Main content

Access to essential medicines is a crucial condition for addressing the most important global health challenges, such as child survival, maternal mortality, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, malaria and the growing global epidemic of non-communicable diseases. Access to essential medicines is therefore also widely recognized as part of the progressive realization of human rights. The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights of 1966, now ratified by over 160 countries, specifically mentions access to health care goods and services as part of the fundamental right to the highest attainable standard of health (i.e. the right to health). (1) The authoritative General Comment 14 of the Commission on Economic, Cultural and Social Rights of 2000 specifies that the right to goods and services includes essential medicines ‘as defined by the WHO Action Programme on Essential Medicines’. (2) Numerous national court cases have further confirmed these rights for individual patients or patient groups. (3)

The first World Health Organization (WHO) Model List of Essential Medicines was issued in 1977. However, the international essential medicines movement really started in 1985. In that year, around 200 government officials and experts from over 50 countries met in Nairobi to discuss an action plan to improve the use of medicines worldwide. According to Halfdan Mahler, director-general of the WHO at the time, the meeting was ‘a historical landmark in the evolution of the action required to ensure that drugs are used more rationally throughout the world’. This remains the only global conference to date where government officials and independent experts were specifically convened to discuss essential medicines policies.

The results of the Nairobi conference were adopted by the World Health Assembly in 1986. This triggered a series of actions to improve access to and use of medicines that are still relevant today: (1) international guidelines to develop national pharmaceutical policies, (2) programmes to strengthen regulatory authorities, (3) teaching materials for health care professionals, (4) good procurement and distribution practices, and (5) global standards for information about medicines. By the turn of the century, 156 countries had defined a national list of essential medicines. After 2000, the concept of essential medicines also proved to be a critical element towards achieving the health-related Millennium Development Goals. Medicines and vaccines have been key to the eradication of diseases (small pox and polio), the mitigation of pandemics (HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria) and the reduction of maternal and child mortality.

Future directions

Essential medicines will remain important in the future as well. The discussions on the post-2015 development goals and the 30th anniversary of the Nairobi conference in November 2015 provide an opportunity to raise awareness of the global relevance of the essential medicine concept, and to update the needs for further operational research to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of essential medicines policies and programmes.

It is against this background that in 2014 The Lancet established a Lancet Commission on Essential Medicine Policies(4) to take stock of what has been learned over the last 30 years and to use new insights for the effective implementation of the new Sustainable Development Goals (SDG). The Commission report, which is expected in 2016, will use as its framework the new SDG and its medicine-related targets (See box).

| Medicine-related sustainable development goals (draft May 2015) SDG 3.8: Achieve universal health coverage (UHC), including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health care services, and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all. SDG 3.b: Support research and development of vaccines and medicines for the communicable and non-communicable diseases that primarily affect developing countries, provide access to affordable essential medicines and vaccines, in accordance with the Doha Declaration which affirms the right of developing countries to use to the full the provisions in the TRIPS agreement regarding flexibilities to protect public health and, in particular, provide access to medicines for all. |

These two SDGs reflect the two most important challenges in national medicine policies: (1) to ensure equitable access to essential medicines as part of universal health care and the fulfilment of the ‘right to health; and (2) to promote research and development of missing essential medicines and ensure their availability (physical and financial) to all who need them.

Equitable access to basic essential medicines

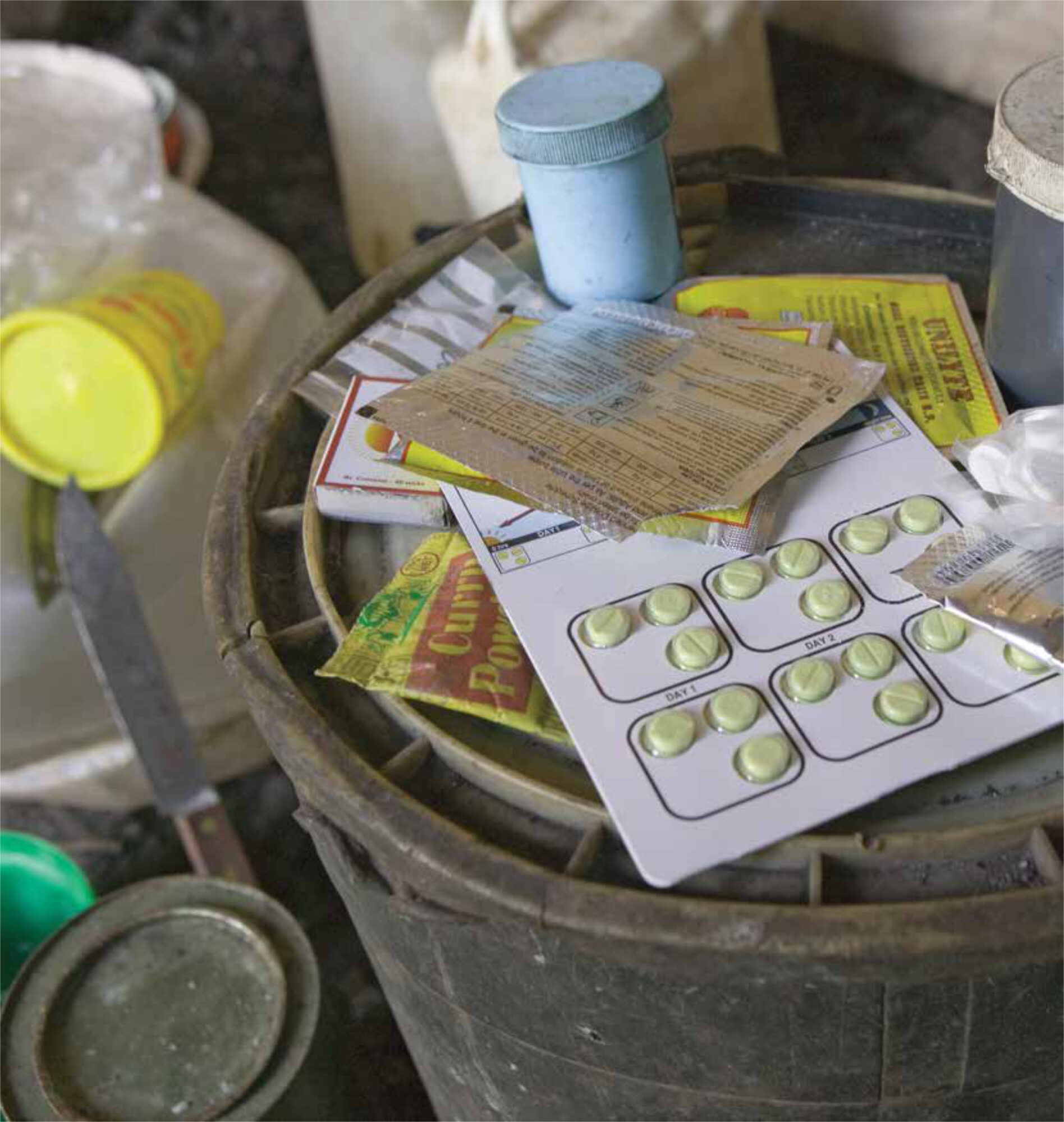

Exact estimates are difficult, but the best guesses remain that in many very low and low income countries about a third of the population has no regular access to a basic range of affordable essential medicines of assured quality. In some areas, this figure can be as much as half the population. Indeed, a house-hold survey in Uganda showed that a third of the people interviewed had never been able to get the medicines they were prescribed the last time they consulted a health worker. (5)

Very detailed WHO Service Availability and Readiness Assessments surveys have also shown that a large proportion of rural clinics miss several key medicines for maternal health, such as oral and injectable contraceptives, oxytocin, misoprostol and magnesium sulphate. It is clear that, without such medicines, reproductive care is simply not possible. These and other data support earlier estimates that between one and two billion people have no access to basic essential medicines yet. It should be mentioned here that only one-third of the 1.4 billion global poor live in least-developed countries; two-thirds are now found in the lower economic strata of middle-income countries. Inequity between countries is gradually being replaced by inequity within countries.

Equitable access to new essential medicines

New essential medicines are expensive, as the case of antiretroviral medicines (ARVs) has shown. Originally they were priced at over USD 10,000 per person per year. WHO classification as an essential medicine in 2002, international advocacy and action by NGOs, generic production of fixed-dose combinations in India, the WHO/UN prequalification programme, and large-scale public funding through the Global Fund, the United States President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and UNITAID have achieved a 99% price reduction. The current first-level regimens now cost less than USD 80 per person per year. This was not the result of free market forces but of concerted international action. The 100-fold price differential between originator price and final generic price is in line with a similar ratio that has been in existence for 40 years for standard childhood vaccines and oral contraceptives. However, the situation is very different for second-line ARVs and new medicines for tuberculosis. Here the prices can still be very high, especially in middle-income countries, because of new patent legislation demanded through the World Trade Organization and bilateral trade agreements like the TRIPS Agreement. Several new essential medicines are now where the first-line ARVs were in 2002. In April of this year, the WHO added 20 medicines for common and treatable cancers to the latest Model List of Essential Medicines. Many of these medicines are still under patent and most will be out of reach for most patients in low- and middle-income countries. Yet this listing is a very important first step, as it implies that these medicines will now have to be made affordable to all who need them.

Conclusion

As demonstrated by the case of ARVs, free market forces will never achieve universal access to medicine for the poor. Concerted government action is needed to make all medicines from the latest Model List of Essential Medicines available for all patients who need them, at a price the patients and the community can afford. The practical application of human rights is increasingly being used by governments as a framework for promoting equity and achieving the new sustainable development goals.

References

- International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Available at http://www.ohchr.org/EN/ProfessionalInterest/Pages/CESCR.aspx (accessed 9 July 2015)

- UN Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, 2000. General Comment no. 14. Available at: http://www.nesri.org/resources/general-comment-no-14-the-right-to-the-highest-attainable-standard-of-health (accessed 9 July 2015)

- Hogerzeil HV, Samson M, Vidal Casanovas J, Rahmani I. Is access to essential medicines as part of the fulfillment of the right to health enforceable through the courts? Lancet 2006; 368: 305-311

- A new Lancet Commission on Essential Medicines. Editorial. Lancet 2014; 384: 1642

- Access to and use of medicines by households in Uganda. Uganda: Ministry of Health, 2008