary reduction. A major disadvantage is the cost with a price of US$ 300 per silo.[4] In some middle- and high-income countries, a ten times cheaper alternative has been used: the Alexis Wound Protector and Retractor. However, its effectiveness has not been evaluated yet. Also, improvised silos using sterile urobags and female condoms have been described, with in general poor outcomes.[6]

Outcomes

The outcomes of gastroschisis vary widely globally. In HICs the survival rates have improved from 10% in the 1960s to currently over 95%.[4] This is mostly attributed to antenatal diagnosis, planned delivery, perinatal resuscitation, the availability of NICUs, parenteral nutrition and improvements in surgical techniques.[6] In contrast to HICs where neonates with gastroschisis are almost sure of survival, the opposite is true for neonates in low-income countries: Uganda and Côte d’Ivoire reported survival rates of 0-2%.[4] In middle-income countries, the survival rates are somewhere in-between, with reported survival rates of 20% in Iran, 25% in Nigeria, and 35-71% in South Africa.[4]

State of the art in low-resource settings

Many of the main components of a neonatal surgical care system needed to treat gastroschisis are currently lacking or insufficient in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Even though a majority of pregnant women receive antenatal care, ultrasound is often not included or may not be reliable. Consequently, informing the family on the risks in advance is not possible, and many neonates with gastroschisis are born at home instead of in a health centre. Inappropriate prehospital care and delayed access to healthcare may result in hypothermia, hypovolemia and sepsis, and potentially death. Delays also further complicate the treatment of gastroschisis, as the intestines may become oedematous.

Noteworthy is that in many LMICS there is a stigma towards children with birth defects, and hence they may even not reach healthcare at all. Community education about birth defects and the availability of treatment will be helpful. Neonatal resuscitation may be delayed or ineffective due to a lack of trained professionals. A NICU may not be available. In many low-resource settings, nurses care for many infants, and they may have to focus their care on children who are most likely to survive.[4] Finally, mothers may be insufficiently involved in the care of their child, even though studies have highlighted that this can reduce neonatal mortality.[4] Some of the treatment options require general anaesthesia, for which an educated workforce and specific resources for neonates are needed but are often lacking in low-resource settings. Parental feeding is generally unavailable for neonates, as usually special perinatal nutrition bags for neonates are unavailable. Central intravenous access requires specific training and is often unavailable.

Including gastroschisis in the list of Bellwether procedures could improve the provision of neonatal care (Text box).

Conclusion

There is a large inequality in the outcome of gastroschisis between HICs and LMICs. Several components of a neonatal surgical care system need to be changed or added to improve the survival rates in gastroschisis.

Acknowledges M. van Ingen for contribution to the case description.

| Text box: Bellwether procedures In 2015 The Lancet Commission on Global Surgery proposed laparotomy, caesarean section, and open fracture repair as Bellwether procedures. Bellwether procedures are considered as metric to predict the ability of an institution to perform essential surgical interventions. So, if an institution can perform a laparotomy, it is likely that it can also handle a wide range of general surgery. However, these three mentioned procedures might not be useful predictors for the ability to carry out neonatal and children’s surgical care. Ford et al. suggested gastroschisis as a Bellwether surgical procedure for neonatal care.[7] Surgical treatment of gastroschisis is considered especially useful as a Bellwether procedure as it requires all the components of a neonatal surgical care system.[4] |

References

- GBD 2015 Child Mortality Collaborators. Global, regional, national, and selected subnational levels of stillbirths, neonatal, infant, and under-5 mortality, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2016 Oct 8;388(10053):1725:74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31575-6

- Schoenwolf GC, Bleyl SB, Brauer PR, et al. Larsen’s Human Embryology. 5th ed. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2014. 576 р.

- Laje P, Fraga MV, Peranteau WH, et al. Complex gastroschisis: clinical spectrum and neonatal outcomes at a referral center. J Pediatr Surg. 2018 Oct;53(10):1904-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg. 2018.03.011

- Wright NJ, Sekabira J, Ade-Ajayi N. Care of infants with gastroschisis in low-resource settings. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2018 Oct;27(5):321-6. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg. 2018.08.004

- Petrosyan M, Sandler AD. Closure methods in gastroschisis. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2018 Oct;27(5):304-8. doi: 10.1053/j.sempedsurg. 2018.08.009

- Oyinloye AO, Abubakar AM, Wabada S, et al. Challenges and Outcomes of Management of Gastroschisis at a Tertiary Institution in North-Eastern Nigeria. Front Surg. 2020;7:8.

- Ford K, Poenaru D, Moulot O, et al. Gastroschisis: Bellwether for neonatal surgery capacity in low-resource settings? J Pediatr Surg. 2016;51(8):1262-7